Intel’s Immiseration

The long, seemingly inevitable decline of an icon

How did you go bankrupt?

Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

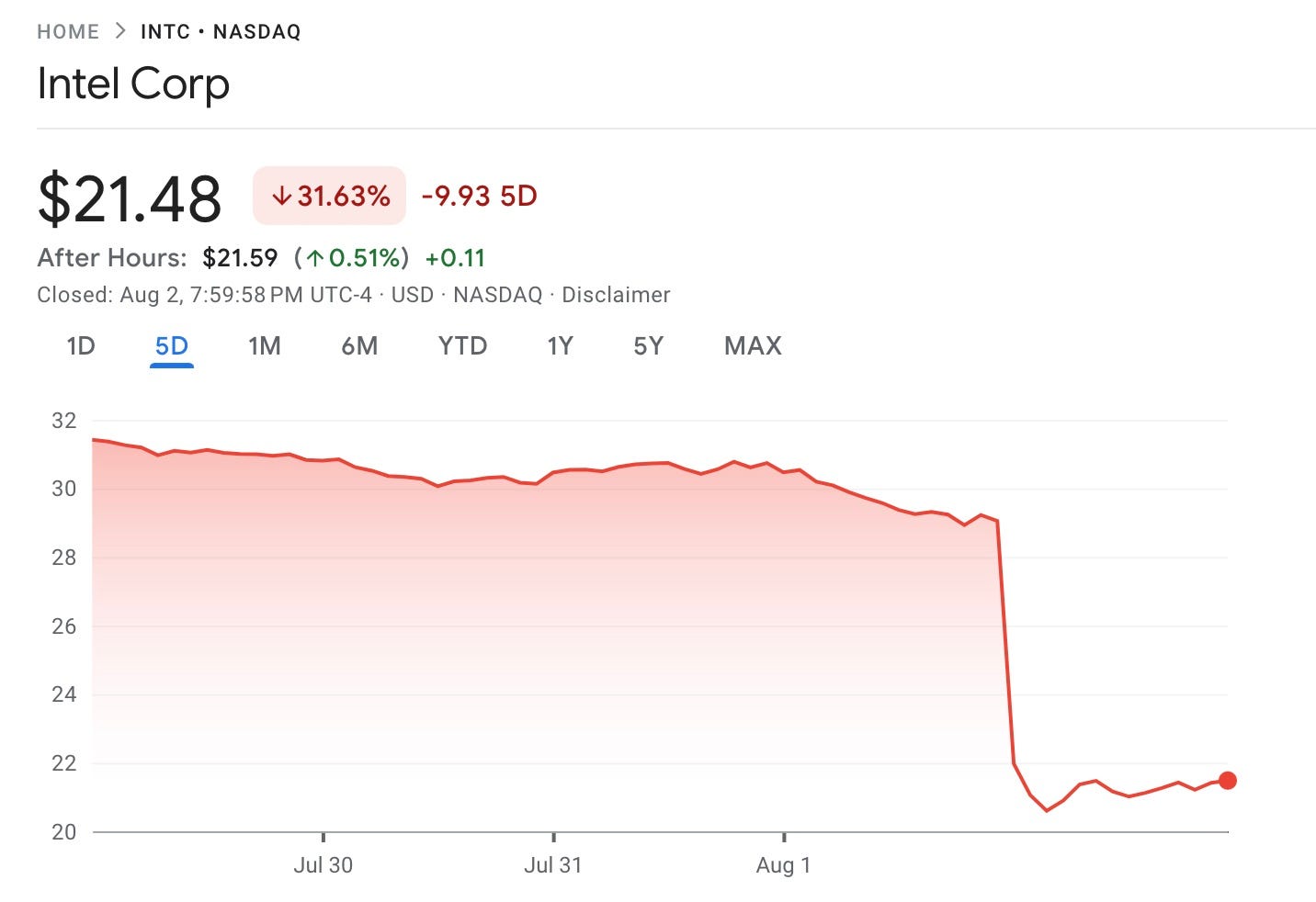

Last Thursday was a historically bad day for Intel’s share price.

This fall left Intel with a market capitalization lower than Arm.

The proximate cause was Intel’s Q2 2024 results.

I’m not sure ‘Highlights’ is quite the right word here.

Revenue for the quarter was a third lower than in the corresponding quarter three years ago.

The Q3 2024 outlook had revenue, gross margin, and EPS all down.

Ben Bajarin on the excellent Circuit podcast caught the mood:

The numbers were bad. When I say disappointing, I mean this at an emotional level as well. I really believed things were on a steady, sustainable path to recovery. I thought after we went through the bottom last year, this time we talked about them being at an all-time low for gross margins … I thought this was going to be pretty consistent, like it’s never going to be great, but it’s not going to be that bad again. And it’s that bad again, if not worse …

Meanwhile, Intel’s highlighted ‘good news’ on products was underwhelming. No amount of AI magic dust can disguise the fact that this is about laptop SoCs a market in which Intel faces new and vigorous competition.

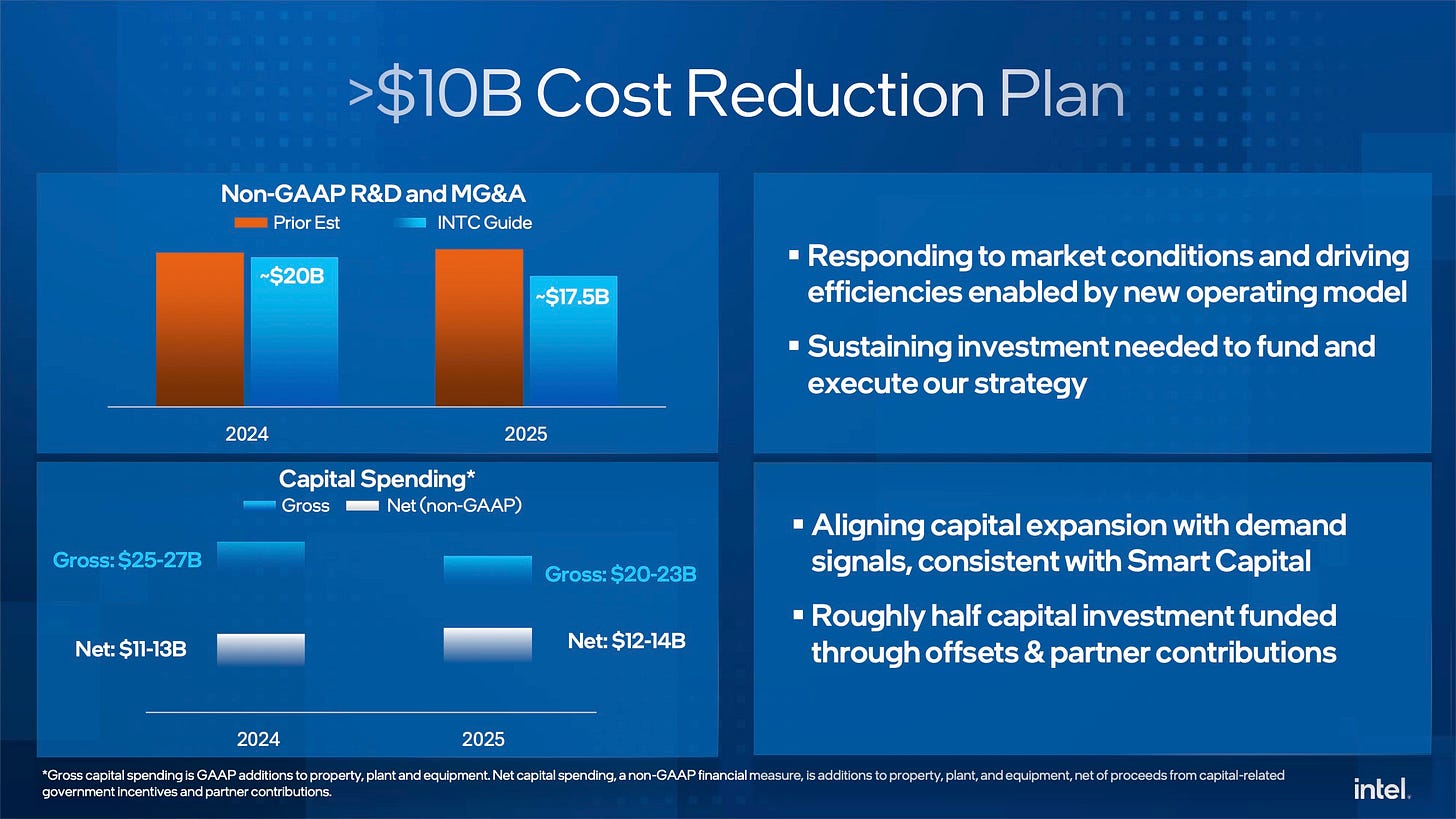

Intel’s management reached for the ‘cost-cutting’ lever with a plan to cut the company’s headcount by as much as 15%.

I know that I have many readers who work at Intel. I’m truly sorry for anyone who is affected by these job losses.

An internal memo from CEO Pat Gelsinger summed up how tough things are:

I have no illusions that the path in front of us will be easy. You shouldn’t either. This is a tough day for all of us and there will be more tough days ahead.

Complicating the picture is Intel’s status as the last US-controlled at or close to leading-edge logic maker and the recipient of billions of dollars from the CHIPS and Science Act. While it retains this status then it’s impossible to see Intel following Hemingway’s character into bankruptcy. The importance of this status means that we can perhaps see Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger’s focus on ‘5 nodes in 4 years’ as being about the politics of retaining this status, alongside its commercial importance.

This fell on deaf ears at the WSJ though:

Intel has been awarded $8.5 billion in grants and up to $11 billion in loans to expand U.S. manufacturing production.

While chasing subsidies, Intel missed out on the AI boom, which has cost it dearly as competitors surge ahead. Now it’s playing catch-up. When government steers capital, companies sometimes get distracted and drive into a cul-de-sac.

If some reacted with shock at these results, the response from others was more optimistic. A few quotes from a recent post from popular economics blogger Noah Smith capture this reaction well:

And Intel’s job cuts, painful as they are for the workers affected, are a cost-cutting move that will free up more cash to invest in the company’s recovery plan. Whether that plan will succeed isn’t clear yet, but if you were going to turn a company like Intel around, this is probably how you’d start.

Meanwhile, Intel’s turnaround plans — including a foundry business like TSMC’s and investments in AI chips — are still in the early stages. One reason profits have fallen at Intel is that it’s investing heavily.

Smith’s defense against the criticism of wasted dollars and the need for patience might be reasonable, but I’m not sure that presenting this as the ‘start’ and ‘early stages’ of a turnaround plan is credible.

Gelsinger started his tenure as Intel CEO in February 2021. Generally, a company that’s three and a half years into a turn-around, needs more to show than a partial fix to manufacturing issues to convince investors that the plan is on track.

What makes all this worse is that the ‘gradually’ in Hemingway’s quote we started this post seems entirely apt. This isn’t a sudden fall from grace. I’d argue that there has been a sense of inevitability about Intel’s trajectory for at least a decade.

Tracing the Decline

Before revisiting the roots of Intel’s decline, let’s set aside some commonly cited candidates that I don’t think can be blamed as the primary cause of Intel’s woes.

There have been some important key failures. In particular the delays in adopting EUV lithography and the persistent problems with the roll-out of its 10nm process node. This led to Intel ceding process leadership to TSMC.

There have been clear one-off M&A missteps - the strange acquisition of McAfee being the most glaring. Although some have been expensive the worst that can be said of them is that they were a distraction and symptomatic of a lack of focus.

Equally, a simplistic placing of blame on ‘bean counters’ doesn’t seem right. Intel has had a CEO with a finance background only during Bob Swan’s brief tenure which ended with Pat Gelsinger’s return to the company in 2021.

Rather, the real root of Intel’s problems lies in its inability to expand beyond the ‘moat’ of its x86 desktop and server processor business.

Readers will remember that I’ve written about this before, in ‘The Paradox of x86’:

From this earlier post:

… the moat provided by x86 erected multiple barriers to breaking away from the x86 desktop / server core of Intel’s business.

First, in 2006 Intel’s x86 business was hugely profitable. Why would the company add any risk to that business? In particular why would the company:

Take resources from x86 to focus on lower return projects?

Open up its market-leading fabs to architectures that might ultimately challenge x86 on the desktop and on servers?

…

Second, Intel’s desktop and server x86 business was hugely profitable. Why dilute that business making SoCs using someone else’s processor architecture, a much lower margin business with a smaller moat?

This ‘moat’ was one factor in Intel's missing the smartphone System-on-Chip market:

Intel passed on making the System on Chip for Apple’s new iPhone, launched at the start of 2007. Instead Apple used an Arm designed processor in an SoC built by Samsung.

Too late Intel realised the mistake. Over ten billion of dollars were spent on an, ultimately futile, attempt to gain a foothold in the smartphone SoC market. Intel finally gave up in 2016, ceding the market to Arm processors in SoCs made by Samsung and TSMC.

Today, Apple is TSMC’s biggest customer, and smartphones make up over 40% of the Taiwanese company’s revenues.

This ‘miss’ has hung over the company ever since.

And it’s left a, still unanswered, question. Intel couldn't break into smartphone SoCs with clear process leadership and the financial strength to invest heavily. Why should it be able to break into other competitive markets today when it no longer has those advantages?

I’ll leave it to others to try to answer this question - please see some of the links below discussing Intel’s recent results.

The importance of the story of Intel’s smartphone miss though means that I believe it’s worth revisiting in more detail and we’ll do so in the next post.

Oversimplifying dramatically, my concern about Intel's future began in 2005 when a sales and marketing person, Otellini, became CEO. But their problems began earlier than that as the brilliant founders aged, lost interest in the complexities of the total business, then aged out of all participation. Hubris defeated their best intentions, first by moving away from x86 with Itanium then not moving away from x86 with mobile.

where "like" means thanks for summarizing. I listened to Ben and Jay's discussion on the Circuit podcast as well. Like them, I'm wondering why INTC didn't cut the dividend earlier, and do layoffs earlier (if they truly were needed), when it really had carte blanche to. Rephrased, another shoe dropped, and I'm wondering if there will yet be more.

I did a media interview with a reporter in the Oregon area today, who was wondering about local employment impact (Intel is about 4% of state employment), and if it was indicative of more layoffs coming in semis. My comment was this announcement was more about Intel than about the semiconductor industry.