Readers may have noticed a famous and distinguished name in computer architecture in the news recently:

GlobalFoundries to Acquire MIPS to Accelerate AI and Compute Capabilities

July 8, 2025

GlobalFoundries (Nasdaq: GFS) (GF) today announced a definitive agreement to acquire MIPS, a leading supplier of AI and processor IP.

“MIPS brings a strong heritage of delivering efficient, scalable compute IP tailored for performance-critical applications, which strategically aligns with the evolving demands of AI platforms across diverse markets,” said Niels Anderskouv, president and chief operating officer at GlobalFoundries.

The MIPS here, though, is MIPS (the company), not MIPS (the CPU architecture). Because what MIPS (the company) doesn’t bring to GlobalFoundries is MIPS (the architecture), as MIPS (the company) abandoned MIPS (the architecture) back in 2021, switching instead to RISC-V as EE Journal reported:

What a long, strange trip it’s been. MIPS Technologies no longer designs MIPS processors. Instead, it’s joined the RISC-V camp, abandoning its eponymous architecture for one that has strong historical and technical ties. The move apparently heralds the end of the road for MIPS as a CPU family, and a further (slight) diminution in the variety of processors available. It’s the final arc of an architecture … The new MIPS is MIPS in name only.

MIPS (the architecture) hasn’t completely disappeared (more on that later) but it’s downward trajectory is now steep.

MIPS (the architecture) was once a leading RISC architecture that, over multiple decades, powered hundreds of important designs ranging from high performance graphics workstations to internet routers to satellites. Billions of MIPS powered devices were shipped over more than three decades.

With all this success, how did MIPS (the architecture) come to fail?

Let’s start our investigation by going back to close to the peak of MIPS ‘glory days’ and a famous Italian plumber and his quest to capture a yellow rabbit …

In Super Mario 64, Nintendo’s hugely influential and popular 1996 game, a crudely rendered yellow rabbit makes a hyperactive but fleeting appearance. Locked in Princess Peaches’s basement, the rabbit allows the game’s eponymous plumber to gain two ‘power stars’. It then disappears, never to be seen again in this game, or any of its numerous successors.

The name of the yellow rabbit: MIPS

MIPS (the rabbit) was one of the first characters created by Super Mario 64’s designers and was used extensively for testing in the game’s early development.

Super Mario 64’s MIPS (the rabbit) was so named because the console that the game was developed for was powered by a ‘MIPS CPU’, licensed to and manufactured by NEC. That ‘MIPS CPU’ both:

Ran the MIPS ‘Instruction Set Architecture’; and was …

Designed by MIPS Technologies Inc.

Both MIPS the architecture and MIPS the company had their origins in the early 1980s as, first one of the first Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) designs developed at Stanford University by John Hennessy, and then an equally pioneering fabless microprocessor designer founded by a team including Hennessy and other Stanford researchers.

Why were the architecture and company called MIPS? According to John Hennessy:

The team wanted to pick a name for the project that emphasized performance. About nine months earlier, the RISC project at UC Berkeley had started, so we needed a catchy acronym. “Million instructions per second” (MIPS) sounded right, given the project’s goals, but this metric was also known as the “meaningless indicator of processor speed.” So, we settled on “microprocessor without interlocked pipeline stages.”

“… without interlocked pipeline stages” being one of the distinctive features of MIPS processor designs.

Alongside David Patterson’s Berkeley RISC project, MIPS blazed the trail for the RISC concept in the early 1980s.

More on Berkeley RISC here:

Over the next decade MIPS designs became more sophisticated culminating with the R4000 series, announced in 1991, one of the first 64-bit microprocessor designs. By this point MIPS was owned by one of its leading customers, workstation maker Silicon Graphics Inc (SGI).

The R4000 was adopted in a number of innovative computer designs. However, to truly take on Intel’s x86 PC architecture it needed one thing … volume. One market that could provide that was the growing market for games consoles.

MIPS’s R3000 32-bit CPU was chosen for Sony’s PlayStation entry into the console market, first announced in 1991 and launched in 1995. The clear market leader in consoles, though, was Nintendo whose Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) had almost 50 million units worldwide.

So when it was announced that Nintendo’s next console would use a 64-bit MIPS CPU along with custom silicon designed by MIPS owner Silicon Graphics the expectations (and hype) for the new console were soon off the scale.

From the outset of the project, the goal has been to create the best video game platform ever imagined. The 64-bit processors from Silicon Graphics' subsidiary MIPS Technologies Inc. are at the heart of the system and promise to deliver the quality of the finest Hollywood special effects with the speed necessary for real-time game play.

Nintendo Power Magazine April 1995

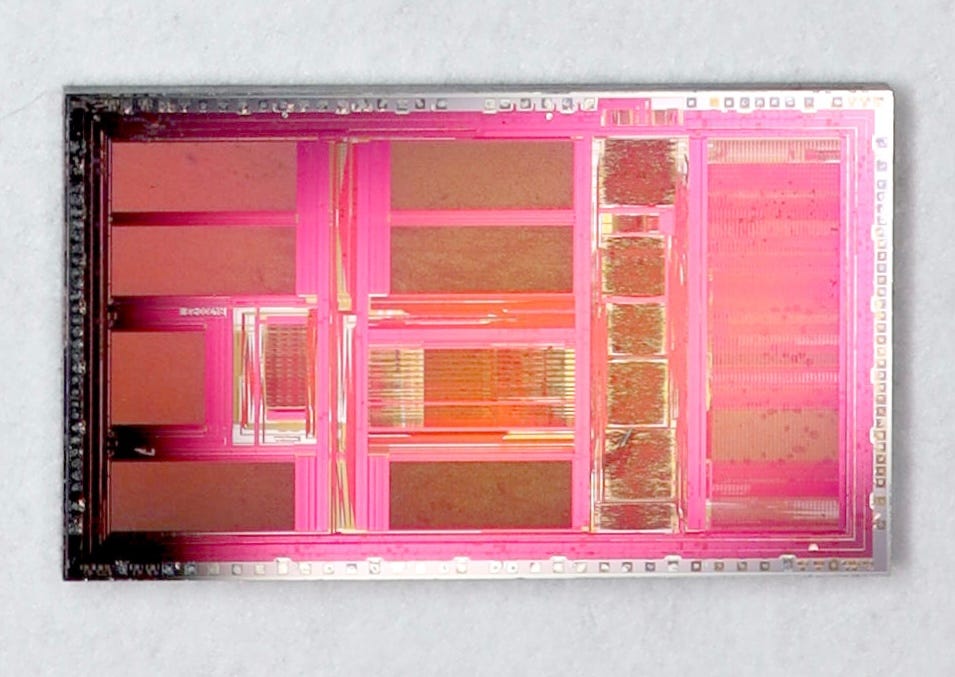

The CPU would version of NEC’s VR4300 itself a licensed version of the MIPS R4300i which in turn was a lower cost and low power derivative of the MIPS R4200, intended for use in embedded applications.

The ‘64-bit’ nature of the VR4300 was notable enough to give the console its name: the Nintendo 64.

Surely, with such an advanced MIPS design and Nintendo’s expertise in creating games, the Nintendo 64 would give both an insurmountable lead? It wasn’t to be.

The 64 bit MIPS CPU in the Nintendo 64 was, perhaps, a little overhyped: it was slowed down, for example, by using a 32-bit bus to transfer data to and from memory. Nintendo’s machine was also hindered by being late to market and by using ROM cartridges instead of CD-ROMs.

Sony’s PlayStation ended up outselling the Nintendo 64 by a factor of more than 3 to 1 (102m to 32m). Sony’s PlayStation 2 used another MIPS design and sold in very large volumes (160 units) but Nintendo (and ultimately Sony) abandoned MIPS in favour of IBM’s POWER architecture in their next generation GameCube. In that same console generation, Microsoft’s Xbox took advantage of Microsoft’s x86 software base and Intel’s volume and manufacturing prowess by using a version of the Intel Pentium III.

So, despite it’s success in a couple of generations of games consoles, MIPS never managed to defend its place as the CPU of choice for the latest designs.

MIPS (the company) was sold by a struggling Silicon Graphics in 1998. It would eventually be subject to a MIPS (the rabbit) like hyperactive series of corporate actions:

Acquired by Imagination Technologies in 2012;

Sold to Tailwood Venture Capital in 2017;

Sold to Wave Computing in 2018;

Wave Computing declares bankruptcy in 2020;

Wave Computing emerges from bankruptcy in 2021 as MIPS.

And here is the rub; an unstable corporate parent is the last thing an Instruction Set Architecture needs.

Along with changes of corporate control came a number of switches in strategy and what - perhaps with the benefit of hindsight - were clear missteps and failures.

The contrast with longtime RISC CPU rival ARM’s consistent focus, business model and stable corporate structure couldn’t be more stark. Culture Won, the book by former ARM VP Keith Clarke, has a section that sets out various contests between ARM and MIPS over the years, starting with the fact that MIPS (both the architecture and the company) had a multi-year head start over ARM:

.. the MIPS Computer Systems' R3000 was a RISC processor available to license as an embedded microcell two years before the foundation of Advanced RISC Machines.

The book concludes with a reflection on MIPS’s demise:

ARM took no pleasure in the demise of such a competent technical competitor. The MIPS processors had spurred ARM to develop many features and products to help its partners win new to sockets. The competition had been very good for ARM.

So MIPS is now effectively a footnote in technology history. But it’s an important footnote. Just a few highlights of the roles that MIPS architecture designs have played over its 40 year history:

Pioneering early (1984) fabless semiconductor design company;

Early in licensing embedded processor designs to manufacturing partners (R3000 in 1988 as noted, several years ahead of ARM);

Second architecture (before x86) used as a target for the development of Microsoft’s Windows NT;

Along the way MIPS powered some interesting machines, for example the SGI Tezro a graphics workstation from 2003, running IRIX and with up to four MIPS 16000 processors.

We mentioned that MIPS the architecture hadn’t completely disappeared. It lives on in (probably hundreds of millions of) devices still in use today. It’s supported in the Linux Kernel and you can still compile code for various MIPS architectures using popular compilers (here is some MIPS Asssembly output from Compiler Explorer);

Perhaps MIPS’s most significant legacy though is in China. The first Godson processor was designed in 2001 using a MIPS-like instruction set: simply omitting a small number of patent encumbered MIPS instructions. Loongson technology then licensed the full MIPS architecture in 2007 before moving to its own LoongArch architecture, widely seen as a fork of the MIPS architecture, in 2021.

So perhaps the most consequential part of the legacy of MIPS (the architecture) may be as one of the steps that China has used to build its technology capabilities.

The ultimate fate of MIPS (the company) though seems likely to be to provide a minor boost for GlobalFoundries never to be heard of again. A little like MIPS (the rabbit).

MIPS (the rabbit) may have a minor role in Super Mario 64 but it’s not been completely forgotten for example in this fun YouTube documentary - which also provided the Mario / MIPS images used above.

I love the Chip Letter, but confess to a sizable backlog. Nevertheless, I read the recent MIPS post immediately. How could I not? I joined MIPS as VP of Engineering in 2004 not long after the company exited their custom and semi-custom 64-bit CPU business and refocused on 32-bit processor IP.

The problem had been that games and printers are classic “razor blade business models” - making money, on game or ink cartridges, almost regardless of the CPU cost. During MIPS extended focus on 64-bit, well after its spin out from SGI, the upstart Arm moved steadily along their 32-bit roadmap, until they dominated the far broader embedded market and, crucially, won the smartphone (which created a wide moat after the 3rd party app store developed).

When we (MIPS) refocused on 32-bit IP we could beat, sometimes easily beat, Arm’s performance metrics but by then that wasn’t enough to dislodge Arm; the unit shipment and revenue gap grew inexorably. Today, I’m delighted to see MIPS’ outstanding RTL retargeted and reincarnated as RISC-V. As many of you know, the base RISC-V ISA is MIPS-I with minor tweaks, however, the vastly different RISC-V business model offers real opportunity at MIPS’ new home, Globalfoundries.

The MIPS history deserves a full book. Meanwhile - shameless plug - you might enjoy the story of my time at MIPS: Section 5 of Silicon Planet (Amazon).

—Pat Hays