Qualcomm RISCs, Arm Pulls: The Legal Battle for the Future of Client Computing

What happens when a gladiator takes on the “Warren Buffett of Japan”?

“You have to bet the company. Especially right now, it’s like being in the gladiator business: you go in, you prepare, you go to the Colosseum …”

Cristiano Amon, Qualcomm CEO, Jan 2022 via Financial Times

Who controls an Instruction Set Architecture? The answer may be less obvious than it first seems.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Intel developed and seemingly controlled the architecture we now know as x86. Except Intel didn’t fully control x86. It had granted ‘second-source’ licenses to several firms to build 8086 and 80286 compatible CPUs. When Intel denied ‘second-source’ rights to other firms for the 80386 some of those firms, most importantly AMD, reverse-engineered the new design and sold their own versions of the 80386.

By the late 1990s and several legal disputes later, AMD was firmly established as an alternative vendor of x86 designs. So firmly established that when Intel neglected to extend x86 to a 64-bit address space, AMD’s 64-bit extension (AMD64) quickly became the standard and was soon adopted by Intel (although, of course, named Intel64 in Intel documentation).

On 15 October 2024, the two firms announced the formation of the x86 Ecosystem Advisory Group recognizing at last that neither firm fully controlled the x86 platform. In the press release, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger commented:

“We proudly stand together with AMD and the founding members of this advisory group, as we ignite the future of compute, and we deeply appreciate the support of so many industry leaders.”

And other firms were able to take advantage of Intel’s lack of complete control over x86. As we saw in ‘Intel vs NEC: the case of the V20’s Microcode’, NEC won a court case in 1984 that enabled it to make 8086 compatible CPUs without paying license fees to Intel.

This brings us to the subject of this post, the ongoing legal battle between Arm and Qualcomm.

Arm Cancels Qualcomm’s License

On 23 October 2024, a little more than a week after the Intel and AMD announcement, news broke on Bloomberg of the latest development in the long-running Qualcomm vs. Arm legal dispute:

Arm Holdings Plc is canceling a license that allowed longtime partner Qualcomm Inc. to use Arm intellectual property to design chips, escalating a legal dispute over vital smartphone technology.

Arm, based in the UK, has given Qualcomm a mandated 60-day notice of the cancellation of their so-called architectural license agreement, according to a document seen by Bloomberg.

Both companies issued statements shortly afterward. From Qualcomm

"This is more of the same from Arm – more unfounded threats designed to strongarm a longtime partner, interfere with our performance-leading CPUs, and increase royalty rates regardless of the broad rights under our architecture license."

"With a trial fast approaching in December, Arm’s desperate ploy appears to be an attempt to disrupt the legal process, and its claim for termination is completely baseless. We are confident that Qualcomm’s rights under its agreement with Arm will be affirmed. Arm’s anticompetitive conduct will not be tolerated.”

and from Arm:

“Following Qualcomm's repeated material breaches of Arm's license agreement, Arm is left with no choice but to take formal action requiring Qualcomm to remedy its breach or face termination of the agreement. This is necessary to protect the unparalleled ecosystem that Arm and its highly valued partners have built over more than 30 years. Arm is fully prepared for the trial in December and remains confident that the Court will find in Arm's favor.”

Strong words from both firms!

This shouldn’t be a surprise though. Arm threatened to do this back in Nov 2022 as reported by

.“Qualcomm is materially breaching its [Architecture License Agreement], giving Arm the right to terminate, and the Qualcomm [Architecture License Agreement] does not provide a license for or right to continue development of the Nuvia technology.”

It’s certainly a bold move. Qualcomm is a longstanding Arm partner and is believed to be Arm’s biggest customer by revenue.

Unsurprisingly, there have been some strong reactions to Arm’s move. Irrational Analysis called it Arm’s Chernobyl Moment:

Canceling the architectural license of your largest customer is extraordinarily destructive. Batshit insane.

Digits to Dollars was more measured but still perturbed:

And this raises a more serious concern than any short-term impact of a license getting canceled. Arm also has plenty of smart lawyers who recognize the flimsy nature of this threat. …

Our concern is simply that this lawsuit risks hurting both companies at a time when both should have higher priorities.

Two main themes have featured in some commentary in this news, namely that:

This is a highly self-destructive attack by Arm on its ecosystem;

It will give an enormous boost to RISC-V.

Arm isn’t a company that is generally known for its ‘batshit insane’ moves. So we’ll spend the rest of this post trying to understand the case, its implications, and the motivations of Qualcomm and Arm.

Note that this is a part-free and part-paid post. The basics of the case are set out in the free part with further analysis for paid subscribers.

Two initial points. First, this is hugely important. Bloomberg comments that:

Qualcomm sells hundreds of millions of processors annually — technology used in the majority of Android smartphones. If the cancellation takes effect, the company might have to stop selling products that account for much of its roughly $39 billion in revenue, or face claims for massive damages. …

As we’ll see in a moment the case will also have implications well beyond the futures of the two companies directly involved. It could have a huge impact on the future of computing on smartphones, laptops, and automobiles.

The result could decide who controls the hardware that powers a significant portion of client computing for many years ahead. There is a lot at stake.

Second, I have no idea who will win. The outcome will depend, in part, on material that has not been publicly disclosed, the strength of the arguments made by each side’s lawyers, and the whims of the jury.

Before we start, this isn’t investment or legal advice. I don’t know the outcome of this court case and nothing in this post should be interpreted as such.

Qualcomm vs Arm: A Timeline of the Dispute

We’ll start with a timeline of the legal dispute between Qualcomm and Arm. It begins with Nuvia.

Feb 2019: Nuvia is founded by Gerard Williams III (CEO), Manu Gulati (SVP of Silicon Engineering) and John Bruno (SVP of System Engineering)

Williams was formerly of Apple (where he led the design of Apple’s highly regarded Arm processors for almost a decade), Arm (where he was a Fellow), TI, and Intel. Gulati and Bruno had previously worked at Google, Apple, AMD, and other firms.

Nov 2019: Nuvia announces $53m funding to create Arm data-center CPUs

Sept 2020: Nuvia raises $240m in further funding

Jan 2021: Qualcomm agrees to acquire Nuvia for around $1.4bn. Notably, Qualcomm’s announcement of the deal had endorsements from a long list of partners whilst failing to mention Arm. It later emerges that Qualcomm and Nuvia had failed to notify Arm - a key supplier of the technology used by Nuvia - in advance of the deal.

Aug 2022: Arm sues Qualcomm alleging that:

… Qualcomm caused Nuvia to breach its Arm licenses, leading Arm to terminate those licenses, in turn requiring Qualcomm and Nuvia to stop using and destroy any Arm-based technology developed under the licenses. Undeterred, Qualcomm and Nuvia have continued working on Nuvia’s implementation of Arm architecture in violation of Arm’s rights as the creator and licensor of its technology. Further, Qualcomm’s conduct indicates that it has already and further intends to use Arm’s trademarks to advertise and sell the resulting products in the United States, even though those products are unlicensed.

Sept 2022: Qualcomm responds to Arm’s lawsuit:

“ARM’s position is a threat to the industry generally. Unless this Court rejects

ARM’s arguments, ARM’s extreme position could be weaponized against all of its licensees, allowing ARM to claim ownership over all its licensees’ innovations.”

“As this litigation will show, Qualcomm and NUVIA have not violated NUVIA’s

ALA or any other license agreement. Nor have they misused ARM’s trademarks.”

Oct 2023: Qualcomm announces the Snapdragon Elite X series of laptop ‘System on Chips’ with Qualcomm’s Oryon Arm-compatible processor cores built using Nuvia technology. Quoting Anandtech:

“Oryon is essentially a third-party acquisition by Qualcomm. The CPU core began life as “Phoenix”, and was being developed by the chip startup NUVIA.

…And while Qualcomm isn’t focusing too much on Oryon’s roots, it’s clear that the first-generation architecture – employing Arm’s v8.7-A ISA – is still deeply rooted in those initial Phoenix designs.”

Oct 2024: Bloomberg reveals that Arm has told Qualcomm that it is canceling its Architecture License Agreement.

Oct 2024: Qualcomm announces the Oryon 2 core in the next Snapdragon 8 series of smartphone SoCs.

So to summarize:

Nuvia was designing Arm-compatible CPU cores destined for data centers. Nuvia was purchased by Qualcomm. Nuvia’s work was then repurposed to form the basis for Qualcomm’s Oryon cores designed for use first in laptops and now on smartphones.

Arm claims that in doing so Nuvia and Qualcomm have both breached the terms of their license agreements allowing them to use Arm’s technology. As a result, Arm has sued Qualcomm and canceled these licenses. Qualcomm disputes these claims.

Qualcomm’s Ambitions: Oryon Cores and Their Uses

To understand the importance of this case, we need to examine Qualcomm’s Nuvia-derived Oryon cores. The First Generation of Oryon was announced in 2023 and the Second Generation at this year’s Snapdragon summit in October.

Readers who have time to spare can watch the whole of the Snapdragon Summit Keynote 2024 (2.5 hours) - with the Oryon section linked directly - below:

Although there was a lot of talk - of course - about AI in the keynote the real center of the presentation was the performance of the new Oryon cores. AI was the ‘sizzle’ but Oryon was the real ‘steak’ in the keynote. Arm, of course, wasn’t mentioned at all.

Why are Oryon cores so important? Put simply the promise of these Oryon cores is that they provide a step change in performance for processor cores used in power-constrained devices like laptops and mobile phones.

Crucially they have promised to provide better performance and power consumption than alternatives from Intel, AMD and from Arm itself.

The First Generation Oryon cores have promised to give Qualcomm the ability to create an Arm SoC for Windows laptops that are, for the first time, competitive with x86 cores from Intel and AMD.

I’ve highlighted “promise” above as we won’t go into detail on whether the Oryon cores deliver on their performance objectives, particularly against the latest laptop designs from Intel and AMD. What is certainly true is that Oryon v1 delivered Arm cores that were, for the first time outside of Apple, competitive with x86 designs.

Now, Qualcomm is using Nuvia-derived Oryon v2 technology in its Snapdragon smartphone SoCs. The Second Generation Oryon cores provide Qualcomm with a claimed step change in the performance of its smartphone SoC cores.

If there was any doubt about how important the Nuvia team and their work are to Qualcomm, Nuvia founder Gerard Williams was welcomed to the stage at the Snapdragon summit by Qualcomm CEO Cristiano Amon with a friendly slap on the back.

Summing up, Oryon cores have provided Qualcomm with a step change in performance compared to the Arm-designed CPUs they previously used.

They are central to Qualcomm’s strategy to enter new markets including Windows laptops and grow market share in others like smartphones.

Arm’s Ambitions

We’ve covered Qualcomm’s ambitions for Oryon, but what about Arm? There are three key points to make.

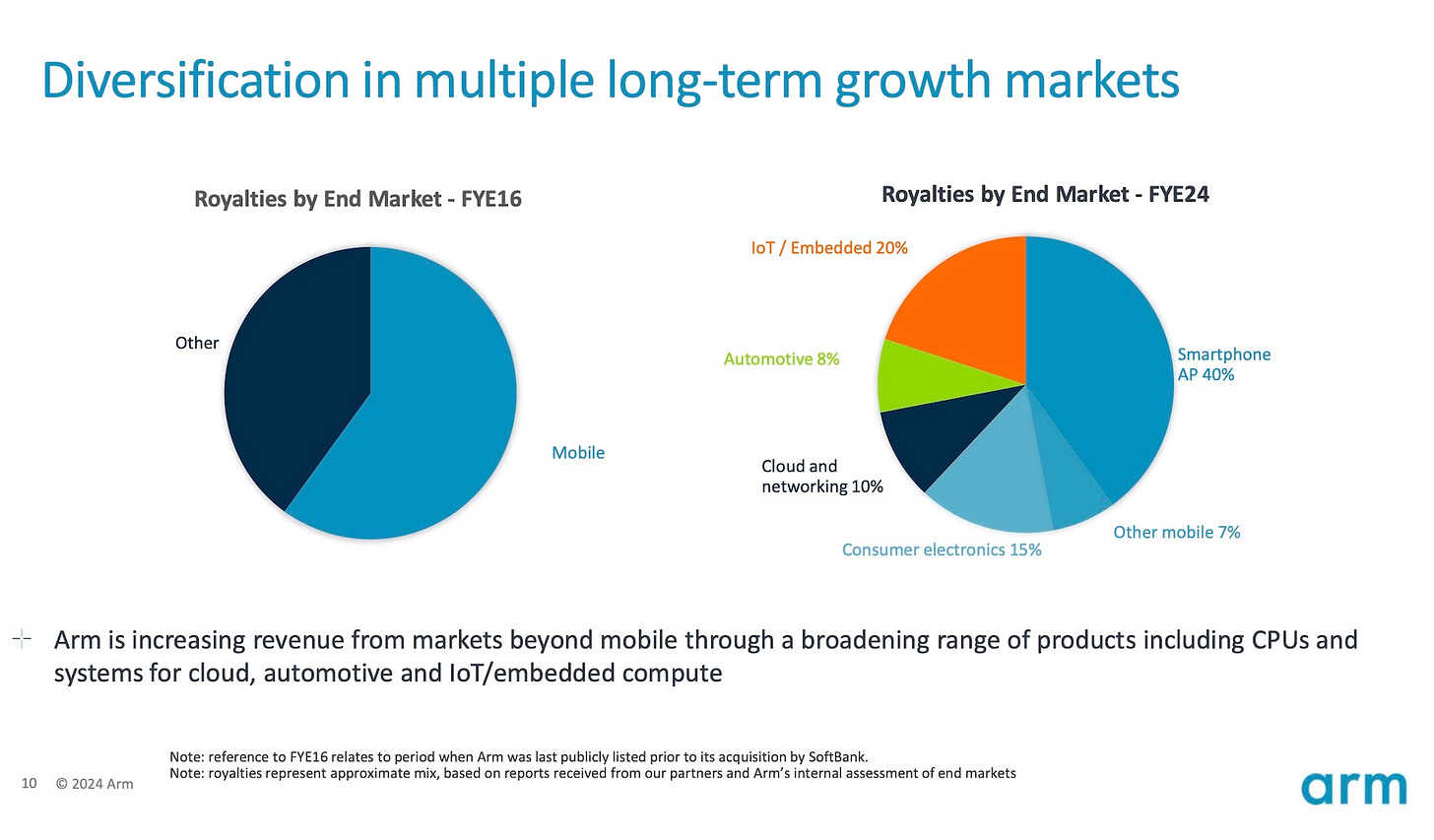

First, it’s easy to think of Arm as a smartphone and microcontroller CPU company. However, Arm’s business now has a material presence in several other markets including automotive and the cloud.

Desktops and laptops are notably absent here but Arm has ambitions here too. In June Reuters reported that:

Taiwanese chip design giant MediaTek is developing an Arm-based personal computer chip that will run Microsoft's Windows operating system, according to three people familiar with the matter.

The chip is based on Arm's ready-made designs, which can significantly speed development because less design work is needed using ready-made, tested chip components.

Second, Arm currently generates a relatively low royalty from each design that ships with Arm cores. Quoting SemiAnalysis last year:

Arm powers a whole multitude of chips for various end applications, and the nature of the Arm ISA means it is well-suited to certain applications. Arm has a total monopoly for instruction sets for smartphone application processors. There is simply no alternative as they have almost 100% market share. Our analysis suggests that Arm only makes about 50 cents per application processor on the >1B smartphones shipped per year. This seems awfully low for a foundational part of every smartphone with no viable alternative for chip designers to turn to.

Arm knows this and is now making these changes.

The whole post is worth reading:

One of these changes is the move from v8 to v9 of the Arm architecture. From Arm’s most recent quarterly presentation to investors:

Why is this significant? As the slide above highlights Arm v9 ‘commands a higher royalty per chip than prior architectures’ including v8.

Notably all Qualcomm’s Oryon cores remain on v8 with its lower royalties.

Also important is that Qualcomm’s Snapdragon doesn’t use other Arm designs, such as Mali GPUs, limiting the revenue that Qualcomm generates for Arm.

In short, Arm wants to increase the revenues it generates from its designs. Qualcomm and its approach with Oryon and Snapdragon put significant obstacles in the way of those ambitions.

Finally, although Arm floated on the NASDAQ in 2022, it remains roughly 90% owned by Masayoshi Son’s Softbank. It’s usual to talk about ‘Arm suing Qualcomm’ but Son, as CEO of Softbank and Chairman of Arm, has certainly approved the key decisions in this case.

Son is sometimes called the ‘Warren Buffett of Japan’. It’s an inaccurate nickname in many ways but it does, I believe, ring true in one respect. Both can take a long-term perspective and, indeed, Son has often discussed his willingness to invest in Arm to deliver long-term returns. Son is more likely to be focused on the long-term future of Arm and the Arm architecture than most.

Architecture License Agreements: What and Why

So Qualcomm and Arm both have ambitious long-term plans. But why would those ambitions clash, given that Qualcomm Oryon designs utilize the Arm instruction set architecture and Qualcomm pays Arm royalties on those designs?

To understand why, we need to explain the licensing agreements at the center of this dispute.

Most Arm customers license the use of processor cores designed by Arm itself. These licenses are known as ‘Technology License Agreements’ or TLAs.

In a limited number of cases, Arm has issued licenses that instead allow firms to create and use their own processor core designs that are compatible with the Arm instruction set. These licenses are known as ‘Architecture License Agreements’ or ALAs.

In How Intel Missed the iPhone: The XScale Era, we saw Arm grant the first ALA to Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in the mid-1990s that allowed DEC to create the StrongARM series of processors. Arm’s rationale for giving DEC the ability to design and sell Arm processors was that, at that time, Arm didn’t have the resources to create a design as powerful as StrongARM in-house.

However, doing so created risks. In a pre-echo of the current dispute with Qualcomm, the sale of the StrongARM business to Intel led Steve Jobs to suggest to Arm’s CEO, Robin Saxby, that they cancel the license. Quoting that earlier post:

“Intel acquired Digital and Intel got the rights to the Arm license through that contract … I had to get board approval on every deal. I discussed it with Apple and basically Steve Jobs … sorry he's not around anymore … was not in favor of licensing Intel and tried to stop me doing it. I spoke to him on the phone and he said you're the Chief Executive of ARM Robin, who am I to argue with you and he approved the deal.”

And here, although Saxby’s view prevailed, there was a credible argument to be made against transferring the architecture license to Intel. ARM was a minnow (turnover £27m - around $45m - in 1997) compared to Intel (1997 turnover $25bn).

Intel couldn't compete directly with ARM by licensing its designs to third parties, but they might represent formidable competition for other firms considering adopting ARM’s own, less powerful, processor designs.

Granting the first ALA was a risk for Arm. It might help spread the use of the Arm architecture but in the wrong hands, an ALA might allow a firm to take business away from Arm’s designs. In the worst case, a firm might use these designs to create a dominant position within the Arm ecosystem, weakening the position of other firms.

As we’ve seen, Intel fumbled its ownership of StrongARM and sold the business to Marvell in 2006.

Arm has since granted many more ALAs since the StrongARM license. ALA holders include firms like Google, Microsoft, AMD, Broadcom, and perhaps most famously Apple, which makes the CPUs in its A-series and M-series chips in iPhones and Macs under an ALA.

Returning to this legal case, both Nuvia and Qualcomm held ALAs:

Nuvia acquired an ALA in 2019 to allow it to create its Arm-compatible data center CPUs

Qualcomm has had its own ALA from before 2012. It once used that ALA to develop and sell its own Krait Arm ISA-compatible cores used in Snapdragon mobile SoCs. It later abandoned these efforts and switched to Arm processor designs licensed under separate TLAs.

However, it’s crucial to note that these two ALAs are not the same.

There are several crucial differences to highlight:

The legal submissions for this court case make it clear that the Nuvia ALA is more restrictive in some ways (and more permissive in others) than the Qualcomm ALA.

The Nuvia ALA carries higher fees than the Qualcomm ALA.

Arm also claims that it gave Nuvia substantial support in creating its new designs. Quoting Arm’s initial court submission:

”Arm also provided substantial, crucial, and individualized support from Arm employees to assist Nuvia in its development of Arm-based processors for data center servers.”

So, crucially, Arm claims it gave Nuvia help that would not have been available to Qualcomm under its ALA.

Granting the ALA to Nuvia made sense for Arm as it would generate additional revenues from expensive data center CPUs - a market Arm has previously struggled to break into - with (relatively) high license fees.

Qualcomm, however, after acquiring Nuvia had different ideas:

As we’ve seen, it wants to deploy derivatives of these designs more widely in laptops and now smartphones, and;

It wants to pay lower Qualcomm ALA royalties on these Nuvia-derived designs. Royalties that are also lower than the royalties it was previously paying (under TLAs) on the arm-designed cores it was previously using.

Let’s now try to understand the dispute, the arguments deployed by each side, the risks for each, and what might happen next.