Inmos and the Transputer - Part 2 : Politics and Processors

The last days of Inmos and the Transputer

Inmos’s fate would likely be determined by concerns about national security. That link, between semiconductor manufacturing and national security has, of course, become a central topic of political discourse in 2023.

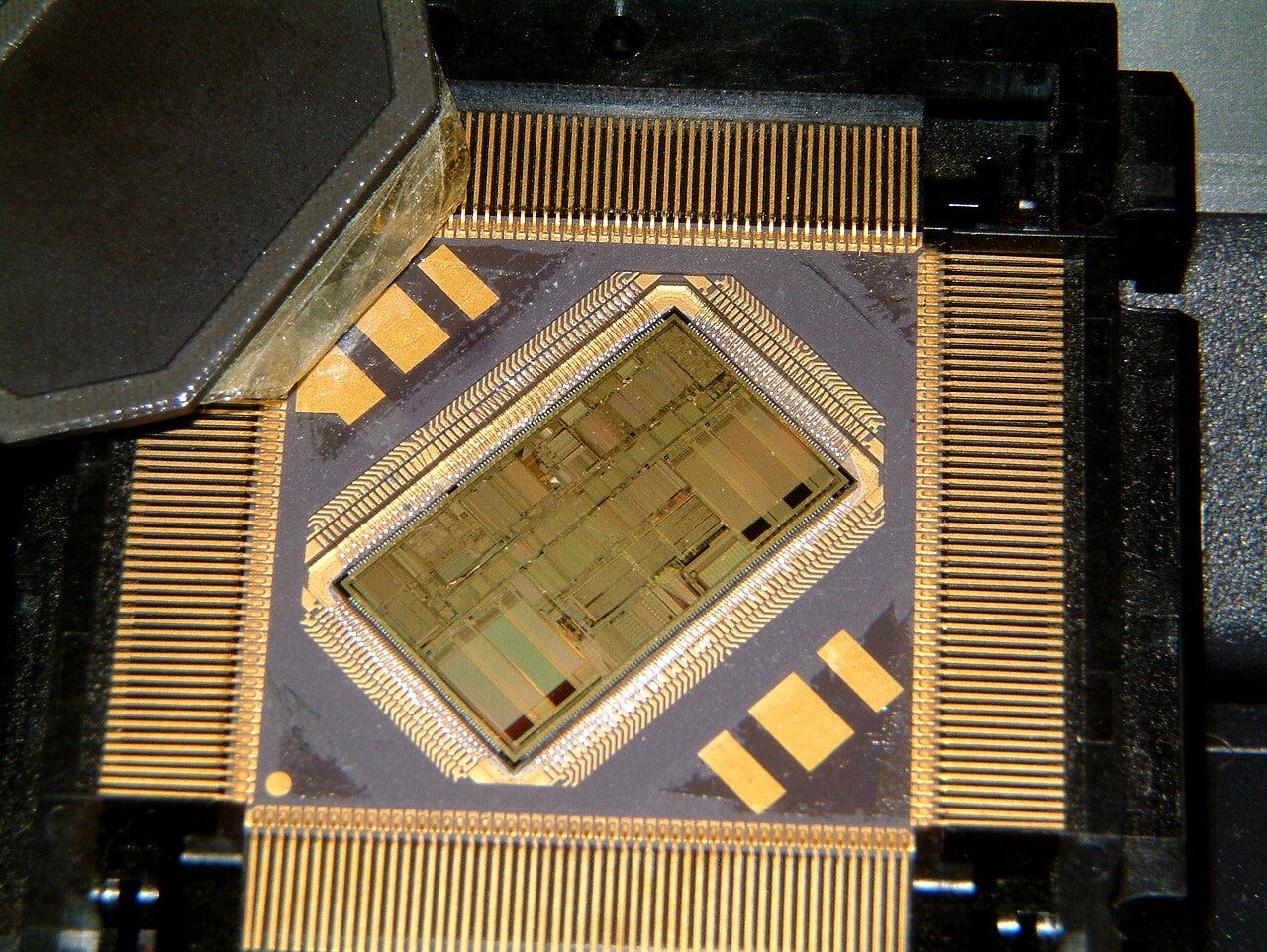

In Inmos and the Transputer - Part 1 we saw how Iann Barron and Richard Petritz set up Inmos. The company quickly built the capability to design and build leading edge Static and Dynamic Random Access Memory chips and an innovative new microprocessor, the Transputer.

In this post, we’ll look at the turbulent later history of Inmos, consider some lessons from the saga and hear from some of those involved.

The final post in this series will look at how the Transputer was used in practice and at the enduring legacy that Inmos has left behind.

That legacy is very much still alive! That post will feature Graphcore, Xmos, Nexperia and Nvidia and the latest controversy around Inmos’s Newport Fab.

Mrs Thatcher

Inmos had been funded by a British Labour government, in the form of $100m investment by the state backed ‘National Enterprise Board’. But, soon after Inmos launched, the political environment in the UK changed radically.

In 1979 Margaret Thatcher became prime minister. By the early 1980s her government had set in motion a program of ‘privatisation’ of previously state-owned industries. Telecoms, electricity generation and many others were to be sold to private investors.

Under her government the National Enterprise Board, now renamed as ‘British Technology Group’ or BTG, had no future as a state backed investor in private companies. What’s more it was reported that she repeatedly expressed her hostility to the investment it had made in Inmos.

In the early years of the Thatcher government, Inmos was loss-making and needed further support from BTG. Coverage of Inmos in the British press was generally negative. In August 1982, ‘The Economist’ piled into the company:

'Inmos', the semiconductor company three-quarters owned by the government's high-technology holding company - the British Technology Group (BTG) - is on the scrounge for yet more money. BTG estimates that Inmos, which had already had £85 million from the taxpayer, will need another £10 million-£15 million next spring. Officially this is to cover a gap in its working capital. Unofficially, Inmos wants the loot to tart up its balance sheet into something the City could swallow without a liquid laugh.

The Thatcher government’s agenda was clear. Inmos would be sold.

Atari, GE, AT&T, Next – Finding a Buyer

Finding a buyer would be a tortuous process.

Jack Tramiel’s Commodore was early to express an interest. Two British semiconductor companies – Ferranti and Plessey – that were reported to be interested in Inmos. Even Steve Jobs’s Next Inc was reported to be interested. Then there was interest from the British ‘General Electric Company’ (no relation to the American GE). None of these came to anything.

Finally, AT&T made a $78m offer for Inmos.

We can get a sense of the state of the debate about Inmos in in the UK at this time from this short TV programme from 1984.

Themes from this programme still resonate almost 40 years later. albeit with very different protagonists. Presenter Tony Bastable gives viewers some context for the sale of Inmos:

What would happen if AT&T bought Inmos? Well we think this is what would happen. They would buy it and we would then be denied that Transputer technology. Why? Because of the sensitivity of the Reagan government for high-tech computer secrets leaking out to our cousins in the Eastern Bloc countries. So sensitive are they that they frequently won’t allow that technology even to go to their allies…

So if the transputer gets into American hands we … may be denied the use of it.

Inmos’s fate would likely be determined by concerns about national security. That link, between semiconductor manufacturing and national security has, of course, become a central topic of political discourse in 2023.

In the end AT&T’s offer was rejected as ‘derisory’ by a UK government minister. Employees at the Inmos’s US facilities were reportedly unhappy at being absorbed into the US telecoms giant. So the AT&T bid fell through.

Mishaps and Progress

Whilst this search for a buyer went on the company continued to make progress, even in the face of operational mishaps. One notable example happened on Christmas Day in 1982. The supply of pure water that the company relied on at the Newport, UK, Fab was contaminated. The problem seemed to be with the resins that were used in the de-ionisation process. According to Barron:

What we had to do - and this was all across the holiday period - was to physically dig out all this resin and get another lot trucked in and loaded. Virtually everybody in the company, including me, had shovels, and was standing in these great big tin cans shovelling resin.

The result was that the Americans said, "These Brits don't know what they're doing. Get rid of them!". The semiconductor facility was taken away and put under the control of the Americans who were deemed to understand these things.

What had actually happened, as we found out three months later, was that on Christmas Eve the engineers at the local reservoir decided to celebrate. They were supposed to stay on site, so what they did was to dump 100 times the standard level of chlorine into the water supply, then go off and have a Christmas party. That chlorine totally ruined our semiconductor plant.

Despite these mishaps, the company did make progress. According to Barron, by 1984:

I had forecast that in that year Inmos would have a turnover of £150 million - which it did - that it would have a profitability of £12 million - I think we actually made £15 million - that the NEB would exit during the year, and that the company would be valued at £125 million. That is exactly what happened.

Thorn-EMI

Finally, in July 1984 British conglomerate Thorn-EMI agreed to buy the UK government’s 76% stake in Inmos for £124m.

Thorn-EMI was, in almost all most respects, an awful buyer for Inmos. It was already an odd collection of businesses including the EMI record company, home of the Beatles.

The sale came out of the blue for Barron:

It was quite sudden, totally unexpected and, from my point of view, very surprising. I was called up one day and told "There's this company that wants to buy you". I went to various meetings, the last of them at the Department of Industry offices in Victoria Street. It started about midday and went on until midnight at which point the deal was done.

Inmos needed cash, but none of the sale proceeds were invested in the Inmos business.

There was one flaw. The business plan said that in 1984 not only would the company be sold, but that it would be refinanced, because we knew at that stage we would want money put in to expand our business further. But there was no refinancing, and no money went into Inmos. The £125 (sic) million went straight to the Treasury.

So from that moment on we had no cash to do anything. We couldn't advance the technology in any way. We couldn't develop our memory products. It was not really Thorn's fault. They shouldn't have bought Inmos - it was a really stupid thing to do, and (Thorn-EMI Chairman) Peter Laister was ousted from that company within three months. Thorn did try their best to look after us. It was just that they didn't have the kind of cash that was necessary to fund and run a large-scale semiconductor company.

Thorn-EMI was, in almost all most respects, an awful buyer for Inmos. It was already an odd collection of businesses including the EMI record company, home of the Beatles. It had just tried and failed to take over UK defense contractor British Aerospace. The executives at Thorn-EMI knew very little about semiconductors. They were themselves under pressure from investors after a long period of indifferent performance. Thorn-EMI certainly wasn’t the patient long-term investor that Inmos probably needed to become successful.

Unsurprisingly, Thorn-EMI soon found out that they had bought more trouble that they had expected. According to the book ‘The Inmos Saga’ by Mick McClean and Tom Rowland:

Towards the end of 1984 and into 1985 it was slowly dawning on Thorn executives exactly what they had got themselves into. The company did not know much about semiconductors … No one in Thorn carried out any serious research on chip markets or on the possible future links with parts of Thorn.

That lack of knowledge soon had an effect on the company. According to Inmos co-founder Richard Petritz:

As is often times the case, when somebody buys a company, something changes. At some point, Thorn-EMI decided that they could run it better than the Americans, and I agreed to stay about a year, and I stayed a year. And at that time, the industry had turned down and they sort of panicked, and they gave up on a lot of things they were thinking. They put in their own management, John Heightly. All of my key guys, we were all basically fired at the same time — I think it was July 1, 1985. I was happy to get out.

Soon, Thorn-EMI itself found itself under further pressure from its shareholders.

SGS Thomson and the Transputer

So the inevitable happened and Thorn-EMI again looked for a buyer for Inmos.

In 1989, Inmos was sold to SGS-Thomson (now known as STMicroelectronics) then 50% owned by Thomson-CSF SA of France, 50% by Stet SpA, the Italian state holding company.

The sale of Inmos made it into a debate in parliament with an opposition Labour MP commenting in parliament when the sale was announced, that:

It is a matter of national interest that a successful, strategically important technology company remains in British hands and does not become a foreign subsidiary that will be dependent upon the whims of a foreign owner. We cannot allow Thorn-EMI's short-term market needs to decide Inmos's long-term future. To allow Inmos to pass into foreign hands will be a body blow to the whole of Britain's information technology industry.

But it was to no avail. The plea for a debate was rejected. The sale went ahead.

It would be hard not to see the irony in the fact that the ‘privatisation’ of Inmos would lead to its acquisition by a firm that was largely owned by the French and Italian states.

SGS-Thomson already made second sourced microprocessors for Motorola (68000) and Zilog (Z80). It now started talking up the prospects of the Transputer. A contemporary news report stated that SGS-Thomson …

… have been desperate to find a way in to the 32-bit microprocessor market: they now reckon that the Transputer could become the third most widely used microprocessor architecture on the world market after the Intel iAPX-86 and the Motorola 68000 in the early 1990s, taking a share of perhaps 10%, and that share would be worth almost $100m on current forecasts

So investment in the transputer would continue under SGS-Thomson’s ownership. There was one problem, though:

The Managing Director, Pasquale Pistorio, was very enthusiastic about the transputer. He thought it was an extremely good product and wanted to revive it. He was prepared to put a substantial amount of money in this. But there was a fundamental problem. No work had been done on the transputer in terms of implementation and design since about 1985, and this was 1989.

The next version of the transputer would be known as the T9000, It would be an ambitious upgrade that incorporated a five-stage pipeline, superscalar execution and a true high-speed cache. According to David May:

So essentially, it should have been a follow on from the T-800, and it got into the hands of a rather over-enthusiastic development team, in my view, which actually tried to speed it up in ways that took them into a level of complexity and design that meant that the cost and time scale to design, it was just too long.

However, the competition (from the latest generation of RISC architectures, for example) were already generating better performance. According to Wikipedia:

Long delays in the T9000's development meant that the faster load/store designs were already outperforming it by the time it was to be released. It consistently failed to reach its performance goal of beating the T800 by a factor of ten. When the project was finally cancelled it was still achieving only about 36 MIPS at 50 MHz.

The T9000 never reached production and its cancellation meant the end of Transputer development.

Some derivative designs such as the ST20, which was used in some embedded applications, were developed, but even these were eventually abandoned.

In 1994 STMicroelectronics ended use of the Inmos name. The company had finally come to the end of its short but turbulent history.

Lessons from Inmos

In Inmos and the Transputer - Part 1 we saw on how ambitious the Inmos plan had been. Manufacturing leading edge Static and Dynamic RAM, a radically new kind of microprocessor and associated software, with fabs on both sides of the Atlantic. All for $500m in 2023 dollars. A bargain!

I think it’s hard not to be impressed by what the INMOS team achieved.

Setting up a brand-new semiconductor company to make memories in competitive markets would have been a challenge. To do so on both sides of the Atlantic at the same time is very impressive. To add a new and highly innovate microprocessor architecture even more so.

But not only did Inmos end up being absorbed by a competitor but the Transputer disappeared entirely. Today it’s a footnote in computing history.

Many of the issues that INMOS faced still resonate today. The strategic importance of semiconductors as an industry. The extent to which state support is needed to protect and grow that industry. And the politics around that support.

So why didn’t Inmos and the Transputer succeed, and could their fate have been avoided? What did the founders of Inmos have to say about its fate?

The rest of this edition is for paid subscribers. If you value The Chip Letter, then please consider becoming a paid subscriber. You’ll get additional weekly content, learn more and help keep this newsletter going!