Today, Nvidia grabs the headlines as the most valuable company in the world, with a market value of over $4 trillion. Over the last few years tech giants Alphabet, Apple and Microsoft have each also vied with each other for that title. Today each of these firms has a market value of more than $3 trillion.

If we go back in time far enough though, one firm stood alone as the most valuable technology company in the world. It held this crown for many years. Its dominance was built on its position as the leading supplier of both hardware and software to a majority of the leading companies in the US and more widely. That company was, of course, International Business Machines also known as IBM or ‘Big Blue’.

In fact IBM wasn’t just the most valuable tech company it was, for a while, the most valuable company in the world.

IBM today is a shadow of its former self. Its dominance long gone, it has defended its, highly profitable, place as a supplier of legacy mainframe systems and software, but other than that the business today is seemingly mostly focused on selling consulting services.

In reality, today’s, apparently much diminished, IBM is still a big company: it’s just behind AMD with a market value of around $230 billion.

This begs some questions. If it was so dominant, then how big was IBM at it’s peak? How does that peak compare with today’s tech giants? In the rest of this post we’ll try to answer these questions and to put IBM’s size and dominance into context.

So how big was IBM?

Even at its peak IBM’s market value, adjusted for inflation, never reached the heights of today’s biggest tech firms. In 1985 IBM had a market value of around $90 billion (around $270 billion adjusted for inflation in 2025 dollars1) ahead of Exxon and General Motors in the number two and three spots. 1985 is perhaps one of the last years when IBM was generally seen as being preeminent.

Note that a simple web search for IBM’s market value gives the wrong answer. For example this article from Motley Fool hosted on the Nasdaq website quotes a value of ‘around $30 billion’. This is wrong. Coming up with the actual market value is more complex than might be expected and the reason why this estimate and others are wrong is revealing of what happened to IBM in the years that followed its dominant period. More on this in a future post.

Just one year earlier, on 1 January 1984, AT&T, IBM’s only real rival for the title of biggest technology company, had been broken up, with seven ‘Baby Bells’ - local telephone companies - spun off into separate companies. The AT&T that was left behind was much smaller and was less able to fund technology research at its Bell Labs subsidiary.

Today AT&T and those ‘Baby Bells’ have largely been reassembled into ‘modern’ AT&T and Verizon, but these two firms have a market value of less than $400 billion. Bell Labs, now a shadow of its former self, was eventually acquired by Nokia in 2016.

IBM escaped AT&T’s fate, and survived multiple antitrust actions that attempted to break it up.

Given its dominant position at the time, it’s remarkable that IBM’s 1985 inflation adjusted market value of around $270 billion barely squeaks into the list of 50 most valuable companies in 2025. On the day I checked this, IBM’s inflation adjusted market value would place it a little behind Coca-Cola and General Electric. It’s a long way behind Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple and their peers with their multi-trillion dollar valuations.

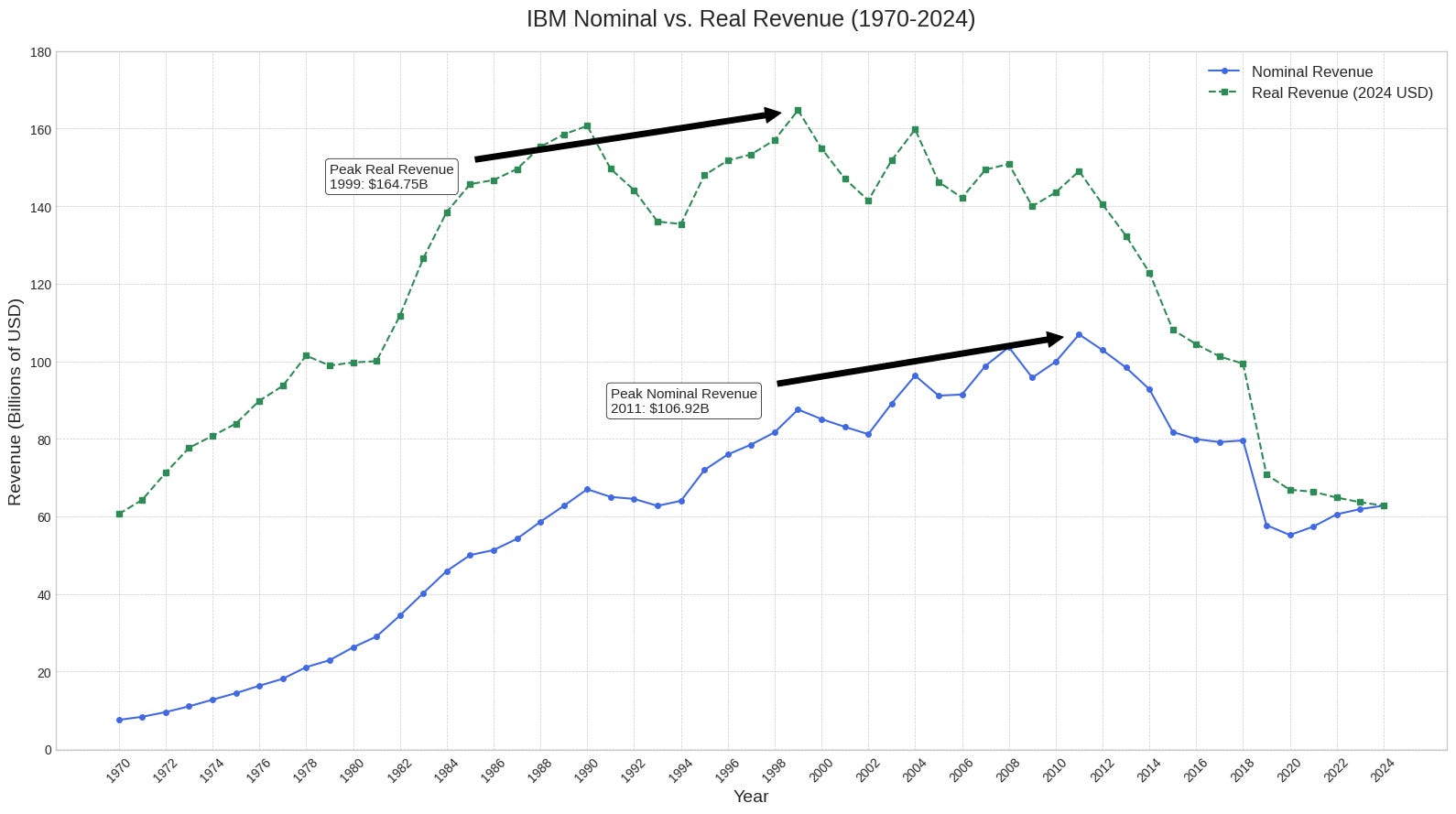

It’s clear then that big companies have, in general, got a lot more valuable. Market value isn’t the only measure of size, though. What about revenue? Here the comparison is a little closer.

In 1985 IBM had revenue of slightly more than $50 billion, or adjusted for inflation, around $150 billion. This compares with revenue in 2024 for Microsoft of $245 billion, Alphabet $350 billion, Apple’s $391 billion, and only $60 billion for Nvidia.

What about net earnings? IBM reported net earnings in 1985 of $6.56 billion or around $20 billion adjusted for inflation. Microsoft’s was $88 billion, Alphabet’s $100 billion, Apple’s $93 billion and $30 billion for Nvidia.

One final measure of IBM’s size; number of employees. In 1985 IBM had 405,000 employees worldwide. This compares to 228,000 at Microsoft, 164,000 at Apple, 183,000 at Alphabet and less then 30,000 at Nvidia in 2024.

So in revenue terms IBM was smaller but in the same ballpark as today’s giants (with the exception of Nvidia which is something of a special case). The big modern tech companies are much more profitable though.

One measure where IBM does rank above today’s tech giants is the extent of its presence across the breadth of the era’s technology markets. Mainframes? Of course, IBM was dominant. Minis? IBM had several offerings. Microcomputers? By 1985, IBM’s PC had became synonymous with the personal computer, although this wouldn’t last for long.

And in software, IBM didn’t just sell operating systems for all these machines. It sold compilers, databases and application software.

So how dominant was IBM in the markets in which it operated? Let’s focus on its most important market for many decades, mainframe computers.

In the 1960s the nickname given to IBM’s competitors tells its own story: the seven dwarves. Burroughs, Univac, NCR, Control Data Corporation, Honeywell, General Electric and RCA all made big computers that competed with IBM - sometimes known as ‘Snow White’ in this context - but none ever approached IBM’s scale. As GE (1970) and RCA (1971 with mainframe division sold to Sperry) left the market these competitors became known by the acronym ‘BUNCH’. In the 1960s IBM typically had market share of between 70% and 80%.

Then in the 1970s IBM faced competition from so-called ‘plug compatible mainframe’ (or PCM) manufacturers; manufacturers who made machines that were hardware and software compatible with IBM’s machines. Amdahl Corporation, led by Gene Amdahl, who had been chief architect of IBM System/360 mainframe in the early 1960s, gained double digit market share in the early 1980s.

Fujitsu and Hitachi (plus to a lesser extent NEC and Toshiba) in Japan also made ‘plug compatible’ mainframes and their technology was licensed to a range of other firms including National Advanced Systems and Itel Corporation in the US. There was competition in Europe too including ICL in the U.K. and Siemens and Nixdorf in Germany.

All this competition saw IBM’s mainframe market share drop to between 60% and 70% at the start of the 1980s.

So how does all this compare with modern tech giants? The breadth and depth of IBM’s presence is unrivalled today. Microsoft probably comes closest with its dominance of PC operating systems, business productivity software, plus its place as a major player in the cloud and gaming. Google has worldwide search market share of almost 90%. Apple dominates the market for high-end phones and like IBM controls almost all the ‘stack’ for its machines. It comes nowhere near having IBM’s market share in its biggest market though. To compensate, though, that market is much, much bigger and Apple is much more profitable than IBM was, even at its peak.

In our next post we’ll look at how and why IBM’s dominance started to crack, as it barged into the new market that would create Apple and Microsoft - the personal computer - only to find itself humbled.

https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1985?amount=1#:~:text=Value%20of%20%241%20from%201985%20to%202025&text=%241%20in%201985%20is%20equivalent,of%20%242.00%20over%2040%20years.