The birth, rise and eclipse of the personal computer

A look back at the 'personal computer' at fifty.

The idea of the personal computer

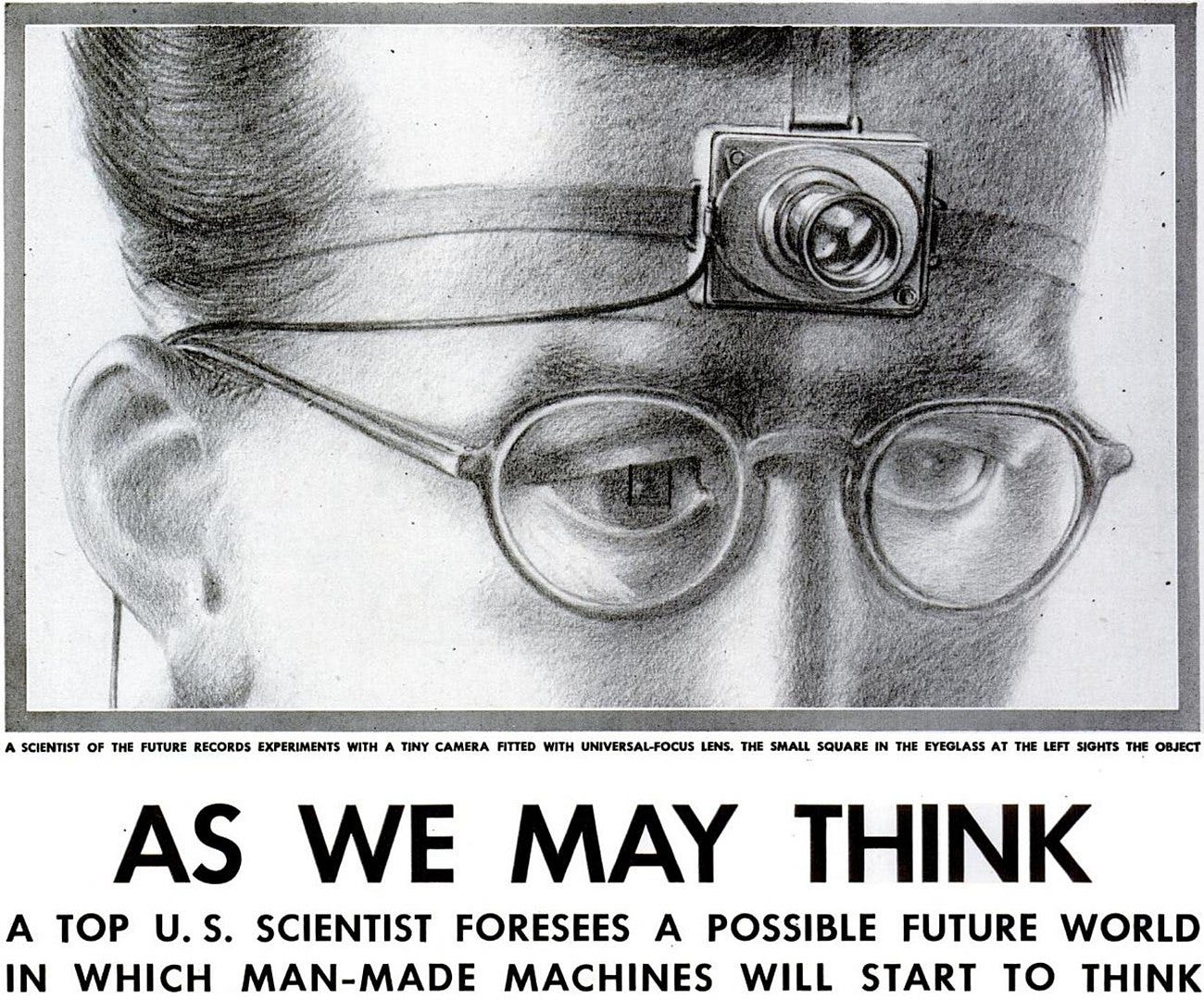

In The Innovators, his wide-ranging history of the development of computer technology, Walter Isaacson starts the chapter ‘The Personal Computer’ with a discussion of Vannevar Bush’s Memex:

The idea of a personal computer, one that ordinary individuals could get their hands on and take home, was envisioned in 1945 by Vannevar Bush. After building his big analog computer at MIT and helping to create the military-industrial-academic triangle, he wrote an essay for the July 1945 issue of the Atlantic titled "As We May Think.” In it he conjured up the possibility of a personal machine, which he dubbed a memex, that would store and retrieve a person's words, pictures, and other information: "Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library.... A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory." The word intimate was important. Bush and his followers focused on ways to make close, personal connections between man and machine.

The Atlantic article appeared a few months before ENIAC, the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer, ran it’s first practical program, one designed to help understand the feasibility of creating a hydrogen bomb. Bush led the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) which co-ordinated war related scientific research, including early work on atomic weapons. But with the war almost over, his thoughts were moving to his earlier interests in computers as tools for civilian research. In the 1920s and 1930s he had helped develop a mechanical analog computer - known as a ‘differential analyser’ - to solve differential equations. It’s perhaps not surprising then that he included a reference in his Atlantic article to Charles Babbage’s attempts to create a mechanical computer a century earlier:

Babbage, even with remarkably generous support for his time, could not produce his great arithmetical machine. His idea was sound enough, but construction and maintenance costs were then too heavy. Had a Pharaoh been given detailed and explicit designs of an automobile, and had he understood them completely, it would have taxed the resources of his kingdom to have fashioned the thousands of parts for a single car, and that car would have broken down on the first trip to Giza.

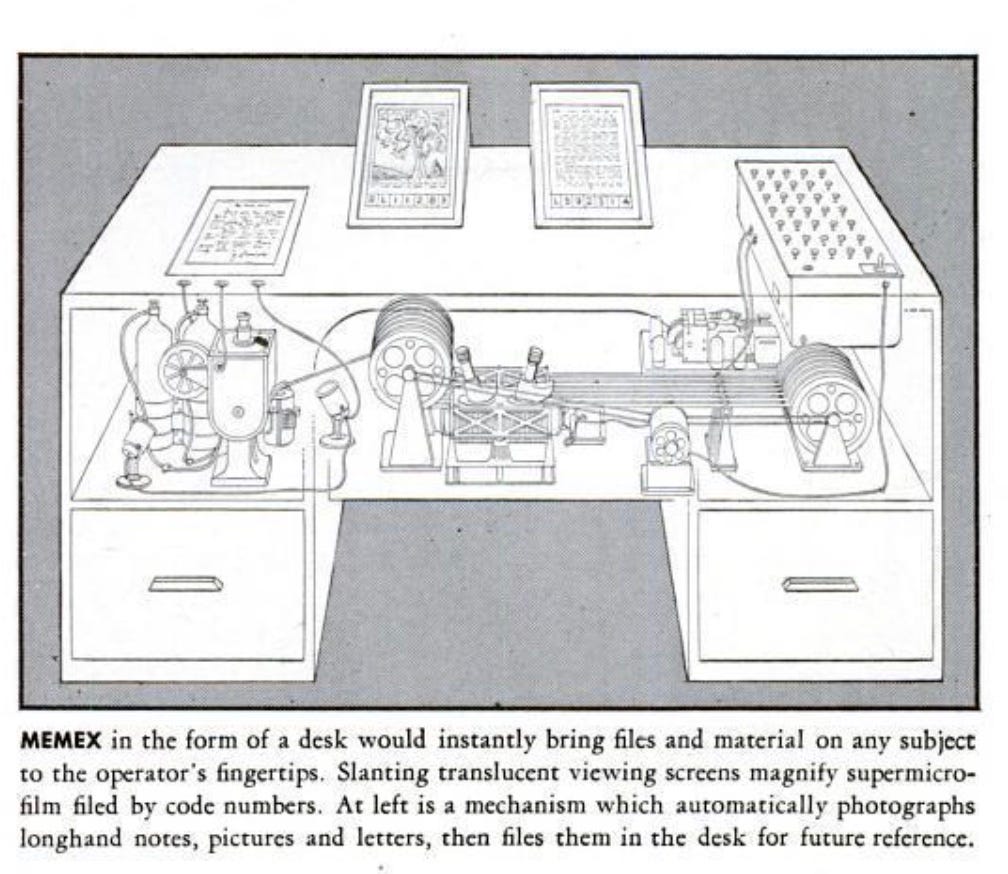

The ‘memex’ would be a modern tool for scientific research. In ‘As We May Think’ Bush describes both its form and the function:

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, “memex” will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory. It consists of a desk, and while it can presumably be operated from a distance, it is primarily the piece of furniture at which he works. On the top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. There is a keyboard, and sets of buttons and levers. Otherwise it looks like an ordinary desk.

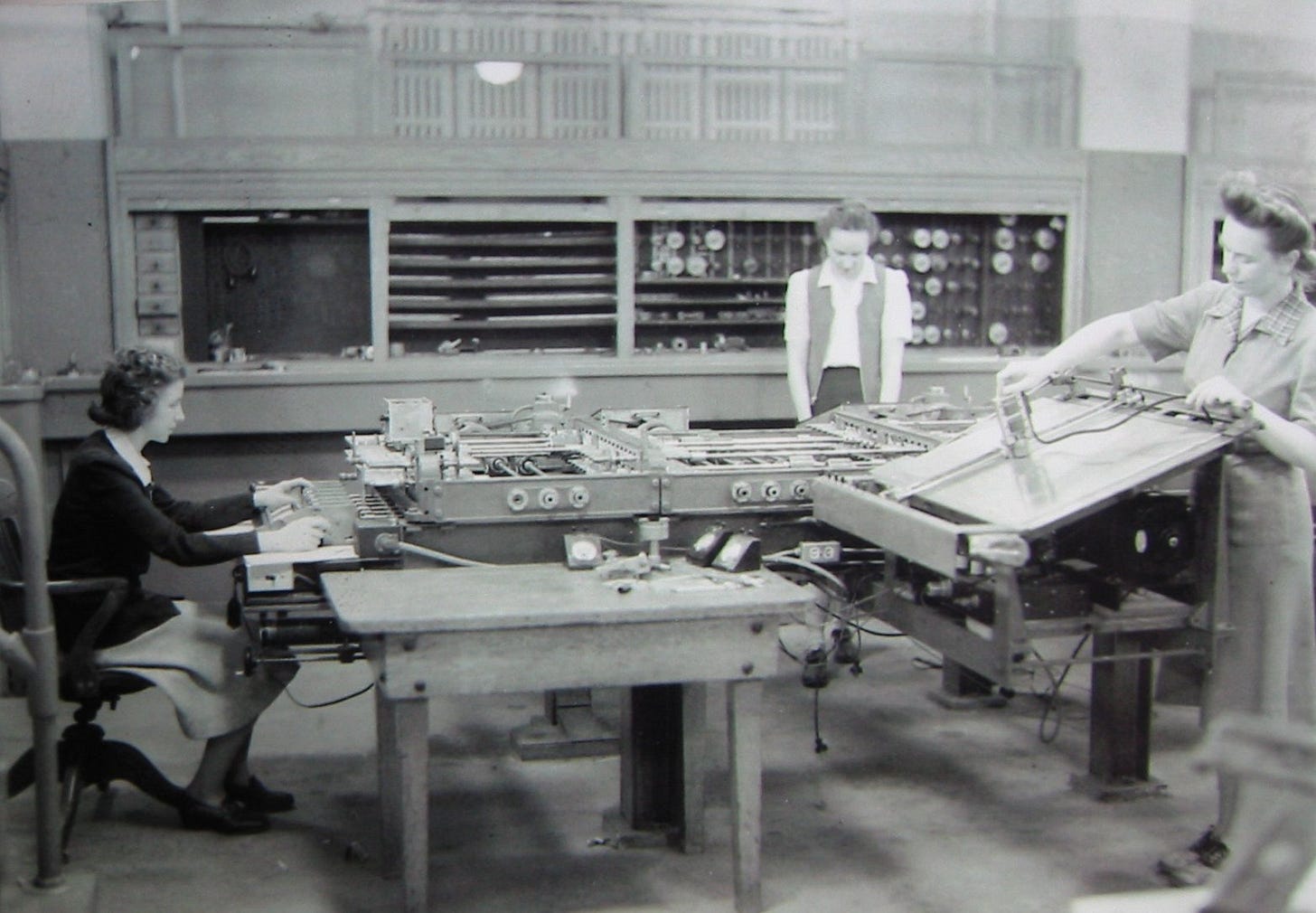

This might seem like quite a leap of imagination when compared to a room sized computer like the ENIAC. Yet it’s not that different in form to versions of the differential analyser that Bush would have been familiar with, for example, this machine in use at the Moore School of Engineering in the early 1940s.

The Atlantic essay was soon reprinted in abridged form in Life magazine, this time accompanied by illustrations of what some of the Bush’s devices, including the Memex, might look like.

Bush’s imagination wasn’t limited to the memex. Even more ‘personal’ was a slightly creepy looking ‘walnut-sized’ camera placed on an individual’s forehead, anticipating head-mounted image capture more than seven decades before devices from Snap, Meta and others.

Bush’s essay contains allusions to many other modern technologies including the internet, Wikipedia and more. It would inspire many who would go on to turn these ideas into reality.

Walter Isaacson devotes the majority of the rest of his chapter on ‘The Personal Computer’ to those who would build on some of Bush’s ideas, especially those in the West Coast of the US. In rapid succession we meet a diverse cast of characters and machines including Douglas Engelbart, with his ‘Mother of all demos’ including the first mouse, Alan Kay at Xerox PARC and his Dynabook, and the Xerox Alto.

The Alto, with it’s mouse and graphical user interface, really does look and feel like a modern desktop personal computer

The Altair 8800

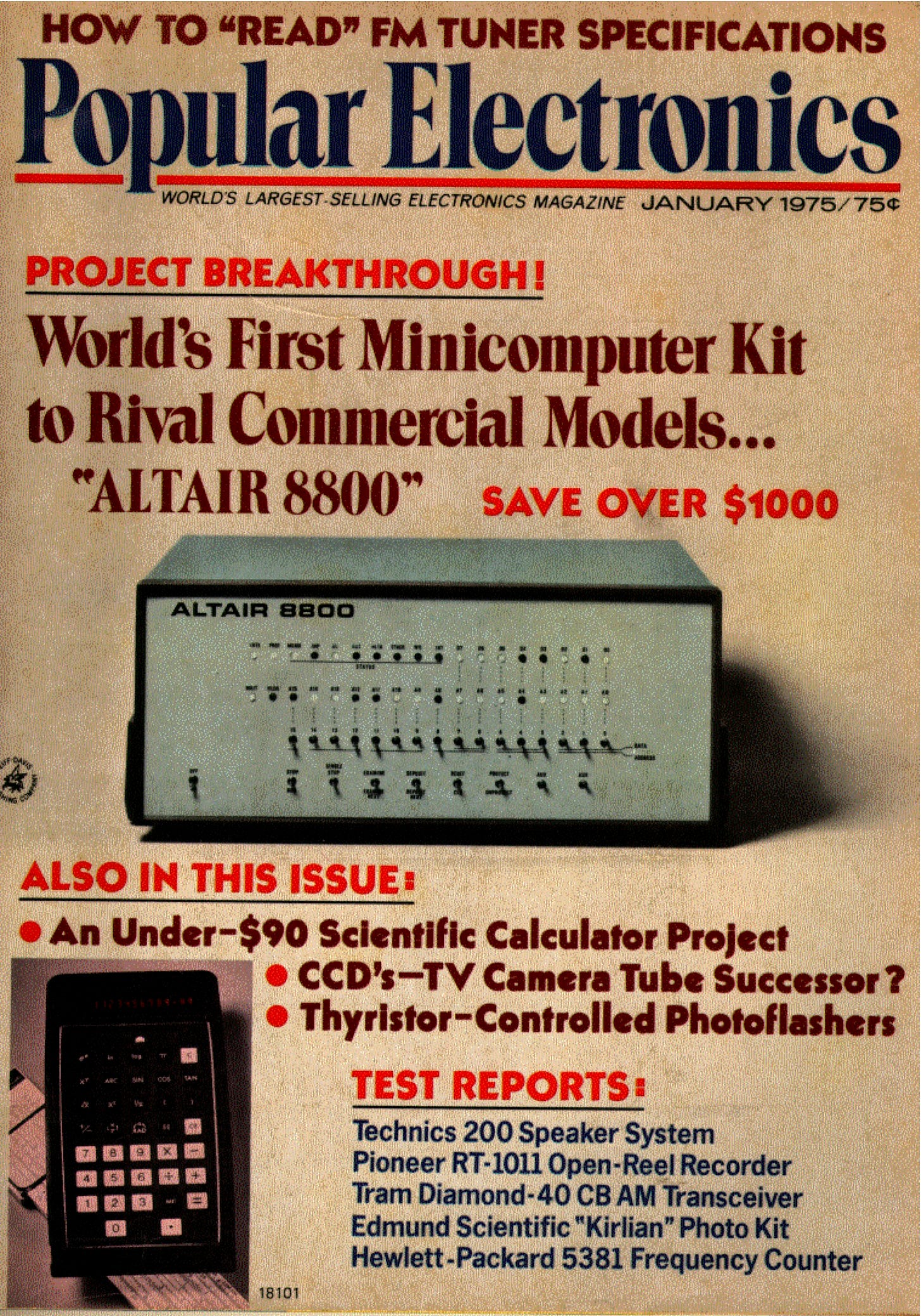

Yet at the end of his chapter on the ‘Personal Computer’, Isaacson makes an abrupt ‘u-turn’. He suddenly switches to a machine that has none of the distinctive features of the Alto. That machine is the Altair 8800, created by Ed Roberts and based around Intel’s 8080 microprocessor. It’s the Altair 8800 that many now call the first ‘personal computer’.

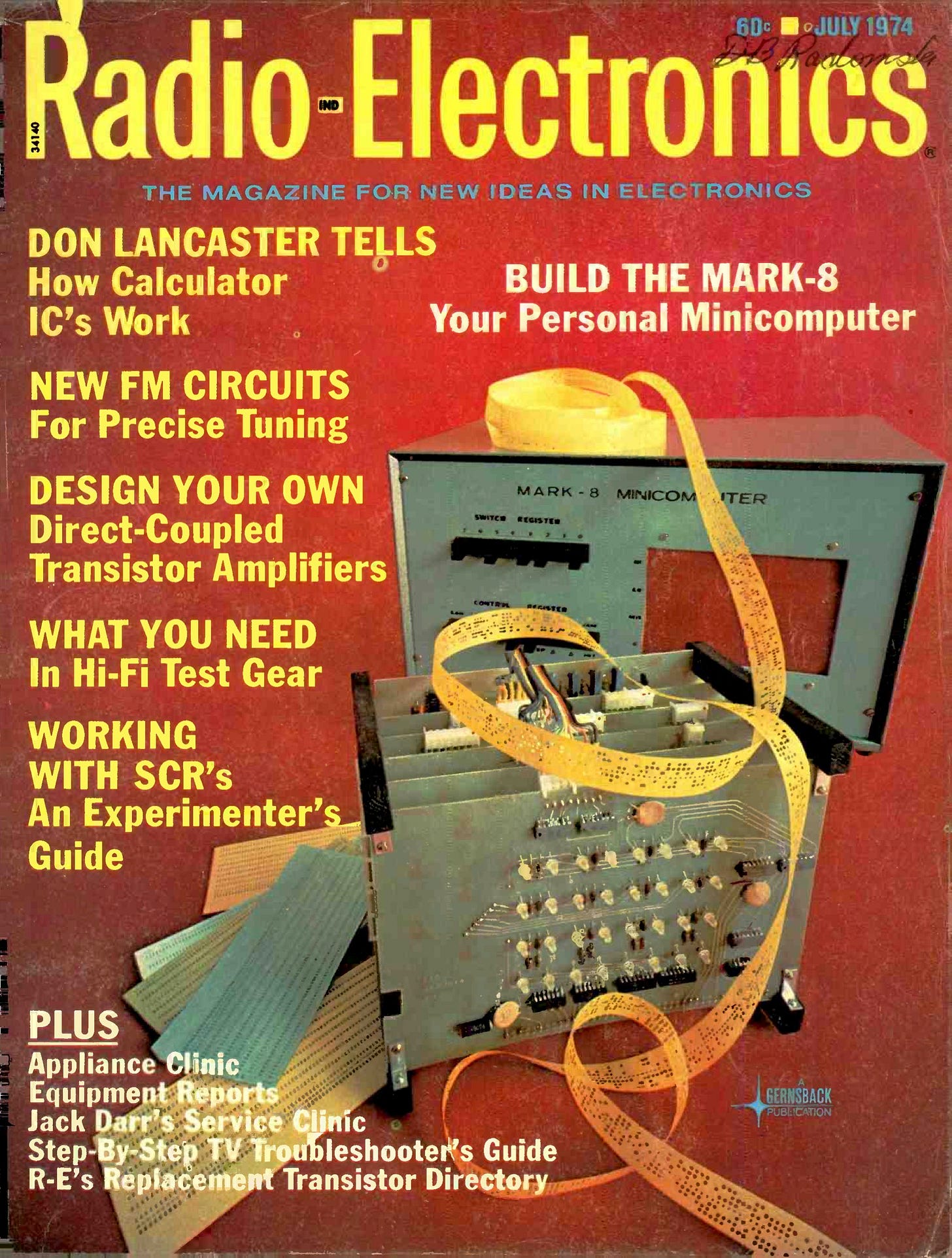

The Altair wasn’t the first machine of its type to appear. The Intel 8008 based Mark-8 computer appeared on the front cover of Radio Electronics a few months earlier. But, unlike the Altair, the Mark-8 was a set of designs rather than a product you could buy.

When the Altair was launched into the world, on the front cover of Popular Electronics in January 1975 there was no such thing as a ‘personal computer’. Instead it was described as the ‘World’s First Minicomputer Kit To Rival Commercial Models …’

The Altair resembled a minicomputer. It was big and heavy. It had a front panel with ‘blinking lights’. At first its ‘boot sequence’ had to be entered via the front panel and then users would interact with it via a teletype. This was definitely no Xerox Alto.

But it was affordable and it was expandable with expansion slots that owners could use to add RAM, floppy disk controllers and other third-party hardware.

Just eight months after the appearance of the Altair, the first edition of Byte magazine the terms ‘personal computer’ and ‘personal computing’ were gaining a firm foothold. Editor Carl T. Helmers Jr, in an article titled ‘The Impossible Dream’ wrote:

Along about 1972 when I started reading about the LSI computers being designed by Intel - the 8008 and 4004 - I began to revive that old dream of "having a personal computer."

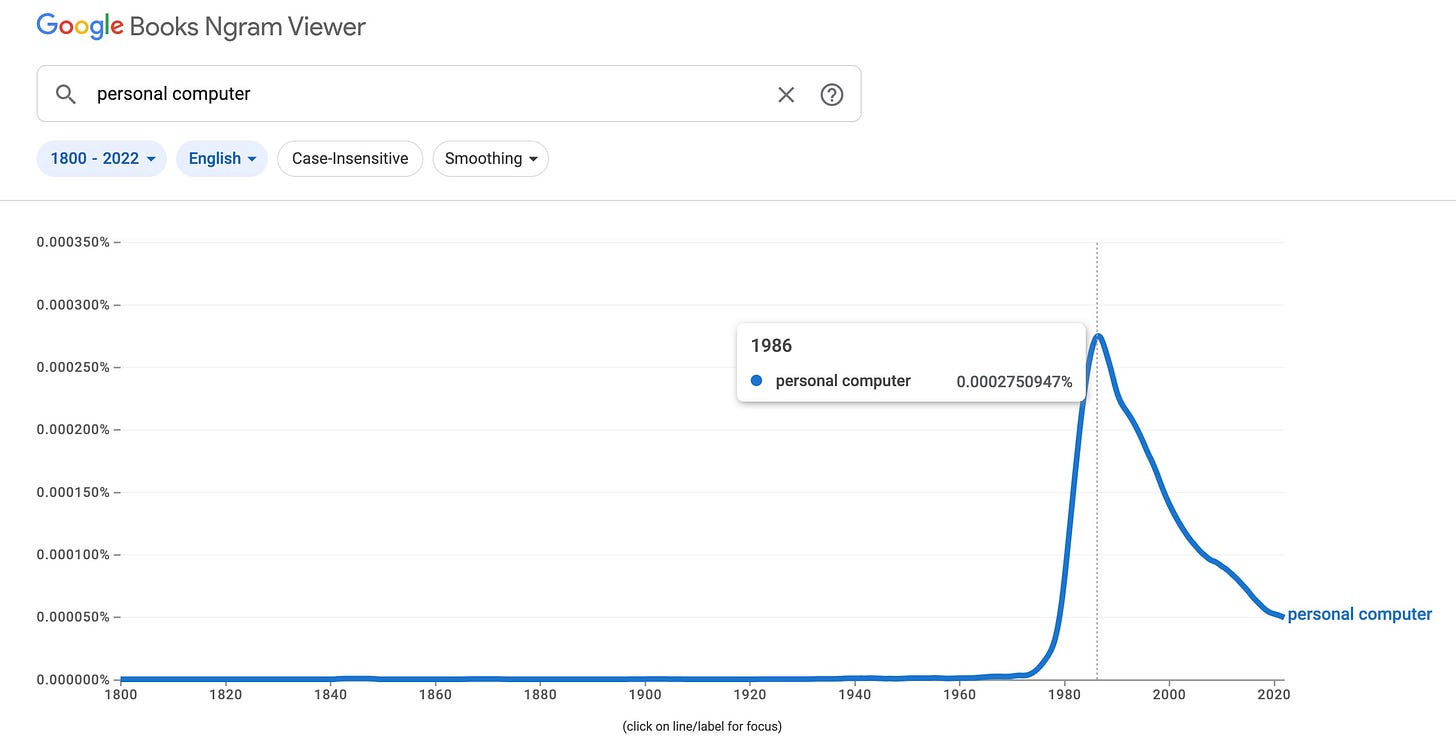

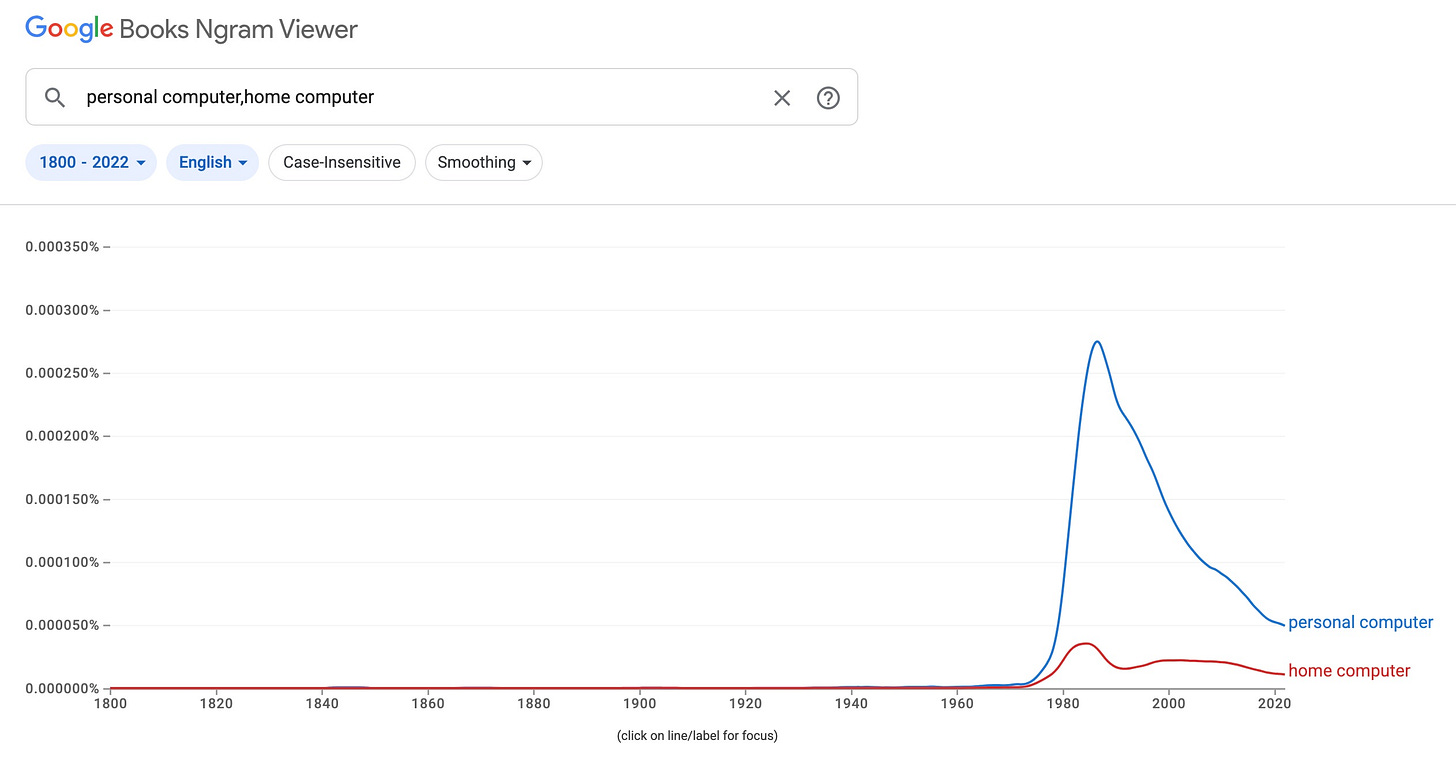

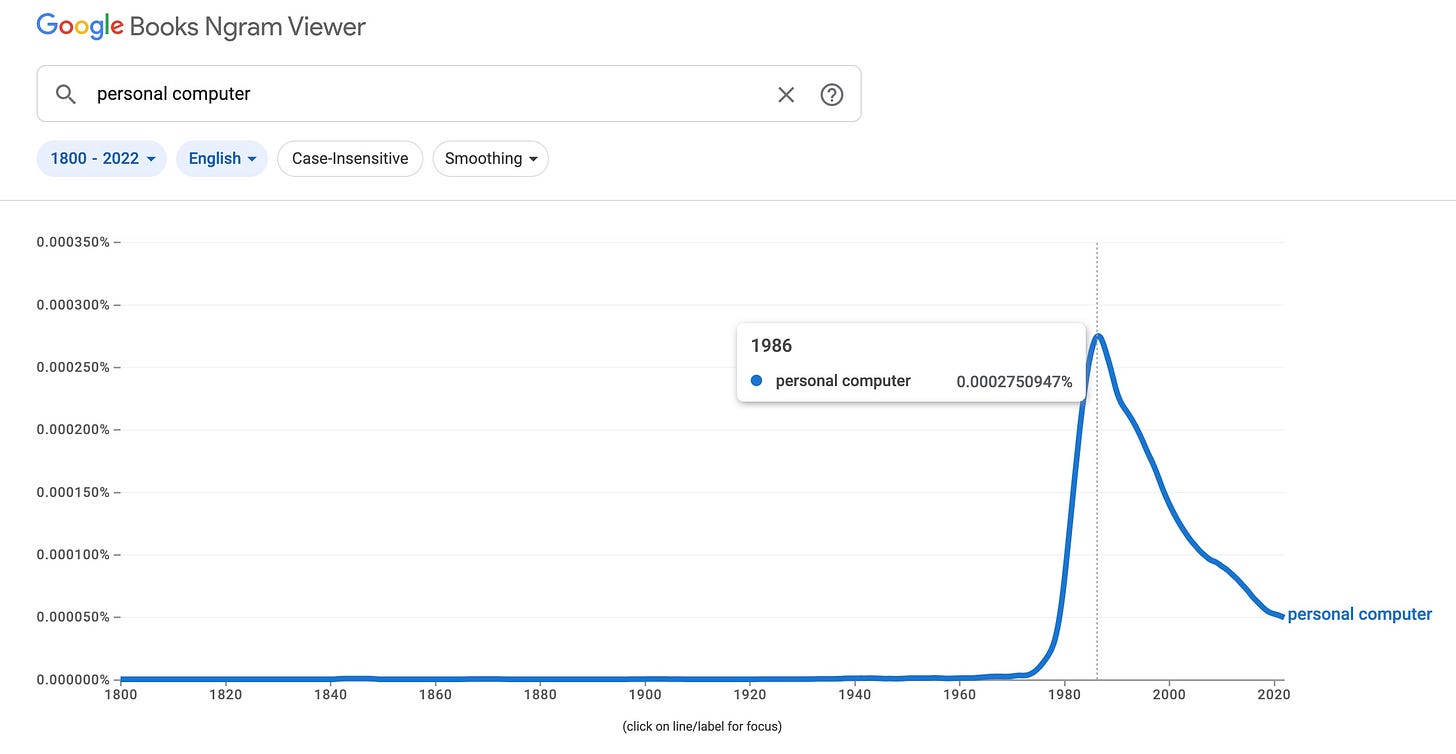

And the use of the term ‘personal computer’ soon took off, as the Google Ngram shows.

The mouse and graphical user interface were not pre-requisities for a machine being ‘personal’. Users would be just fine with a keyboard and text based interface.

That ‘impossible dream’ of having a personal computer would soon be realised by millions as sales of machines from companies like Apple, Atari, Commodore, Tandy and many others took off.

In fact many of these machines looked nothing like the Altair 8800 either. They had built-in keyboards, built in BASIC’s, built-in graphics and were often closed boxes. But like the Altair they were affordable and, in many key respects, they were open. Owners soon got to work ‘peeking and pokeing’ around in their machines, understanding them, hacking them.

And although these machines were sometimes referred to as ‘home computers’ the term was never as popular as ‘personal computer’. Firms tried to sell them as appliances for the home but they were really tools for the individual - often kids - rather than the family as a whole.

And many of these new machines were sold to businesses, both small and large. The IBM Personal Computer, when it was introduced in 1981, was not cheap:

Pricing started at $1,565 [$5,500 in 2025] for a configuration with 16 KB RAM, Color Graphics Adapter, keyboard, and no disk drives. The price was designed to compete with comparable machines in the market.

Add in more RAM and some disk drives and you’re close to $10,000 in 2025 money.

Discussing the IBM PC leads to the need for some disambiguation: personal computer in lower case distinguishes it from the IBM Personal Computer, which soon, as IBM lost control of it’s design, became just the PC or Personal Computer.

An anecdote from the early days of the IBM PC. Even if the first IBM PCs were mostly bought by businesses rather than for use at home, their price and accessibility meant that individuals could often buy, install and use them without going through complex corporate approval processes. I remember once when a finance manager got his corporate cheque book out (it was 1984!) to buy two IBM PCs on the spot when he first saw Lotus 1-2-3 (the most popular spreadsheet for the original IBM PC) in action. Those machines may not have been going home with him, but I expect that he saw them as his ‘personal computers’.

The microprocessor computer?

The take off in ‘personal computing’ was enabled by microprocessors from Intel, Motorola, MOS Technology, Zilog and others in the mid 1970s. Cost was a key part of this. Intel selling the 8080 to Ed Roberts for $75 enabled him to sell the Altair for around $400, an order of magnitude less than it would have cost to build a processor out of discrete components. Even the more costly IBM PC was much cheaper than IBM’s other computers.

But it wasn’t just about price. Microprocessors could be manufactured in the millions, turning the computer into a ‘mass-market’ device for the first time. It allowed firms with a talent for industrial design and marketing to create computers that were attractive for millions of consumers. The use of a common ‘part’ for the processor allowed computer makers to focus on other aspects of their designs and on their businesses and to utilise software developed for other machines.

That doesn’t mean though that every microprocessor based computer was (or is) a personal computer. Neither a DEC VT100 Terminal with an Intel 8080 microprocessor, nor a SPARC-based workstation from Sun Microsystems qualify as ‘personal computers’.

But IBM understood what was needed to make the IBM Personal Computer truly a ‘personal computer’, both in the design of the machine and in the way it marketed it.

Take the launch ad, with it’s choice of Charlie Chaplin’s ‘The Tramp’ character. The most famous and admired film featuring ’The Tramp’ is Modern Times, about which Chaplin’s biographer Jeffery Vance has written:

The twentieth-century theme of the film, farsighted for its time—the struggle to eschew alienation and preserve humanity in a modern, mechanized world—profoundly reflects issues facing the twenty-first century. The Tramp's travails in Modern Times and the comedic mayhem that ensues should provide strength and comfort to all who feel like helpless cogs in a world beyond control.

‘The Tramp’ strives for control in a world where many feel that they are helpless cogs.

What ‘The Tramp’ character did in that first ad is telling too. Steve Jobs said ‘never trust a computer you can’t lift’ when introducing the Macintosh in 1984. And yes ‘The Tramp’ is seen lifting the IBM PC out of its box, dancing as he goes.

And the design of the IBM PC resembled its ‘personal computer’ forebears. Users could hack both the hardware - via expansion slots - and the software.

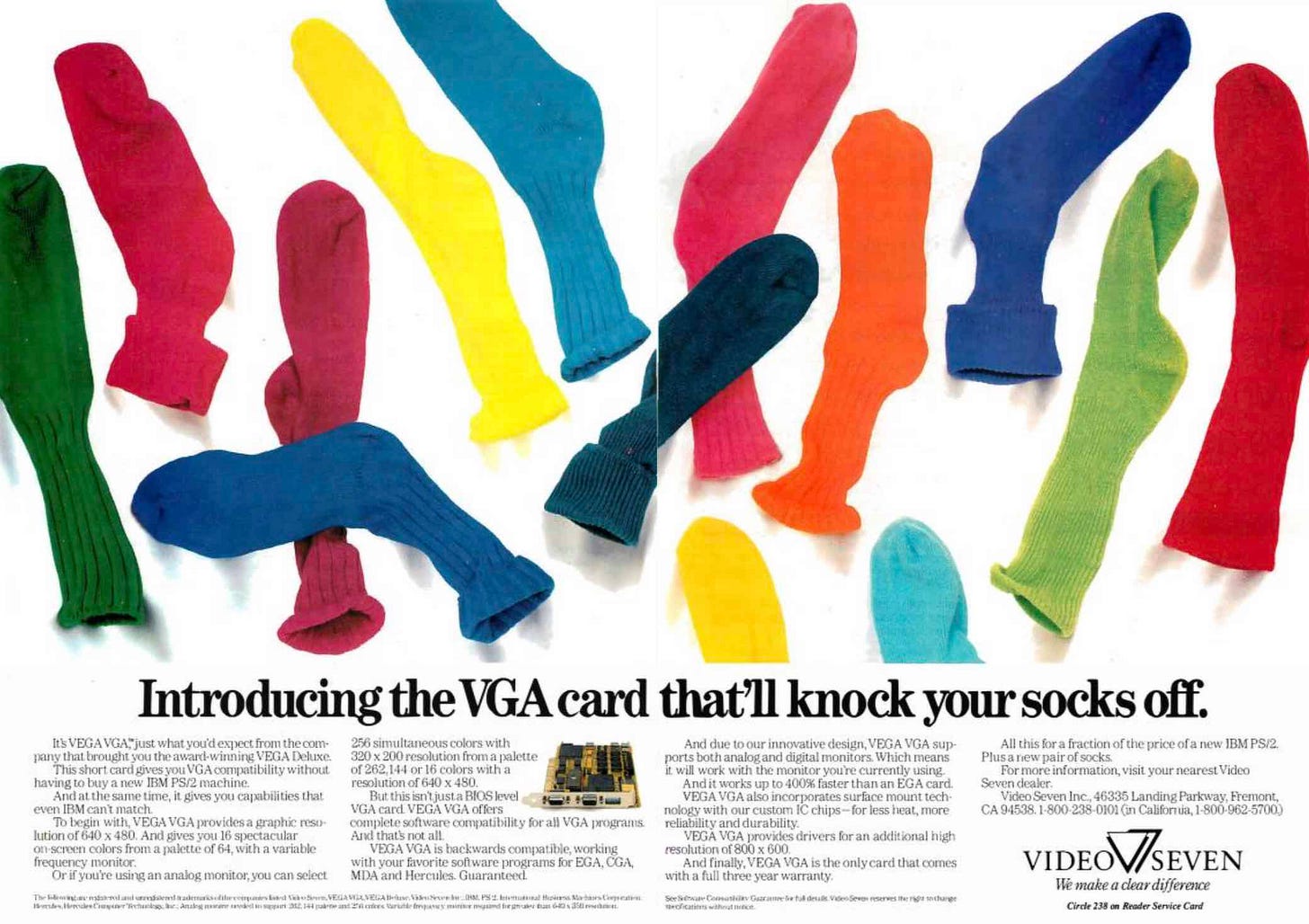

With its flexibility, openness and the heft of IBM behind it there was soon an explosion of creativity building on the IBM PC ‘platform’. There were video cards, audio cards, co-processors and much more. Leaf through any computer magazine from the mid 1980s and there are hundreds of PC products being discussed or advertised. You can sense the creativity from the marketing for products and companies that have been long forgotten.

IBM itself even got into the spirit and made a mainframe compatible machine on top of the PC with the PC XT/370.

The response from Apple? Famously, the firm tried to invoke George Orwell’s 1984 during the launch of the Macintosh in - of course - 1984.

Yet something didn’t quite ring true about this attempt to portray IBM as ‘Big Brother’, at least when it came to the IBM PC.

Because, even though the Macintosh - building on the ideas of the Xerox Alto - was more ‘user friendly’ in many respects, the IBM PC was more ‘personal’. It was more affordable. It was more expandable. It was more flexible. It was more open. Users had more control over their PCs than over their Macintosh’s.

As we know the PC - with its astonishing open ecosystem - won.

The eclipse of the personal computer

Let’s return to that Ngram for ‘personal computer’. Use of the term peaked in 1986, fell rapidly in the years that followed, and has been in steady decline ever since.

We can guess many reasons for this. Perhaps use of the ‘PC’ abbreviation took over. Or as most computers were ‘personal’ the use of just ‘computer’ was sufficient in many cases.

But the ‘personal computer’ has also been eclipsed. The smartphone is now the primary computing device for most people, yet we don’t call our smartphones personal computers. When Steve Jobs announced the iPhone in 2007, he described it as the combination of three devices: an iPod, a mobile phone and a ‘breakthrough internet communications device’. Apple soon lost ‘Computer’ from its name.

So the decline in the use of ‘personal computer’ is consistent with another change: ‘personal computers’ have become more intimate but less personal. We have much less control over our smartphones and tablets than we have over our computers.

And users have also lost control over many aspects of their work on their personal computers. In some cases these machines are devices that are largely used to run a web browser with users ceding much control over how their machines are organised and managed.

It’s not windows, icons, mice, touchscreens or ‘intimacy’ that made ‘personal computers’ personal. Vannevar Bush’s vision and beyond has been reached but much of the original spirit of the real original ‘personal computer’ has been lost.

Really enjoyed this. Very nice work. Thinking about where you ended this. Compute - and computers - have been greatly democratized - but, as you say, with less ability to mod, to paraphrase you a bit. You could probably pair this with data on how the incremental cost of storage has declined.

Most people don't seem to realise just how open the original Macintosh really was. Sure, it didn't have internal card slots like the Apple ][ and IBM PC, but that's really the only difference.

Just like on MSDOS, once an application was launched it had total control over the machine. Sure, there was a large ROM with a lot of useful routines for drawing graphics and UIs and other things, but nothing at all forced you to use it -- it was just super-convenient to do so. Like DOS but unlike Windows the main program loop was your code so with no address space protection you were in total control.

Not only could you use Mac library routines, you could also replace them with your own versions in several ways, lower level ones by patching the Axxx illegal instruction trap dispatch table entries that were used to call them, and for some higher level things such as menu and window drawing even just by adding code in a "resource" in either your application or in the desktop database file.

This was SO OPEN that it allowed the WDEF virus in late 1989 that replaced the window drawing code with code that called the standard one but also did some nefarious things (infecting disks). By the time this was discovered it had already spread all over the world, even in pre-internet times.

The IBM PC's "ISA" (named in retrospect) bus theoretically ran at up to 4.77 MB/s but in practice both 8088 load/store and DMA ran at 5 clock cycles per byte so maximum 1.13 MB/s or 9 Mbps.

The Mac's Zilog SCC serial ports (which cost about $5 more than the simple 8250 UART used in the PC, which supported maximum 115200 bps) ran at up to 230.4 kbps with the internal clock, or up to 1 Mbps with an external clock. The SCC also supported device addresses and ignoring data not meant for it, thus allowing multiple peripherals to be attached and indeed the LocalTalk network. With external clock the speed is not too far off modern USB LS's 1.5 Mbps which is used to this day for many keyboards, mice, joysticks, and communications to microcontrollers such as Arduino.

At the built in 230.4 kbps speed Localtalk used a simple cheap external transformer and allowed up to 32 computers to communicate over a network segment of up to 300m length. Farralon's "PhoneNet" connectors doubled this to 600m. Other companies produced networks operating at up to 1 Mbps from those serial ports.

That's on the original 128k and 512k Macs. Of course two years after the initial launch the Mac Plus in January 1986 added SCSI for higher speed peripherals at 0.25 MB/s. The next year's Mac II increased that to 1.35 MB/s.