If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there

Lewis Carroll

Intel in its early years, following its founding in 1968, was a remarkable company. It used its leading-edge capabilities in semiconductor manufacturing to create and often lead a series of fast-growing new markets: first DRAMS, then microcontrollers, EPROMS, and of course, microprocessors and more.

New products were sometimes commercial or technical failures. We’ve discussed the iAPX432 ‘micromainframe’ chipset that made little or no impact as it was quickly withdrawn.

But the successful products were so successful that this didn’t matter. Intel grew rapidly and prospered.

Intel’s First Transformation

However, by the mid-1980s, Intel was starting to struggle, and Andy Grove and Gordon Moore made the difficult decision to exit DRAMs in 1985. Intel’s website records the announcement to staff on October 10.

Farewell to DRAM

Intel announced its withdrawal from the market for dynamic random access memory (DRAM). The decision wasn't easy – DRAM, introduced in 1970, was one of the company's first major innovations – but it proved to be wise. As Andy Grove explained, "It was an emotional decision. We had been the first to introduce the product and build the business ... In retrospect, getting out of DRAMs when we did was the best business decision we ever made."

The decision to exit DRAM made sense because Intel had a blockbuster product ready and waiting to go. A week later, on October 17, it announced the 80386 microprocessor.

Raising the Bar with the 386

Intel added the 80386 ("386") to its growing family of processors. With 275,000 transistors and a 16-megahertz clock speed, the 386 offered more than double the performance of the 286.

The 386 was created with, what was for the time, a huge investment in a single product.

Intel had spent $100 million developing the 386 and its support systems and built up massive expectations among its customers.

That $100m may not seem much today, but it represented almost 10% of the firm’s annual turnover in 1983 when the 386 project started.

And the bet soon paid off.

All the fanfare proved justified: In 1991, 386 sales alone accounted for about half of all Intel’s annual revenue.

The exit from DRAMs and the success of the 386 changed Intel. It became a 386 - or as we would say today an x86 - company. It had to change and it did, executing a major shift in strategy. One that led to explosive growth and market leadership for almost three decades. The change increased Intel’s focus, led to a concentration on profitable higher growth markets, and created the x86 moat.

Looking back at the execution of this change one thing is clear. Grove and Moore knew where they were taking the company and communicated that internally and externally through consistent messages and actions.

Intel’s Second Transformation

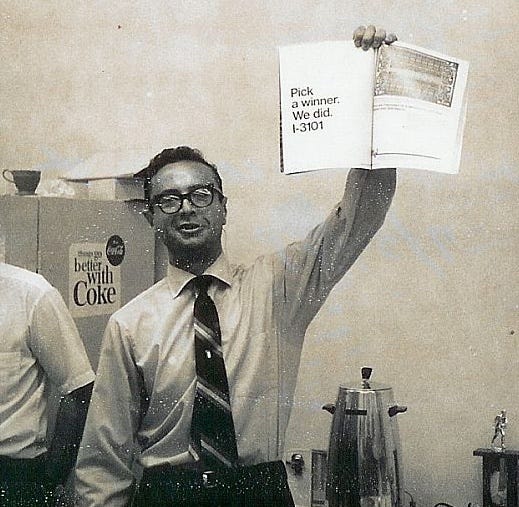

Intel’s current CEO Pat Gelsinger was closely involved in the development of the 386. So closely in fact that he had his initials etched into the 386’s die:

And Gelsinger spent many years working with Grove, a relationship that he acknowledges was often difficult:

“Mentoring with Andy Grove was like going to the dentist and not getting Novocaine. He was tough. He was hard, but he made me better"

Today Intel again needs another transformation. Gelsinger uses the word in the title of his recent message to employees:

A message from Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger to employees regarding the next phase of Intel's transformation

Reading this blog post and comparing it with Grove and Moore’s actions in 1985 two questions nagged away at me: does Gelsinger know where he is taking Intel and is he communicating this with consistent messages and actions?

Let’s take two excerpts from the memo. The first extols the benefits of IDM 2.0, the strategy of keeping Intel’s foundry together with its x86 product business:

This framework reflects the power of our “better together” strategy, anchored on our integrated portfolio across foundry services, infrastructure and x86 products.

Note the use of the word ‘integrated’.

This is followed in a section labeled ‘Greater Independence for Foundry’:

To build on our progress, we plan to establish Intel Foundry as an independent subsidiary inside of Intel. This governance structure will complete the process we initiated earlier this year when we separated the P&L and financial reporting for Intel Foundry and Intel Products.

A subsidiary structure will unlock important benefits. It provides our external foundry customers and suppliers with clearer separation and independence from the rest of Intel. Importantly, it also gives us future flexibility to evaluate independent sources of funding and optimize the capital structure of each business to maximize growth and shareholder value creation.

Note the phrase ‘clearer separation and independence’.

What is it to be, independent or integrated?

The messages here convey a Janus-like stance of looking both ways on the most important decision about Intel’s future, whether to retain or spin off Intel’s Fabs.

You might say it’s to be neither, that the destination is a balance between the two. But Intel is not standing still and the actions and messages point towards further change.

Maybe Gelsinger has a clear destination for the company. But if he does he isn’t communicating it. The contrast with 1985 couldn't be more stark.

And without a destination how can the company, its management, and its staff, be motivated to support its transformation?

We have recently had speculation about Qualcomm taking over Intel. The utter lack of sense in this notion is entertainingly dissected here by Irrational Analysis. This speculation is possible only because Intel hasn’t articulated a credible destination against which it can be measured.

It may be that there isn’t a credible - or perhaps palatable - alternative for Gelsinger to articulate. Ben Thompson’s recent piece Intel Honesty comes to just such a conclusion:

To summarize, there is no market-based reason for Intel Foundry to exist; that’s not a market failure in a purely economic sense, but to the extent the U.S. national security apparatus sees it as a failure is the extent to which the U.S. is going to have to pay to make it happen. … The tech world has moved on from Intel; the only chance for U.S. leading edge manufacturing is to do the same.

Perhaps Ben is correct and Intel’s future is unpalatable.

But nature abhors a vacuum. Someone will eventually fill Intel’s vacuum.

I wrote more about Andy Grove and the 386 in a paid post in January 2023.

Chip Letter Links No. 13: Andy Grove and the 80386

Hi everyone and thanks for subscribing. This is one of a regular series of posts with links, images and articles of interest, inspired by Adam Tooze’s excellent Chartbook.