Obsolescence

How long will your chips last for? It's a complex multi-trillion dollar question.

I have a confession: I like shiny new technology as much as, if not more than, anyone else. When the latest version of MacOS was released a few weeks ago, I cast caution aside and rushed to update my Mac. So far MacOS 26 Tahoe has rewarded my confidence. I’m seemingly one of a tiny minority who like the new icons and elegantly rounded window corners.

But this update was somewhat bittersweet. Apple says that this is the last time I’ll be able to experience the warm glow of being an early adopter on this machine. Because my trusty MacBook Pro is, shockingly, now five years old. Except, I shouldn’t be shocked at all. My machine has an Intel processor, long since abandoned by Apple in favour of their own Arm-based Apple Silicon designs. When I bought my Mac back in 2020, after Apple Silicon was announced, I wanted a machine with Intel’s AVX512 instructions for a particular project, and I knew that the price I would have to pay, along with much worse battery life, was that it would be superceded sooner rather than later.

All is not lost though. Apple will certainly provide security updates for a few more years. Mac OS Monterey, which runs on laptops from as far back as 2015, is still receiving these updates. With luck my machine should still be a viable workhorse for another half-decade.

And, on reflection, close to a decade of use is quite remarkable and unusual. A budget Android phone, for example, might receive a year or two of updates. I should probably be happy that my machine will last so long.

At the time I was updating my Mac, I happened across an article in the Economist that examined how tech firms are accounting for their stupendous investment in ‘AI datacenters’.

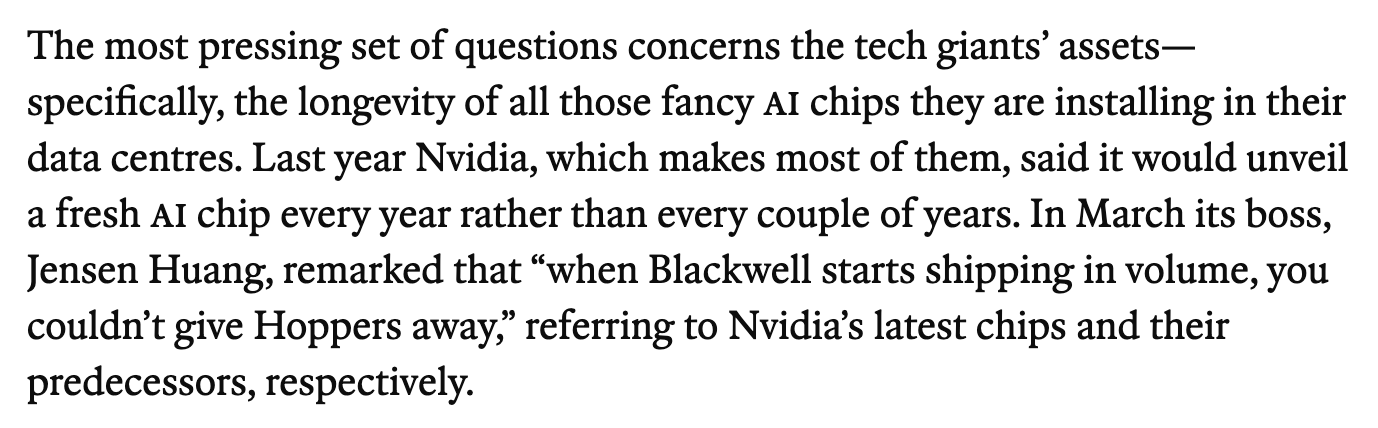

As might be expected, when firms are spending, individually hundreds of billions, and collectively trillions of dollars, there is strong interest in how that ‘capital investment’ is affecting their profits and balance sheets. Questions are being asked, and as the Economist says:

Jensen was joking, of course. I certainly hope so.

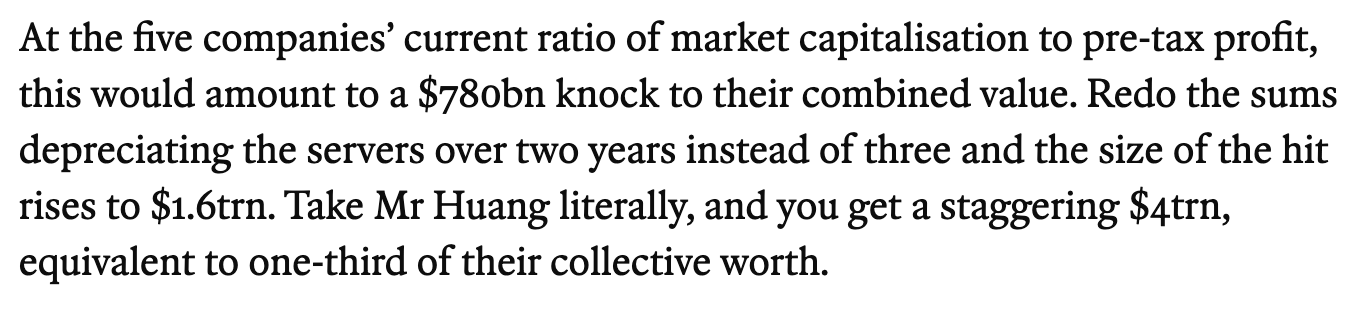

As the Economist describes, the ‘AI hyperscalers’ typically assume that their chips will remain in use for between four and six years. Others believe that a lifetime of two to three years is more realistic. That gap has serious financial implications. The Economist starts by considering the potential implications of a three-year life-span for these chips on the five leading hyperscalers:

Given the importance of this investment in data-centers for the US and wider world economies, there could be an awful lot resting on the longevity of Nvidia’s chips.

So it might be a good time to talk about obsolescence, a topic that gets discussed less than perhaps it deserves. In the rest of this post we’ll examine the factors that lead to hardware becoming obsolete and what we can learn from this.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Chip Letter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.