Source Control

What to make of 'Source Code', the first volume of Bill Gates's memoirs?

‘Source Code’ is the first volume of Bill Gates’s memoirs, covering his life up to 1978. That means his family, his childhood, his education, and the early years of Microsoft with a particular focus on the development, launch and success of Microsoft’s first product Microsoft BASIC.

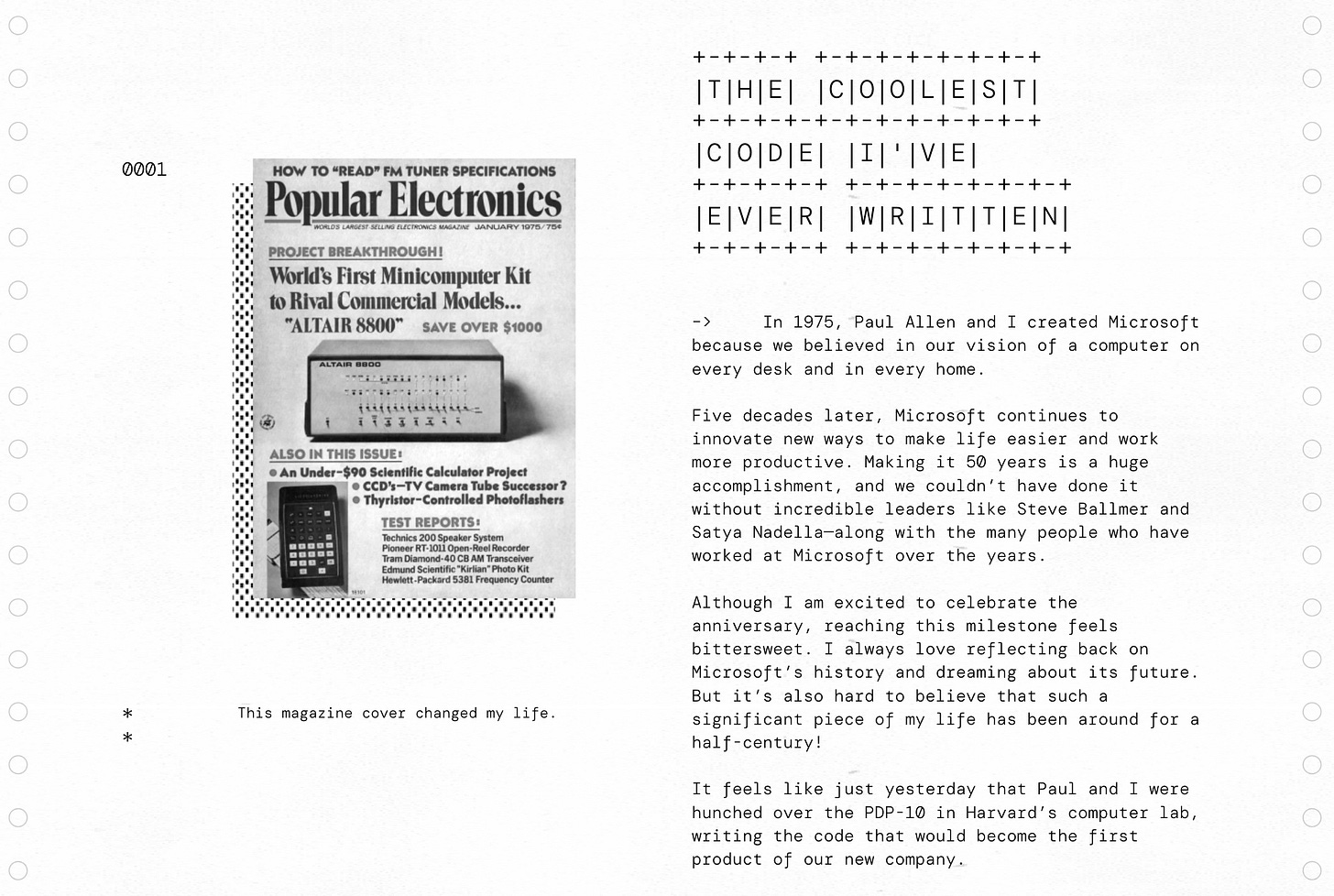

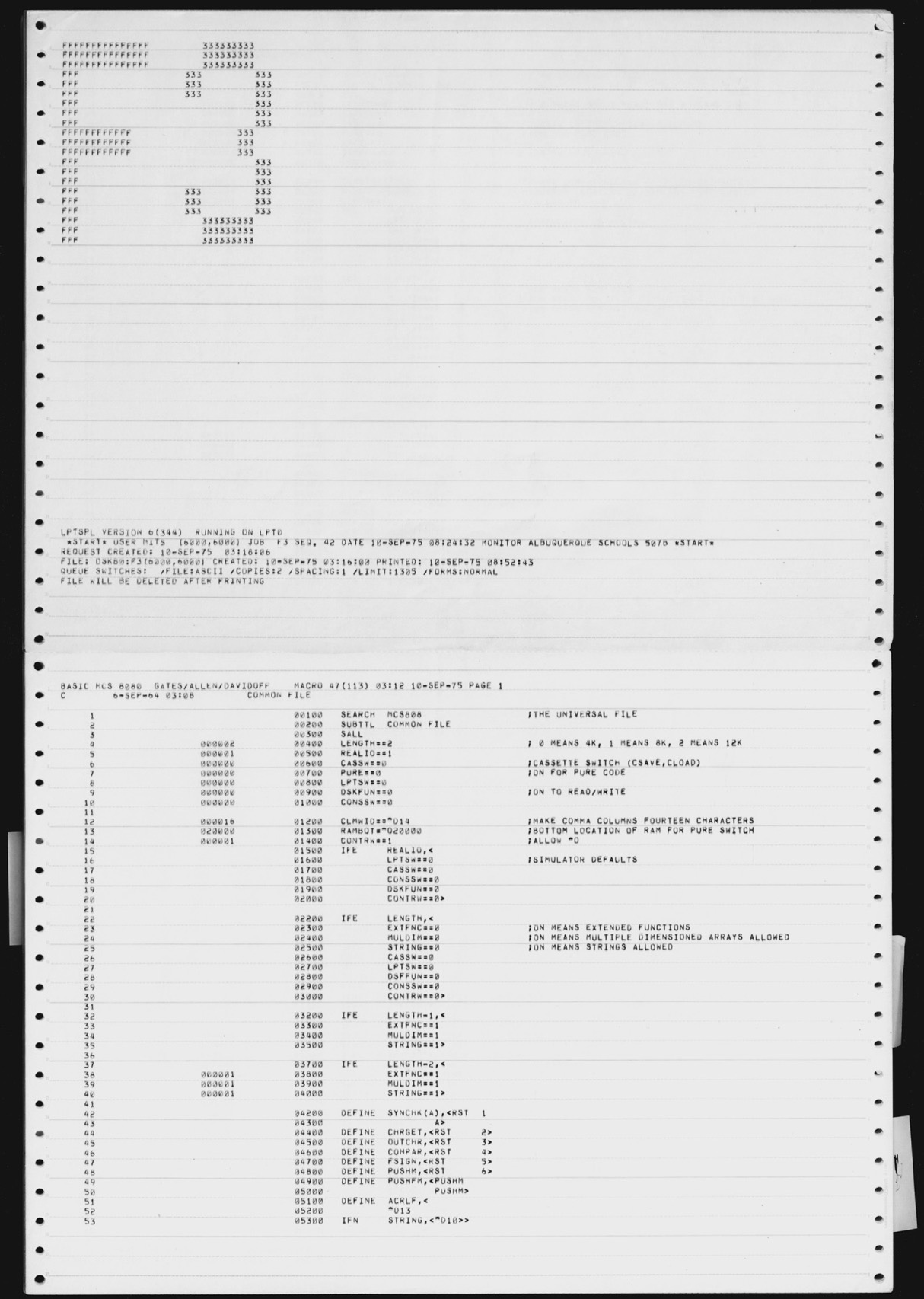

Accompanying the book has come the release of the source code for (a version of) the very first Microsoft BASIC running on the Intel 8080-based Altair 8800. I say ‘source code’ but it’s really a (100MB!!) PDF file and is linked to by a flashy landing page on Gates’s website (so flashy that it crashes some web browsers!).

Browsing through The Altair BASIC source code, though, is fascinating.

Gates has left it to others though to convert the PDF’s images into machine readable (and emulator friendly) code and there doesn’t seem to be a successful conversion so far (please let me know if you’ve found one).

As far as I can tell it’s still © Microsoft. Of course, Bill was never a fan of open source.

What to make of ‘Source Code’ the book though? It’s helpful to divide it into two halves. The first is largely about Gates’s family, upbringing, time at school and very earliest dabbling with computers. It ends with the death, in a mountaineering accident in May 1972, of Gates’s close friend Kent Evans.

The second half of the book is about the early years of Microsoft. It’s a story that is already well known, particularly from Paul Allen’s own book, the excellent ‘Idea Man’. As far as I can tell the Gates and Allen accounts are broadly consistent. ‘Source Code’ has more detail though, and of course it has Gates’s own personal perspective on these events, albeit from a distance of around five decades.

There is some technology in the book: discussion of programming on the DEC computers that Gates and Allen got started on, and of course of the Altair. There is greater focus though on the early days of Microsoft as a business and on Gates himself. The book is very much ‘Bill’s story’ with the ‘weight’ of the text focused on his rationale (or perhaps rather justifications) for the - personal and business - decisions he made over this period.

So what can we learn about Gates from the book? Four things stand out.

1. Bill cared … and still cares …

Why write this book? Gates clearly wants a wider audience to know about his story and, particularly, to understand his actions during the run-up to the founding and the early years of Microsoft. This is a project by someone who cares about what we think of him.

And - in a more intimate sense - it seems that Gates really did care about those around him in the 1960s and 1970s. The book - on the face of it, a fairly warts-and-all account of his relationships with his friends and colleagues over this period - displays a vulnerability, for example, at Kent Evans’s funeral, probably not shared by some of his peers:

The clearest memory I have is of sitting on the steps of the school chapel and crying as hundreds of people filed inside for Kent's memorial service.

2. Bill had advantages …

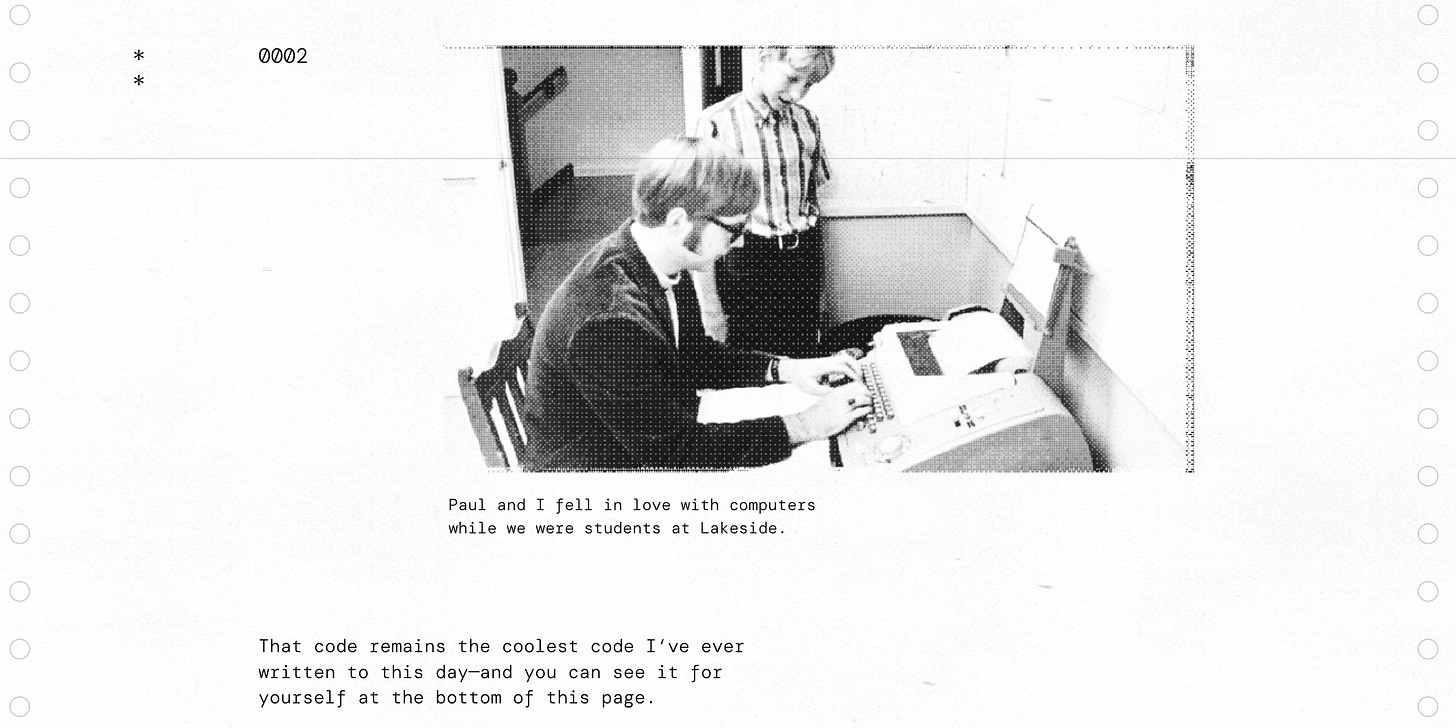

Gates attended the prestigious Lakeside private school in Seattle (ranked best private school in Washington State in 2024). His father, Bill Gates Sr., was the founder of his own law firm and, later, president of the Washington State bar association.

And Gates made full use of these advantages.

For example, Lakeside, crucially, had a DEC PDP-8 minicomputer on loan:

Around that time [1971], someone had loaned Lakeside a computer called a PDP-8, made by Digital Equipment Corp. This was 1971, and while I was deep into the nascent world of computers, I had never seen anything like it. Up until then, my friends and I had used only huge mainframe computers that were simultaneously shared with other people. We usually connected to them over a phone line or else they were locked in a separate room. But the PDP-8 was designed to be used directly by one person and was small enough to sit on the desk next to you. It was probably the closest thing in its day to the personal computers that would be common a decade or so later-though one that weighed eighty pounds and cost $8,500. For a challenge, I decided I would try to write a version of the BASIC programming language for the new computer.

Bill Gates Sr. would use his lawyerly skills to help his son’s early ventures, for example intervening in a dispute over computer time with time-sharing company ISI:

The ISI president spoke for a long time while my father just listened. When the man finished, my father simply said, "I hear you."

Those three words of my father's, and their tone, have stayed with me ever since. I hear you. To me, they captured the essence of my dad's quiet power. Unmoved by the man's arguments, my father simply acknowledged that he had noted them; in not saying anything else, he made clear that he did not accept them. The boys delivered, and now they were due what you had promised, was the implicit message I took away —and the ISI president seemed to get it too. With little more discussion, he agreed to give us the computer time.

And, as Microsoft’s business grew, Bill had ready access to a trusted, experienced (and free!) adviser, in the shape of his father. When preparing to sell Microsoft BASIC to Tandy, Gate’s recalls his Dad’s wise counsel:

My pitch, I told my dad, was that Microsoft could sell BASIC at a price far lower than Tandy could write a version on its own. I drafted two pages of talking points about how much better our product stacked up against anything else out there. My dad had advised me to simply be honest with Roach. If anything, he just gave me confidence. If I offered a great price and explained why it was a great price, Roach would probably listen.

Gates got the deal (if only after being shouted at by Tandy’s Roach in the meeting).

3. Bill stretched the rules …

And Bill’s father helped him to deal with one early problem arising from his repeated habit of stretching rules to breaking point. Gates and friends had racked up thousands of hours of unauthorised computer time at Harvard working on their own personal projects - the development of BASIC - time that would be paid for by the government research agency DARPA. Gates’s immediate reaction was - to day the least - unhelpful:

In notes I recently found in my Harvard records, he wrote, "He [me] did not understand the ramifications of his activities and seemed totally unimpressed when I explained them to him." Other notes in my record have him commenting that I was "a wise ass."

Once again, Dad’s advice helps save the day.

The Harvard incident is just one example of a pattern of Gates’s early attitude to rules that might have deterred someone else in his place. In fact part of a pattern of looking to push everything - his own work schedule, negotiations with partners, control of the market for BASIC - to its limits.

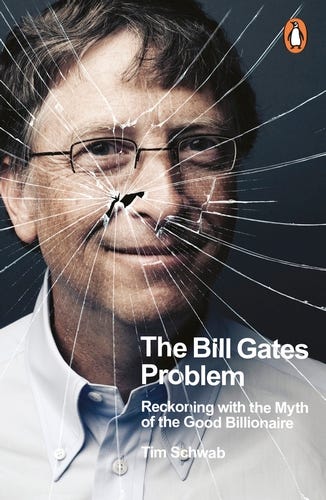

Which brings us to the final point, which became clear to me after reading another book, The Bill Gates Problem, by Tim Schwab.

In an era of ‘Gates conspiracy theories’ and the like, I had low expectations of this second book. Instead, I found a thoughtful and well documented exposition of a range of problems with the running of the Gates Foundation, the roots of which are neatly summarised in the book’s introduction …

If anything, his body of charitable work has been aimed at raising the volume of his voice. And he has very effectively used philanthropy to assert leadership over a wide array of topics, planting his flag and claiming dominion over the areas he pursued-from the so-called diseases of the poor to agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa to U.S. educational standards. Gates has ruled over these projects with a very clear ideology of how the world should work, devising solutions to social problems through innovation and technology …

In other words …

4. Bill wanted, and still wants, control

Perhaps the most telling episodes in the whole book are the brief accounts of how ownership of Microsoft was divided between Gates and Allen. First, Gates writes a note to his friend setting out why he should own 60% of (what was then called) ‘Micro-soft’:

"Micro-soft can do well because it is able to design and write good software and because it is able to take people, like Monte ... teach them, choose a project for them, provide resources and manage them. The monetary, legal, and management decisions involved are very difficult, as I'm sure you know. I feel my contribution towards these tasks entitles me to more than %50.percent of Microsoft."

We should split ownership of the company sixty-forty, I continued firmly. I thought that was only fair. "I have great optimism for our work together. If things go well I intend to take a full year off from school," I wrote in closing. Paul agreed to the split.

But even sixty-forty wasn’t enough for Gates, and he soon revisits the split.

Back in Albuquerque, I told Paul I wanted to make the split sixty-four-thirty-six. He pushed back. We argued, but eventually he gave in. I feel bad now that I pushed him, but at the time I felt that split accurately reflected the commitment Microsoft needed from each of us.

The justification for the first and then revised split on the grounds of commitment effectively make ‘fairness’ the underlying rationale. But it’s also clear that Gates wanted control of the business that he and Allen were building. The higher revised equity split would enable him to recruit Steve Ballmer - allocated a then modest, but now hugely valuable 4% - and still maintain his dominant shareholding.

It’s not hard to trace a line from this through Microsoft’s later actions to dominate the operating system, office applications and web browser markets, Gates’s difficult relationship with Steve Ballmer when Ballmer became Microsoft CEO, and all the way to how he now apparently runs the Gates Foundation.

And at the centre of this desire for control is Gates’s ego. This is, after all, the author of books called ‘How to Avoid a Climate disaster’ and ‘How to Avoid the Next Pandemic’.

‘Source Code’ is well written and highly readable. So should you rush out and buy it?

Yes, if you’re interested in Gates himself, in which case it’s an essential read to better understand the man.

If you want the early story of Microsoft then consider Paul Allen’s ‘Idea Man’ instead. If you do choose Source Code then prepare to flip quickly through the first few chapters.

If you’re solely interested in the technology of the early microcomputer era, then there are some interesting nuggets, but you might not enjoy much of the book.

I finished reading Source Code strangely unsatisfied. Perhaps I was just too aware that this book too - backed by Gates’s huge wealth and unrivalled media access - is part of Gates’s decades-long programme of control.

After writing this review I headed to Wikipedia to check on the ‘Reception’ section’s summary of critical reviews of ‘Source Code’.

Several reviewers noted Gates’s penchant for self-deprecation and his ability to humanize his success. Writing for The Guardian, Steven Poole remarked that Gates conveyed humility, in contrast to other tech titans. Poole wrote: "There is a sense of the writer, older and wiser, trying to redeem the past through understanding it better." David Shaywitz of The Wall Street Journal also praised Gates’s candidness, writing that the reader is "treated to an unexpectedly revealing account". In The New York Times, Jennifer Szalai liked the description of Gates’s youth but found that not much happened in many parts of the novel: "Source Code contains plenty of nicely rendered details, but as far as narrative tension goes, for the first 50 pages or so there is hardly any." She wrote that Gates might have to grapple with more difficult reflections on his later years in his two upcoming memoirs.

These are all fair comments. There is genuine self-deprecation and humanity in Source Code. But sometimes actions speak louder than words.

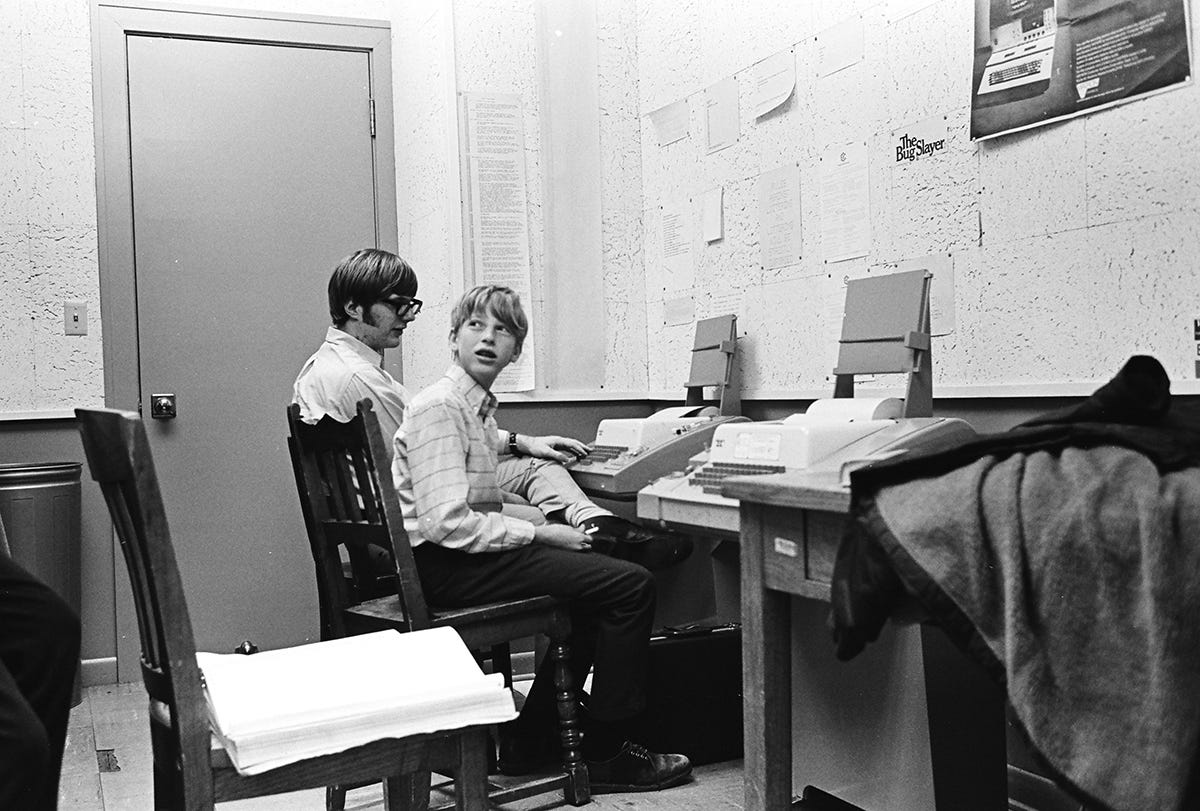

Image credit : Bill Gates in