Wafer Scale - Trilogy Systems: Part 2

The demise and afterlife of the first Wafer Scale startup.

In Part 1 we saw how Trilogy Systems was founded by Gene Amdahl in 1979 and went on to raise over $275m (c$830m in 2024 dollars) in funding to build ‘IBM plug-compatible’ mainframes. In 1983, the company revealed the ‘breakthrough’ technology it would use to overtake IBM: Wafer-Scale Integration. In place of the modules IBM used in its mainframes, each with 100 smaller chips and other components, Trilogy would use complete 2.5-inch silicon wafers.

Readers will have guessed, from the fact that there are no Trilogy ‘Wafer Scale’ machines (even in museums!), that Trilogy failed in its mission to build its revolutionary mainframe designs. So in Part 2 of the story of Trilogy, we’ll see how and why the company failed.

In a section for paid subscribers at the end of this part, we’ll reflect on what lessons can be learned from the story of Trilogy.

''They thought that with me there,'' says Amdahl, ''it wasn't really risky.'' But it was. ''It was risky for reasons I hadn't originally known how to evaluate, and in retrospect can't fully evaluate either,''

Gene Amdahl on Trilogy Systems

Trilogy raised over $275m in funding from venture capital ($85m), private investors ($55m), major computer makers ($80) including Honeywell-Bull, Sperry, and DEC, a 1983 Initial Public Offering ($55m), and a large portion of Gene Amdahl’s personal wealth. Computer makers' investment reflected their hope that they could use Trilogy’s Wafer Scale technology in their own machines.

In 1983 the company shared some details of what each of its wafers would contain.

Trilogy's chip, which he· describes as "like a macrocell-type of array, " is like a gate array. It consists of a number of transistors that can be put together in different groupings. It will have from 20,000 to 40,000 gates, considerably more than the largest bipolar gate array now available, one with 2,500 gates. That one measures a quarter-inch on a side and is only now going into production. The gate array that IBM uses in its 3081 has 700 gates. Amdahl Corp. 's has some 400. So the Trilogy chip could be the equivalent of 100 Amdahl Corp. chips.

When compared to its competitors, Trilogy’s machines would be faster - due to the shorter distances between components, more reliable - due to fewer error-prone wiring connections and the claimed ability of a wafer to ‘fix itself’, and much cheaper:

Trilogy figures its machine will weigh about a third of the Amdahl 5860, largest of that company's stable, and be smaller than IBM's fastest current model. The target manufacturing cost for 1986 is $500,000 per MIPS, thought to be a fourth of Amdahl's manufacturing cost and less than half of IBM's.

If Trilogy could get its technology working as promised and its machines to market, it would have a huge opportunity to revolutionize the lucrative mainframe market.

Mainframes Abandoned

But along with the promise and ambition, Trilogy had problems. Rather than partner with Fujitsu, as his previous company Amdahl Corporation had, Gene Amdahl decided Trilogy would make the wafers itself. So the company needed to build new fabs, develop its new Wafer Scale technology, and create a new IBM-compatible mainframe design. To do this it needed to create much of the technology and tools it would use. It was all too much and the company never gelled. Amdahl later commented:

The parts of the organization never seemed to mesh precisely. Engineers didn't develop that second-nature reliance on one another that for Amdahl marks a successful technology company. Instead employees galloped off in all directions, painting their own projects as essential and demanding reinforcements. The organization grew bigger and more unwieldy by the month. Like tunnels started from both ends that fail to meet in the middle, the separate projects never cohered into a whole.

And Gene Amdahl himself was distracted. Early on he was involved in an accident while driving his Rolls Royce in which a motorcycle rider was killed. A lawsuit followed which, while settled out of court, distracted him from running the new company. Then Cliff Madden, one of Trilogy’s three co-founders was diagnosed with a brain tumor early in 1982 and died later that year.

Even as the company started to reveal details of its new technology, its schedule started to slip. The original plan had been to bring Trilogy’s mainframes to market in 1984. That was first postponed to the third quarter of 1985, then to the fourth quarter of 1985, and then to 1986. Finally, in mid-1984 the company announced that it would not be shipping its new machines until 1987.

With the announcement of the last delay came confirmation from Trilogy that the company didn’t have the financial resources to finish its planned mainframes:

…, the company has the resources to continue its production plans through the third quarter of 1985 and is presently reviewing various financial sources to prepare a financial plan beyond that date; the new financial plan should be completed within 90 to 120 days,…

No soothing words from the company - a spokesman stated that this was ‘not the result of any underlying technological problem’ - could disguise the fact that Trilogy was in trouble.

How much money would Trilogy need to get its mainframes to launch? Losses were running at tens of millions of dollars per quarter. Even with around $100m in the bank Trilogy would need to find backers to provide an extra $100m-$200m.

But by now Trilogy’s credibility was gone. Unsurprisingly things began to unravel. In June 1984 Computerworld revealed that Trilogy had abandoned its plans to make mainframes, running with the headline:

Trilogy kills plan to get into the mainframe business

Reporting that:

CUPERTINO, Calif. Trilogy Ltd last week discontinued its attempt to develop a large-scale, IBM-compatible computer based on wafer-scale integrated circuits.

…

In a terse statement released last Monday, the company said the termination was a result of a comprehensive review of the project and "the anticipated competition in the computer marketplace."

The abrupt change of direction was a blow for Trilogy’s investors and employees, but perhaps most of all for Gene Amdahl, whose reputation had been central to Trilogy’s proposition. Amdahl’s emotional comments were accompanied by - probably unsurprisingly - an element of denial:

I would be less than candid if I did not say that it is extremely disappointing and sad for me to give up on our large computer system …

Even in defeat, Amdahl expressed the hope that his four-year-old company would be able to mount a new challenge to "IBM's dominance" of the large-systems industry, perhaps as early as 1988.

It was not to be.

Wafer Scale Abandoned

Amdahl and Trilogy’s management tried to make the best of a bad situation. If Trilogy couldn’t get its mainframes to market then maybe there was some value in its technology, particularly its much-heralded Wafer Scale Integration.

Sperry Corporation, which had invested $42m largely to get access to Trilogy’s Wafer Scale and Computer-Aided Design technology, tried to put on a brave face by saying that the company still planned to use Trilogy’s Wafer Scale technology in a future Sperry mainframe. Not everyone was convinced though, with one analyst - quite reasonably - responding that:

If the technology wasn't going to be good enough for Trilogy's mainframe for several years to come, why should it be good enough for other company's mainframes?

By now it was common knowledge that the company had had problems with one of the key challenges of getting its Wafer Scale technology to work. If a complete wafer contained the equivalent of 100 of the chips used by Amdahl or IBM then, running at the same speed, it would generate the same heat as all those chips but in a smaller space. Dissipating all that heat was not straightforward.

The New York Times reported in July 1984 that a test the previous year had ended disastrously:

In December, at a gathering of Trilogy executives to test a prototype of the big chip, the giant circuit shorted out, apparently because two microscopic wires crossed. Heat built up in the chip's circuits, turning the entire block of silicon a fiery red.

Trilogy now claimed that it had solved these problems and that the technology would be working in 1986 or 1987. But the delays only confirmed that the company was having further problems.

Gene Amdahl, many years later, in his Oral History interview with the Computer History Museum, would outline one of the issues the company was struggling with:

We had to have very heavy wire deposited, heavy metal deposited on it to make it very good conducting. That meant that we had to keep the metal deposition on it longer, it would heat it up more, and so the metal didn’t contract at the same rate that the chip did. And so, it pulled the wiring loose, and so we finally solved that problem.

We found that if we put a little layer of nickel on before we put the metal on, the nickel bonded better and that held it. So we solved that problem ..

But there were even more issues:

… were still getting more errors due to leakage of chemicals in the various process steps. So we had to adjust the masks a little bit. But each turnaround took eight months.

Carlton Amdahl, Gene Amdahl’s son and a co-founder of the firm, left in June 1984. He painted a bleak picture to the New York Times of the difficulties he had faced at Trilogy:

''It's not like we made mistakes, it's just that we didn't know enough about the issues we would face,'' he said in a recent telephone interview. ''It got so complicated that you could put the smartest people in the world on the project and they would give you gut feel rather than fact. There just wasn't an appreciation of how hard it was going to be,'' he added. ''I would wake up in the middle of the night in cold sweats, thinking about what we were doing wrong. All I was dreaming about was the computer design and how the pieces fit together. I would dream schematic diagrams of the machine.''

Morale plummeted and there were reports of internal strife at the company as senior staff left and engineers disagreed with the approach being taken by the founders:

others at Trilogy agree that infighting developed, with the engineers allied against the Amdahls.

By now Gene Amdahl estimated that it would take two more years and all the company’s remaining funds to fix all the issues with its technology.

Without Trilogy’s mainframe systems as a destination for its wafers, the company was dependent on external customers. Honeywell-Bull, Sperry, and DEC had all invested heavily to get access to Trilogy’s technology, but understandably, they were now less than enthusiastic about continuing to support its development.

So Trilogy had to abandon its Wafer Scale technology too.

In September 1984 the company appointed Henry Montgomery as its President and COO. Gene Amdahl was clear that he was appointed to make the best of what was left of Trilogy, saying to the New York Times:

''Mr. Montgomery's experience has largely been in finance and in helping companies who have gotten into financial difficulties,'' … ''We expect him to function in that role here, and to determine how best to maximize the use of our resources.''

Soon what was left of the company’s operations was being sold off. In September 1985 the Cupertino Fab was leased to startup Saratoga Semiconductor, which used it to make Static RAMs. Saratoga went bankrupt in 1989. In June 1986 DEC paid $10m for the part of Trilogy responsible for new interconnect and packaging technologies with almost a third of Trilogy’s remaining staff transferring to DEC.

ELXSI

Mainframes and Wafer Scale had been abandoned, and fabs and other key assets had been sold. Little was left of the original Trilogy business.

But Trilogy still had $70m in the bank. What to do with this cash? Trilogy’s investors told Gene Amdahl to find another business to invest in. In June 1985 Trilogy announced that it would use its remaining funds to buy a majority stake in, and then merge with, Elxsi Corporation.

Elxsi had originally planned to make machines that were ‘plug compatible’ with the popular DEC VAX 11/780 minicomputers but more powerful than any of DEC’s machines.

Like Trilogy, Elxsi planned to use innovative technology to support this assault on a well-established and much larger competitor. Where Trilogy had Wafer Scale Integration, Elxsi had a range of techniques including multiprocessing, with its computer containing up to ten CPUs.

And like Trilogy, Elxsi had run out of money.

Elxsi at least had real products - its System 6400 had launched in 1983. The merger with Trilogy provided the cash needed to get its next product - the System 6420 - to market.

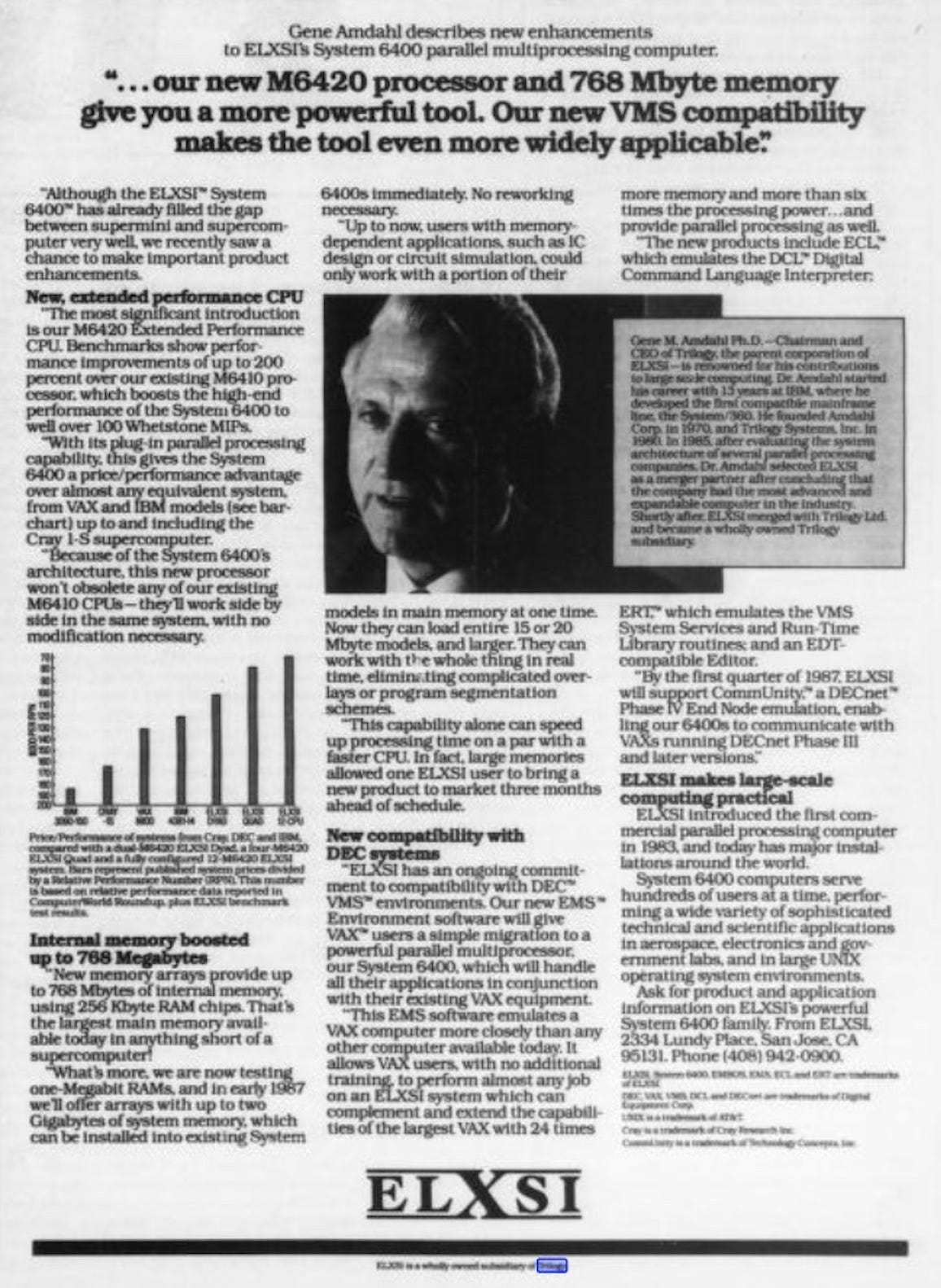

The Trilogy merger also brought Gene Amdahl’s public endorsement and his picture and commentary appeared in a September 1986 launch advertisement for the System 6420.

But again it was not to be. The press was already skeptical even at the time of the Amdahl-fronted launch of the 6420. CNN reported that:

Business trouble comes in all sizes, rarely bigger for one man than Gene M. Amdahl's quarter-billion-dollar debacle with Trilogy, a company he founded to beat IBM at its own game. … But as misery loves company, his violent, front-page, heroic disaster has joined hands with the ordinary, grinding, slow-death trouble at an outfit called Elxsi.

Trilogy took on the name of its merger partner. By 1988 the company was reported as having 80 customers and 100 CPUs installed. It was not enough though, and Elxsi’s “grinding, slow-death” came to a conclusion in 1989 when it left the computer market.

Gene Amdahl left Elxsi in 1989 but had already started a new IBM plug-compatible mainframe business, Andor Systems, in 1987. Again Andor ran into difficulties and was declared bankrupt in 1995.

It wasn’t quite the end of the Elxsi story, though. By now the company had large tax losses that could be valuable in the right hands so in 1989 it was sold to someone who had plans to make use of them:

In 1989, a group led by Connecticut investor Alexander “Sandy” Milley bought the company as a vehicle for leveraged buyouts. The plan was to buy profitable companies with good cash flow and use Elxsi’s tax breaks to maximize the return to investors.

What did the ‘new Elxsi’ buy? Restaurants and a maker of drain pipe inspection and repair equipment. Trilogy’s original investment had - literally - gone down the drain.

Trilogy - Amdahl’s Verdict

So we over expanded, we should not have done it on semiconductors.

It wasn't that the technology couldn't be done; it was that we had bitten off more than we could chew. The technology was so advanced it required something new in almost every area of supporting technology.

Gene Amdahl

It was too much. Designing a new IBM-compatible mainframe computer from scratch, building two fabs, and, most of all, developing the technology needed to implement Wafer Scale Integration.

The demise of Trilogy took a very personal toll on Amdahl. The firm didn’t have his ‘name on the door’ but it was still very much his company, saying after its demise:

… so many people invested because I had my name on it. I feel responsible. I get haunted by guilt feelings. I sort of cringe when I see my acquaintances. That was a bruise — a real bruise that hasn’t healed yet. And I don’t know that it ever will.1

In the afterword for paying subscribers, we reflect on what lessons can be learned from the rise and fall of Trilogy systems with brief appearances by Cerebras and Anamatric.