Cash, Canadians and CPUs : Intel's 'Lost' Early Microprocessor

The story of Microsystems International and the Intel 4005

ECTEK, DISTEK, ESSCOTEK1. Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore soon discarded these names and others. Moore Noyce Electronics was rejected as it sounded too much like more noise. N.M Electronics was used on the first paperwork but was rejected as being too bland. Instead, they chose ‘Intel’ which Noyce thought ‘sounded sort of sexy’.

Raising money was much less problematic than finding a name. Noyce and Moore had great connections and a track record at Fairchild. Helped by Arthur Rock, they quickly raised money, first in July 1968 and then again in September 1968. The company grew quickly until it was able to sell shares to the public in 1971.

There is, however, a key part of Intel’s early financial history that is sometimes omitted. It involves a little-known Canadian company with global ambitions.

By the middle of 1970, Intel had been up and running for almost two years, but was still loss-making. At this stage, it was just one of several new firms looking to prosper in the growing market for integrated circuits.

Thousands of miles to the East, in Ottawa, the Canadian federal government decided that it didn’t want Canada to miss out. There was already one company close by that was already making integrated circuits. Northern Electric, a subsidiary of Bell Canada, had a manufacturing facility at its Advanced Devices Centre near Ottawa. In March 1969 with C$48m (roughly $44m) of government funding, the center was transferred into a new company ‘Microsystems International Limited’ (MIL). MIL also raised over C$20 in a public offering of shares and had C$10m in bank facilities.

Armed with this cash (over $700m in 2022 terms) MIL set off on a period of rapid expansion. It built facilities in Germany and Malaysia. It also sought out leading technology partners around the world, including Intel.

Robert Noyce saw an opportunity. He told MIL “pay us our net worth and we’ll all teach you what we know”. MIL and Intel signed an agreement on 2 July 1970. MIL would pay Intel $0.5m upfront and a further $1m in 1971 depending on yields. Royalties could add even more to Intel’s income.

The fees were relatively small for MIL but were significant for Intel. $1.5m was four times Intel’s revenue in 1969. The company was growing quickly but it was still making losses, with a loss of $1.9m for the year. It also faced the need to finance building a new combined headquarters and manufacturing plant which would cost millions of dollars.

Noyce saw that MIL also helped to solve another problem. Customers liked its integrated circuits but were nervous about relying on such a new startup. What would happen if Intel’s modest Fab burned down? What if the company failed? Having a partner producing identical components would help reassure customers. That the partner was well funded and backed by the Canadian government, no less, was even better.

But although the deal looked great for Intel’s finances and marketing it was decidedly unappealing to its manufacturing management. Which meant Andy Grove.

Grove was focused on producing the 1103 integrated circuit, the first commercially available Dynamic Random Access Memory, and the key product in Intel’s product line. It would be fair to say that he was struggling to produce the 1103 as conditions in Intel’s sole mountain view fab were chaotic. According to Leslie Berlin’s biography of Robert Noyce.

Ovens were used to reheat food for potluck dinners. Roof timbers cracked because the roof was overloaded with process equipment. Sump pumps flooded. An alloy furnace blew its cap so often that employees began a contest to predict how far the cap could travel. … More than one fab employee recalled late-night parties that ended only when the security guard barked, "All the drunks, out of the building!"

To make things worse, to ensure that MIL was successful in getting production of the 1103 working and so earn the licensing fee, Intel had to send its best employees to Ottawa. Grove later said about the loss of key staff:

“I would have to improve yields without a manufacturing manager or chief technologist.”

Grove was only managing to produce one or two working 1103s per wafer. When he heard about the proposed MIL deal, he argued against it. Finally, in the middle of 1971, as Intel was preparing to send engineers to Ottawa to work on the 1103, Grove confronted Noyce. Quoting Berlin again:

He went into Noyce's office and found him there, talking with Moore. Grove immediately began arguing against the plan "as aggressively as I was capable--which was very." He insisted that Intel could not increase the 1103 yield, maintain the fab, satisfy customers, and find new prospects with half the staff in Canada. "This will be the death of Intel!' he yelled at one point. "We'll get the $1.5 million, and then we'll sink."

Noyce let Grove finish and then replied:

We have decided to do this. You need to put your energies into figuring out how to do this.

Grove left with, as he described it, “his tail between his legs”.

But it wasn’t just memory chips that MIL bought the rights to manufacture.

In the course of working on the agreement with Intel, MIL’s engineers discovered that Intel was working on something exciting: a microprocessor - a chip that placed all the main control functions of a computer on a single integrated circuit. The chip was being developed for the Japanese calculator manufacturer Busicom and would eventually become known as the 4004.

There was one problem though. Intel didn’t own the rights to the 4004 design, Busicom did.

Hoff had a solution though. When mapping out the 4004 he understood that its design was pushing the limits of what it would be possible for Intel to manufacture. So he developed a fallback in the shape of a simpler design.

The alternative would work with standard memory parts. It had a smaller number of registers. It wouldn’t have an on-chip stack. This simpler microprocessor would become known as the 4005.

So Intel offered the 4005 to MIL who, ambitious to expand their product line, were happy to accept.

The relationship with Intel initially worked well for MIL. With Intel’s best engineers working to set up the plant in Ottawa they were soon producing second-sourced versions of key Intel products, including the 1103. MIL employees said that they ran the 1103 process better than Intel and Moore commented that they were probably right. Intel earned the licensing fees in full.

Intel went public in October 1971. The ‘extraordinary’ (to use the accounting term) income from MIL took Intel from a loss of $1m to a profit of $0.4m.

By December 1971 it was clear that, due to the hard work of Federico Faggin, Masatoshi Shima and others, the 4004 and its companion chips would work. The 4005 would no longer be needed and so Intel stopped all work on its development.

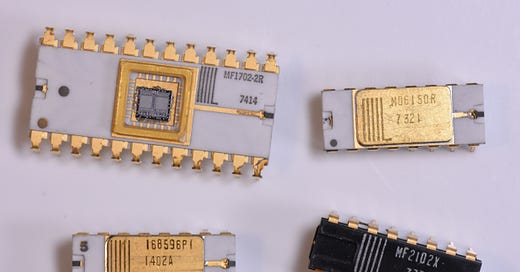

But MIL, who didn’t have rights to the 4004, continued work on the 4005. It was renamed the ML4005 and then (as the ‘5’ really digit only made sense in relation to the 4004) the MF7114.

Intel’s commitment to helping MIL finished at the end of 1972.

Andy Grove had succeeded in keeping production of the 1103 working at Mountain View and yields were getting better. Now Intel was starting to make 3-inch diameter wafers, dramatically increasing the number of chips per wafer. MIL tried to follow, only to see their yields collapse catastrophically. This time they had no Intel engineers on hand to help them implement the new process. Having the secrets of one generation of chips was no guarantee of success in the next.

MIL pressed on with the development and production of the MF7114. The final design of the MF7114 stands in contrast to the 4004. The MF7114 had a 4-bit accumulator and a single ‘overflow’ bit ‘on-chip’. Other ‘registers’, including eight 4-bit data registers and eight 12-bit address registers, were implemented using the first 16 bytes of main memory. In an approach reminiscent of the later and wildly successful 6502 microprocessor, used in the Apple II, this allowed shorter instructions when accessing these ‘off chip’ registers when compared to other memory.

Consistent with 12-bit addresses the MF7114 could address 4,096 half-byte nibbles. Unlike the 4004 it had separate data and address buses and was housed in a package with 24 pins, a major improvement on the 4004’s restrictive 16 pins.

MIL also designed two companion chips, a Read Only Memory and a Random Access Memory. Together they were marketed as the CPS/1, a complete computer system.

Before long Intel was powering ahead. It had revenues for 1974 of $134m and net income of nearly $20m. It was well on the way to becoming one of the world’s leading semiconductor manufacturers. The 8008 would lead to the 8080 and then to the lucrative x86 series of microprocessors.

But by the time the MF7114 was launched the world was moving on from 4-bit to 8-bit systems. MIL acted as a ‘second source’ for the Intel 8008, launched in April 1972, which was much more powerful and flexible. Despite growing sales MIL was losing money and major job cuts were implemented in Fall 1973. At the same time MIL abandoned the 7114 in favour of its version of the 8008.

MIL was soon powering down. It closed in June 1975 having lost most of the grants and loans made to it by the Canadian government. Its collapse was a scandal in Ottawa.

What can we learn from this? We don’t know precisely how far Intel had progressed with the design of the 4005. It doesn't seem likely that Intel’s Federico Faggin - who built the 4004 - did much, if any, work on the project. Credit then to the MIL engineers who built a working microprocessor from the high level designs that they are likely to have received from Intel.

It would be easy to juxtapose the entrepreneurial Silicon Valley startup against its lavishly government-funded Canadian partner.

Easy but possibly wrong. MIL had too much money and got lots of things wrong. It may have suffered from dishonesty amongst its staff. However, it wasn’t lacking in ambition and was smart enough to recognise Intel as a highly desirable partner. Instead, maybe it’s better to recognise just how difficult manufacturing leading-edge integrated circuits was.

Further Reading

Zbigniew Stachniak has produced an excellent paper ‘The MIL MF7114 Microprocessor’ which has lots more information on the story and on the 7114 itself.

Also, for more detail on the 7114 and the CPS/1 there is the York University Computer Museum website.

An emulator only seems to be available on request but there is lots of detail in the manual and the original 7114 documentation linked from the website.

Photo Credit

By Feinhals pengo - Own work,

CC BY-SA 4.0

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=95745359

ECTEK stood for ‘Electronic Computer Technology’, DISTEK for ‘Digital Slid State Technology’ and ESSCOTEK stood for ‘Electronic Solid State Computer Technology’. A fuller list of the names considered is available here. It’s interesting how ‘Solid State’ and ‘Tek’ as an abbreviation for ‘Tech’ have disappeared from common use.

MikroTik seems to be leftover as the last Tek style abbreviation. I can only assume 'tik' is the Latvian version of 'tek'.

They are the only ones left who sell new/modern WiFi-less home routers, it seems. Some routers are even MIPS based, like mine.

I featured your publication in the issue #124 of Embedsys Weekly. Thank you very much for writing this newsletter https://embedsysweekly.com/124-tribute-to-wolfgang-denk/