Intel's Larabee Legacy

Intel's long series of unforced errors on graphics and vector instructions

Everyone is dunking on Intel (yet again) and I really didn’t want to join in …

However, with the launch of Intel’s latest mobile design - known as Panther Lake - one feature (or rather lack of a feature) jumped out and had me retracing Intel’s history to understand how historic mistakes can continue to hinder a company for decades.

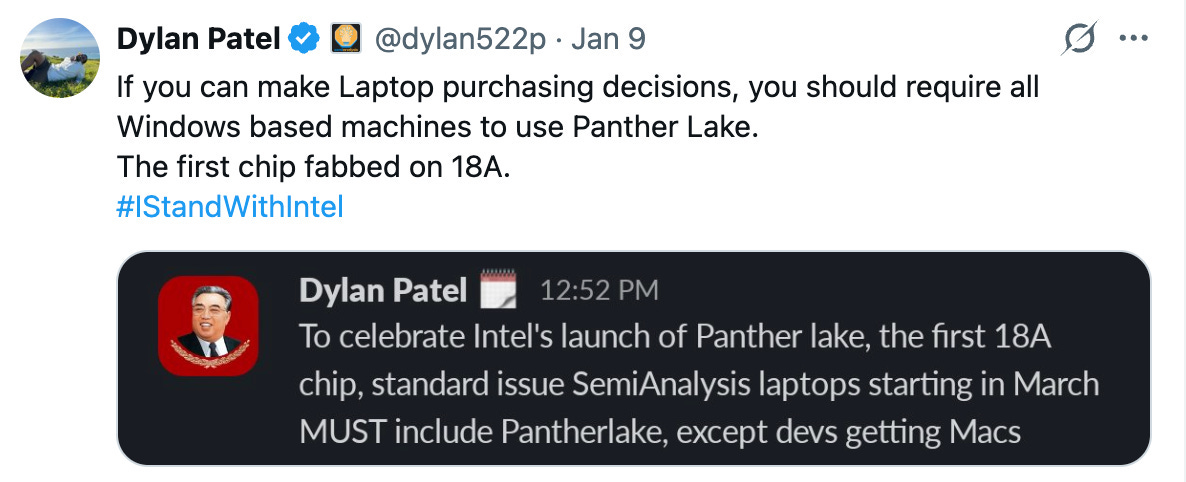

Panther Lake has certain highly respected analysts quite excited.

And Panther Lake is exciting on many fronts.

Sadly, though, I won’t be joining the SemiAnalysis team, for reasons I’ll explain later.

Our story - in this part free and part paid post - starts with Intel’s former CEO, Pat Gelsinger:

Soon after Pat Gelsinger’s second departure from Intel, Bryan Cantrill on the Oxide podcast highlighted a section of Gelsinger’s Oral History, given to the Computer History Museum in 2019. Gelsinger discusses a project that he’d backed at Intel shortly before leaving for the first time in 2010.

In a, nearly four hour long, interview Gelsinger makes a strong claim about one particular Intel project:

We were in the right space, and had Intel stayed with it the world of machine learning, AI, Nvidia would be a fourth the size they are today as a company …

For context, the interview was given in March 2019, whilst Gelsinger was still CEO of VMWare and Nvidia had a (stock split adjusted) share price of less than $5 (compared to more than $180 at the time of writing this post) and a market cap of around $100bn (compared to more than $4.5 trillion today).

The name of that Intel project? Larrabee.

In the podcast Cantrill has a strong reaction to Gelsinger’s claims.

I was washing the dishes as I was listening to this, and it stopped me in my tracks: I turned off the faucet, dried my hands, and backed up the recording. Had I heard correctly?!

The reason for this response?

If one wanted to make this eyewatering claim, it must be loaded with riders and caveats: it must acknowledge that Larrabee itself was an unusable disaster; that NVIDIA had an indisputable lead, even in 2009; that for Intel to dominate NVIDIA it would have required conjuring software expertise and focus with which Intel has famously struggled; that Intel had no pattern for sustained success out of x86.

Cantrill was not impressed!

On the one hand, there were enough qualifiers from Gelsinger to soften this claim a little (and at least some passing respect for NVIDIA’s Jenson Huang and Bill Dally), but on the other… yes, he actually claimed that NVIDIA had his departure from Intel to thank for (checks transcript) three quarters of its size.

And Cantrill wasn’t the only one to be surprised by these claims:

I think even the interviewers were a little taken aback, and asked the question directly: “Do you think that it was in part that you weren’t there to drive [Larrabee] forward that they decided to withdraw from that?” Gelsinger’s response: “Yeah, I’ll say that very directly.”

Here is the video of the Oral History if you want to hear Gelsinger himself:

Cantrill then goes on to use this as part of his case that, as the title of a blog post makes clear Gelsinger was wrong for Intel.

I have great reverence for Intel and its extraordinary history, and I would never count them out (the resurrection of a clinically-dead AMD shows what is possible!), but I also won’t be integrating with any of their technology until their acute cultural issues are addressed. With regard to these cultural issues (and his other strengths aside), Pat Gelsinger was indisputably wrong for Intel.

The world has moved on since Gelsinger’s departure and in Lip-Bu Tan has a very different leader, but it turns out that Larabee arguably casts a long shadow over Intel’s history and decline over the last decade and a half.

But what was Larabee?

In short, it was an attempt to build a graphics architecture based on Intel’s x86 CPU designs.

From the perspective of 2026, Larabee sounds a little bit, well, mad. Surely a GPU based on x86 was never going to be able to compete with the latest offerings from Nvidia and others? x86 famously has lots of baggage and competing with the latest dedicated GPU offerings from Nvidia and AMD would give Intel a mountain to climb.

I’ve written before about how x86 has turned from a ‘moat’ to a ‘prison’ for Intel.

And so it turned out: Larabee proved to be uncompetitive. Its development got as far as creating a (still working) prototype which made it into the wild and is now a collectors item:

In order to be even remotely competitive though Larabee needed to add some new instructions, known as Larabee New Instructions (LRBni), to x86. LRBni added new 512-bit vector instructions as this post from Michael Abrash, who was central to their development, sets out:

LRBni adds two sorts of registers to the x86 architectural state.

There are 32 new 512-bit vector registers, v0-v31, and 8 new 16-bit vector mask registers, k0-k7. … LRBni vector instructions are either 16-wide or 8-wide, so a vector register can be operated on by a single LRBni instruction as 16 float32s, 16 int32s, 8 float64s, or 8 int64s … with all elements operated on in parallel.

LRBni vector instructions are also ternary; that is, they involve three vector registers, of which typically two are inputs and the third the output. This eliminates the need for most move instructions; such instructions are not a significant burden on out-of-order cores, which can schedule them in parallel with other work, but they would slow Larrabee's in-order pipeline considerably.

Leaving aside whether an x86 based GPU was a good idea in the first place, the project itself has been widely recognised as a disaster. This post from 2009 lays out lots of the gory detail:

… as the time went by, we received bits and pieces with more worrying content. Back in 2007, when Larrabee started to take physical shape, we heard some very worrying statements coming from the people that were coming and going from the team. Most worrisome was the issue with the memory controller – “people involved in designing high performance memory controllers don’t even understand the basic concepts of pipelining and they don’t understand how to read a memory spec. It is completely ridiculous.”

With a 2009 assessment of how much Larabee cost

The real question of did AMD overpay for ATI Technologies Inc. can only be concluded once that the cost of Intel building Larrabee on its own becomes a matter of public knowledge. Over the past few years, we heard several different calculations with almost each and every one being well over a billion dollars. Worst case that we heard was “we burned through three billion USD”, but that belongs in the speculation category. Do bear in mind that the figures aren’t coming from the bean counters and that the cost of slippage cannot be calculated yet.

The Larabee project was finally brought to an end in May 2010.

For balance here is a more positive assessment from a member of the Larabee team that focuses on the objectives of the project:

… Larrabee was never primarily a graphics card. If Intel had wanted a kick-ass graphics card, they already had a very good graphics team begging to be allowed to build a nice big fat hot discrete GPU - and the Gen architecture is such that they'd build a great one, too. But Intel management didn't want one, and still doesn't. But if we were going to build Larrabee anyway, they wanted us to cover that market as well.

But killing products has consequences.

Intel really needed a discrete GPU to compete with Nvidia and AMD. The end of Larabee meant it was left without one.

And with the benefit of hindsight, the failure was even more damaging than was realised at the time. Intel had no competitive GPU that could participate in AI boom of the 2020s.

Intel’s Trust Issues

And the impact of Larabee’s failure is arguably even more far reaching with consequences that are still affecting Intel today.