What if you could read and watch extended interviews with almost 2,000 of the smartest people in computer science and engineering? People who have shaped the field, who have made many of the most important discoveries and who have founded multibillion dollar companies. In these interviews they tell their stories, talk about their influences, their education, about the obstacles they overcame and about their contributions to the field.

What’s more, you can read and watch these interviews for free.

Sounds like a wonderful resource?

I’m talking about the archive of Oral Histories at the Computer History Museum (CHM).

The CHM archive of Oral Histories has often been an essential part of the research that goes into Chip Letter posts. But even leaving aside their value as the starting point for research, these interviews are a tremendous resource.

Why do I love them so much?

True Giants In Their Field: We can hear from those who have made a huge contribution to computer science and engineering.

The Real Person: When we have the audio or video of the interview we can get a real ‘feel’ for the interviewee, their enthusiasm, their charm, (or grumpiness) and their skills in communicating their expertise. Even the (usually very lightly if at all) edited transcript can often convey this too.

No Axe to Grind (Usually): The obvious comparator is with ‘long form’ podcast interviews. But here the interviewee isn’t promoting their own book or podcast or product or doing PR on behalf of their company. They might have a score or two to settle though, which sometimes adds to the fun!

The Whole Picture: Usually taken at the end of a career we often get a complete ‘biography’ in a couple of hours, not just the story so far.

Expert Interviewers: Last but not least, the interviewers are usually highly knowledgable, often colleagues or experts in the field.

Of course, as unedited conversations they are less polished than books or articles, but that’s all part of the charm. And the interviews often go well beyond technical subjects. One of my favourite starts to an Oral History, is from Victor Poor who worked on the Datapoint 2200 Terminal:

Gardner Hendrie: Vic Poor has agreed to an oral history interview for the Computer History Museum and, right at the beginning, we thank you for being willing to do this. I think probably maybe the best place to start. Could you tell us a little bit about your family background, siblings, where you grew up, you know, when you were born, some of those things.

Victor Poor: Why? Does that have anything to do with computers?

Hendrie: Huh?

Poor: I said, does that have anything to do with computers?

Thankfully, the interview then proceeds more smoothly from this point onwards.

This is all great but there is just one problem. With almost 2,000 interviews, where do you start? This is one place where curation is most definitely useful!

Rather than fully imposing my personal preferences though, why not choose an independent judge as to the significance of the interviewees? Enter the Turing Award.

The ACM A. M. Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to computer science. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in the field of computer science and is often referred to as the "Nobel Prize of Computing". As of 2025, 79 people have been awarded the prize …

Even restricting to the Turing Award’s 79 recipients, a large number of whom have CHM Oral Histories, is probably too much though.

So here is my hand-picked selection of CHM Oral History interviews with seven Turing Award recipients. It covers computer hardware, software, algorithms, graphics, and the internet in more than 17 hours of video and nearly 500 pages of transcript. They have worked at IBM, Bell Labs, DARPA, DEC, Xerox PARC, Google, Sun and Microsoft. Most aren’t household names but they are all important and interesting figures.

If even that is too much then I’ve added AI (Google Gemini) generated summaries after the links to the video and transcripts. I’ll always disclose where and why AI has been used in posts. The rationale here is that it helps to remove my personal biases that would inevitably creep into my own hand-crafted summaries. Please use this as a starting point and listen to (some of) the actual interviews though; it’s really worth it!

We’ll start by breaking our curation rule though. Only 3 of the 79 recipients of the Turing Award have been women so we’ll start with a female computing pioneer who hasn’t received the award …

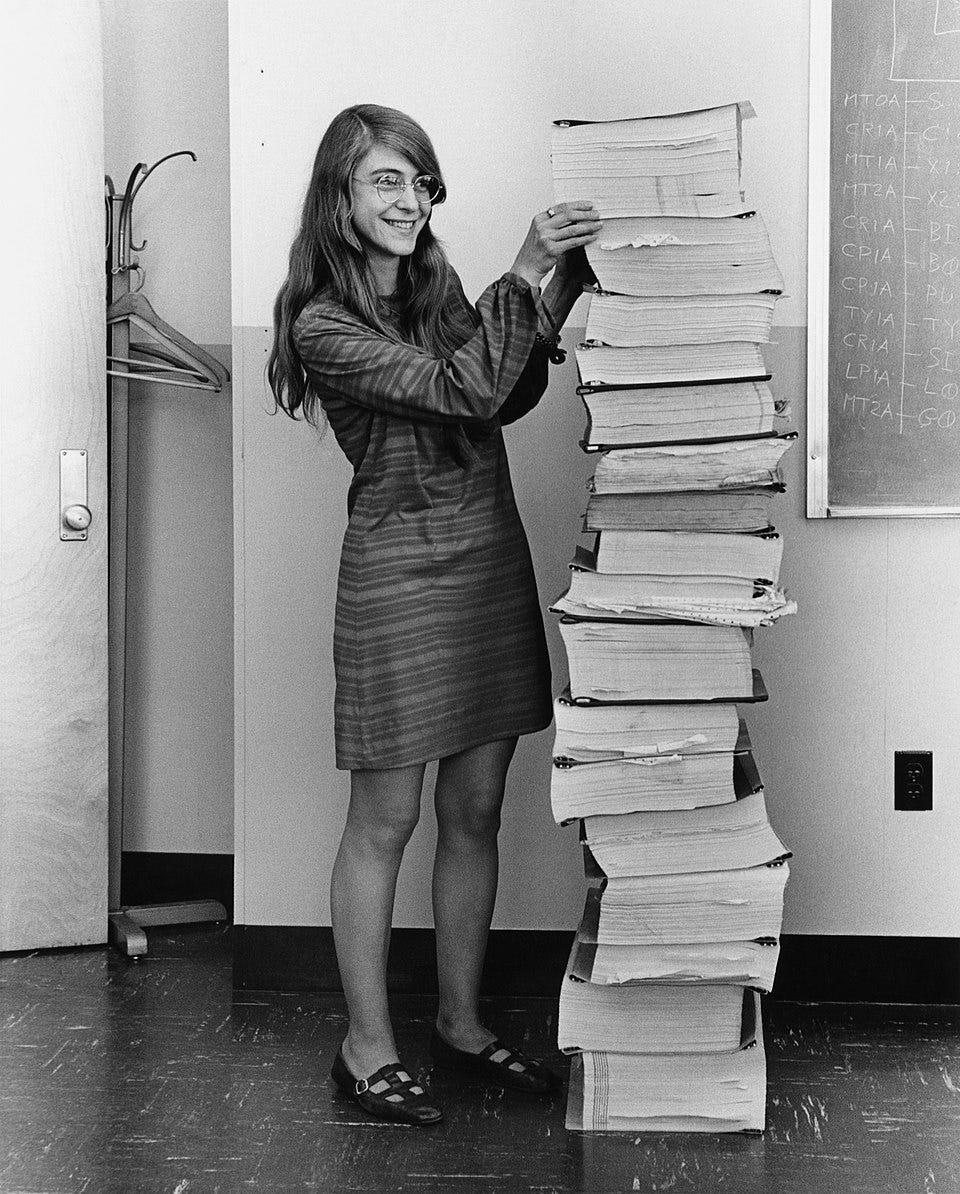

Margaret Hamilton : Apollo and Software Engineering

Margaret Elaine Hamilton (née Heafield; born August 17, 1936) is an American computer scientist. She directed the Software Engineering Division at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, where she led the development of the on-board flight software for NASA's Apollo Guidance Computer for the Apollo program. She later founded two software companies, Higher Order Software in 1976 and Hamilton Technologies in 1986, both in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Wikipedia

Oral History 2017 (Video 3h3m, Transcript 47 pages)

Gemini Summary

A trailblazer in the field of software engineering, Margaret Hamilton's career is a testament to her innovative thinking and unwavering dedication. Born in Paoli, Indiana, in 1936, Hamilton's early life in the Midwest was shaped by a family that valued education, arts, and music. She excelled in mathematics, particularly abstract math, which she later found to be connected to philosophy during her studies at Earlham College.

Hamilton's first significant foray into the world of computing was at MIT, where she worked for Professor Edward Lorenz on weather prediction programs. It was here that she learned to program the LGP-30 and later the PDP-1, developing a hands-on, problem-solving approach that would define her career. Her subsequent work at Lincoln Laboratory on the SAGE air defense system further honed her skills and instilled in her the importance of software reliability, a principle that became central to her work.

In the early 1960s, Hamilton joined the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory (now Draper Laboratory) to work on the Apollo program, a decision that would cement her legacy. She was part of the team responsible for developing the onboard flight software for the Apollo spacecraft. Faced with the immense challenge of ensuring the software was "man-rated"—meaning a person's life depended on its flawless operation—Hamilton pioneered new techniques and methodologies. She led a team that developed the systems software, which managed the complex interactions between different programs and the astronauts.

Hamilton's foresight and meticulous attention to detail were critical to the success of the Apollo missions. A notable incident occurred during the Apollo 8 mission when an astronaut inadvertently selected a pre-launch program during flight, a scenario Hamilton had anticipated but was initially told was impossible. Her insistence on creating a program note to address this possibility proved invaluable. Another pivotal moment came during the Apollo 11 lunar landing, when the guidance computer was overloaded with data. The error detection and recovery software Hamilton's team had developed allowed the system to prioritize critical tasks, enabling a successful landing with seconds to spare.

It was during her time on the Apollo project that Hamilton coined the term "software engineering" to legitimize the field and emphasize the need for a disciplined, systematic approach to software development. After the Apollo missions, she continued her work on Skylab and the Space Shuttle, and her research on error prevention led to the development of a theory of control based on a set of axioms. This work formed the foundation for her later ventures, including the creation of the Universal Systems Language (USL) and her companies, which focused on a "development before the fact" paradigm to create highly reliable software systems. Through her groundbreaking work, Margaret Hamilton not only helped put a man on the moon but also laid the foundational principles for modern software engineering.

The next Oral History is with a giant of software and computer languages, but the interview focuses on … chess.