Modern Baby

A pioneering computer from Manchester

Finally, when we pressed the start button it set off on this usual dance of death and then suddenly it stopped and there in the expected line was the expected answer.

So we'd built a computing machine.

When and where was the first truly modern computer built and run? Would it surprise you if I said in 1948 in Manchester in the UK, a city better known for its role in the industrial revolution?

After John von Neumann’s paper First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC was circulated by Herman Goldstine, a number of copies made their way across the Atlantic and into the hands of some of the engineers who had worked on the development of the Colossus code-braking computer.

After developing the Colossus computer for code breaking at Bletchley Park during World War II, Max Newman was committed to the development of a computer incorporating both Alan Turing's mathematical concepts and the stored-program concept that had been described by John von Neumann. In 1945, he was appointed to the Fielden Chair of Pure Mathematics at Manchester University; he took his Colossus-project colleagues Jack Good and David Rees to Manchester with him, and there they recruited F. C. Williams to be the "circuit man" for a new computer project for which he had secured funding from the Royal Society.1

Williams then recruited his former colleague Tom Kilburn to help. Neither man had any familiarity with computers before starting on the project, with Williams later recalling:

Now let's be clear before we go any further that neither Tom Kilburn nor I knew the first thing about computers when we arrived at Manchester University ... Newman explained the whole business of how a computer works to us.

Together with a small team, including Geoff Tootill and David Edwards, the two men set out to build a computer according to von Neumann’s principles.

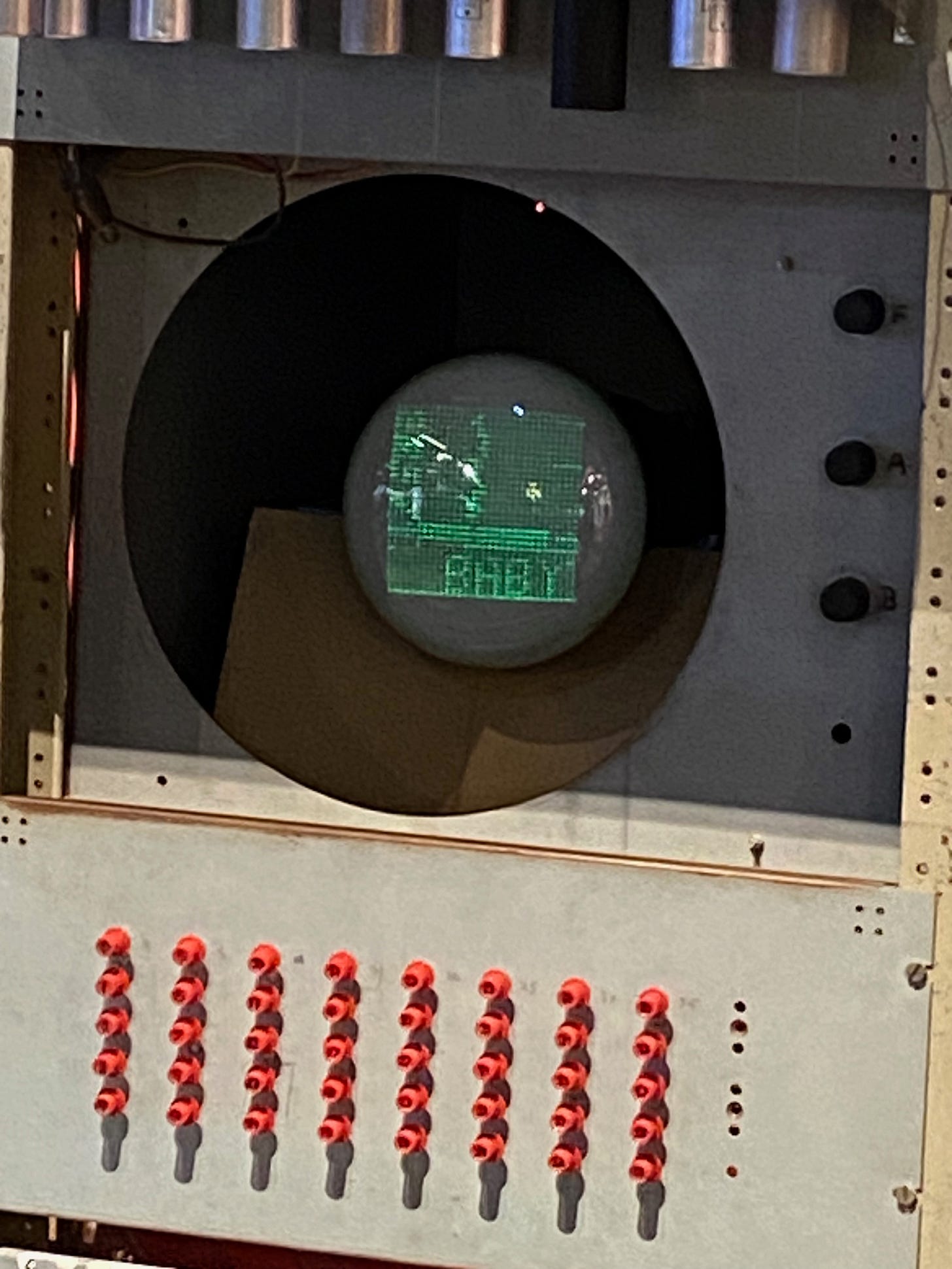

Central to the project was the Williams-Kilburn tube, a Cathode Ray Tube adapted to act as random access memory. In fact their first step was to build a machine as a ‘proof’ of concept that the Williams-Kilburn tube would work as a memory store.

The result was the ‘Small Scale Experimental Machine’ - better known now as the ‘Manchester Baby’.

Manchester Baby ran its first program on 21 June 1948:

It was designed to find the highest proper factor of 218 (262,144) by trying every integer from 218 − 1 downwards. The divisions were implemented by repeated subtractions of the divisor. The Baby took 3.5 million operations and 52 minutes to produce the answer (131,072). The program used eight words [32-bit] of working storage in addition to its 17 words of instructions, giving a program size of 25 words.

The ENIAC Debate

‘Baby’ is now usually awarded - including for example by Wikipedia - the title of first ‘electronic stored-program computer’. It’s a claim that is, however, disputed.

Back across the Atlantic the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) ran its first program in 1945. In its first configuration, ENIAC had to be reprogrammed by rewiring some of its circuitry. This first version of ENIAC was electronic but definitely wasn’t a stored-program computer.

ENIAC was later remodelled to adopt the principles set out in von Neumann’s ‘First Draft’ paper. These changes were originally thought to have been implemented in September 1948. However, later research established that this adaptation took place a few months earlier and that the first program using the revised design was first run before Manchester Baby was operational.

The article Programming the ENIAC: an example of why computer history is hard from the Computer History Museum sets out the story of this revision to the history:

A recent book by computer historian Tom Haigh and colleagues Mark Priestley and Crispin Rope explores the conversion of ENIAC into what they prefer to call a “modern code paradigm” computer. Based on machine logs and handwritten notes, they have discovered that a complex program began running on ENIAC on April 12, 1948.

The ENIAC’s program was held in an array of rotary dials, known as ‘function tables’.

The proponents of ENIAC as the first ‘electronic stored program computer’ say that these rotary dials are equivalent to modern-day ‘Read Only Memory’. Quoting from the CHM article:

Was the modified ENIAC less of a computer than the Manchester Baby because its program was in ROM and could not be changed by the computer? …

Look at it this way: many modern microprocessors, especially small ones for embedded control, have their programs in ROM. If they are modern-style computers, then so was the modified ENIAC. That’s my opinion, anyway; you are free to add or subtract your own adjectives and reach a different conclusion.

No-one would claim that a modern Harvard Architecture computer with its program stored in ROM isn’t a stored-program computer. So does ENIAC take the prize from Baby as the first electronic stored-program computer?

ENIAC book author Crispin Rope makes the case for a division of the prize between the two machines.

It seems reasonable to argue that the Manchester Baby's achievement is wrongly singled out as the clear first in the stored-program stakes. Equally it would be wrong for ENIAC to steal that whole prize.

Baby, ENIAC or shared? This is where it gets difficult but there are several points that still favour the Baby’s claims.

One is that those mechanical rotary dials in the ENIAC aren’t electronic. To my mind at least they hover somewhere between a non-electronic form of ROM and a mechanical rewiring of the computers circuits.

So perhaps we could say that the Baby was the first ‘fully electronic’ stored program computer and the second version of the ENIAC was a hybrid electronic-mechanical stored-program computer.

But there is another way in which the way in the program storage used by the two machines matters in this debate. In the ENIAC the form of the storage (decimal) was quite different to that of the data that ENIAC operated on (binary). I think this creates a strong dividing line between ENIAC and all the computers that followed. Even with the now-antiquated nature of its circuitry - valves, cathode ray tubes and so on - Baby, with its all-electronic circuitry and program encoded in binary, is clearly on the modern side of that line.

In fact, it’s remarkable just how modern the architecture of the Baby looks even today. Let’s examine some of the elements.

Registers

Baby had a single 32-bit accumulator and a 5-bit program counter.

Memory

Baby used a true ‘von Neumann’ architecture with thirty-two 32-bit words used to store both program and data.

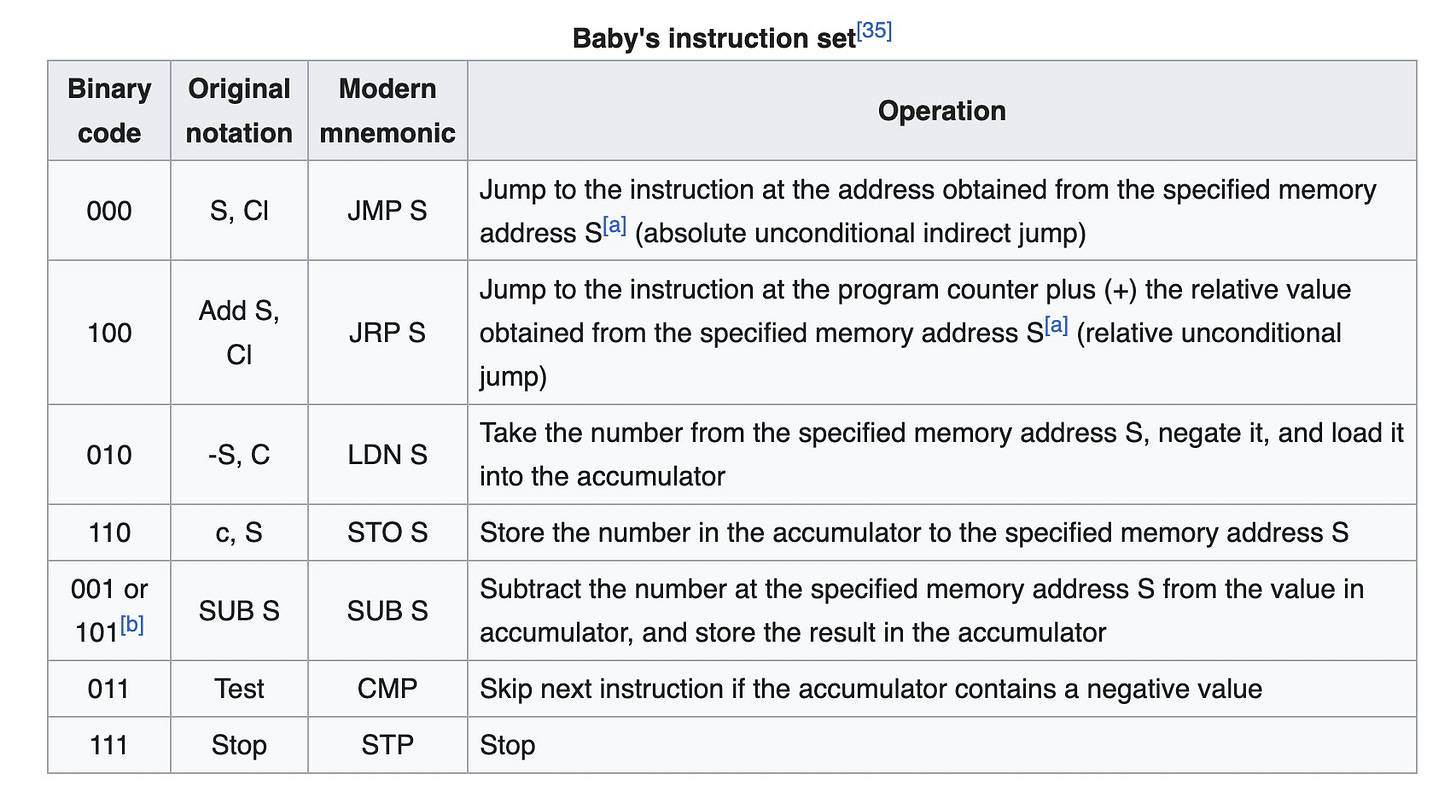

Instruction Set

Baby had a simple set of instructions with just eight distinct operations.

These opcodes formed part of a 32-bit instruction word that also included a 5-bit memory address (so that most of each instruction 32-bit word was ignored).

There were all the key types of instruction seen in a modern instruction set.

Load and Stores

LDN S

STO S

Control flow

JMP S

JRP S

STP

Arithmetic

SUB S

Logic

LDN S

Conditional Jumps

CMP

Note that there was no ADD instruction as addition could be achieved using a LDN S instruction combined with SUB S.

Readers who want to explore what Baby was capable of can try the terrific JsSSEM online emulator.

A short screen capture of the emulator in action is embedded below.

By way of contrast to Baby’s modernity here is a short extract from A logical coding system applied to the ENIAC the key document describing how the modified ENIAC was programmed.

Cathode Ray Tube Display

Finally, Baby’s use of a Cathode Ray Tube as a computer display is a feature that would last for more than another six decades.

In fact one might sat that Baby had the first ‘memory-mapped’ computer display and one which was capable of displaying moving images. The program shown running above has ‘BABY’ shifting across the screen from left to right.

Baby Grows Up

One of the criticisms levelled at Baby’s claims is that it was only a ‘toy’ computer that was never used for real work compared to the more ‘serious’ ENIAC. The CHM article is a little dismissive:

It took 52 minutes to give an answer we already knew, on a machine that never did any useful computations of new results and was soon taken apart.

In fact the baby was only ever intended to be a prototype. It was soon expanded and then dismantled.

The Baby was then expanded over the next 18 months to create the Manchester University Mark 1 computer. It was made about three times bigger, it had a lot more store and so on. By then, as far as the engineers were concerned, the Baby computer was old hat. There's nothing left at all of the Baby or the expanded Baby.

F.D. Williams, who had led the project, had little interest in continuing work on computers. He would later say:

I'm not really interested in computers, I made one and I thought one out of one was a good score so I didn't make any more.

Baby’s Significance

I don’t hold too much store in ‘firsts’. They are usually nuanced, often disputed, and any invention almost certainly makes extensive use of the work of others. That’s certainly true in the case of Baby. The project only came about because the team had access to John von Neumann’s ‘First Draft’ paper.

But there is a big gap between having access to a paper that describes the theory and having a working computer. John von Neumann’s paper was definitely not a manual for how to build a modern electronic computer.

Almost eighty years on it’s striking how close the Baby is to our modern conception of a computer. The small, inexperienced team at Manchester did a remarkable job. They boiled down the ‘von Neumann’ concept to its essentials and, as any sensible engineer would do, built ‘a proof of concept’ machine to prove that their technology worked. They certainly deserve their place in history.

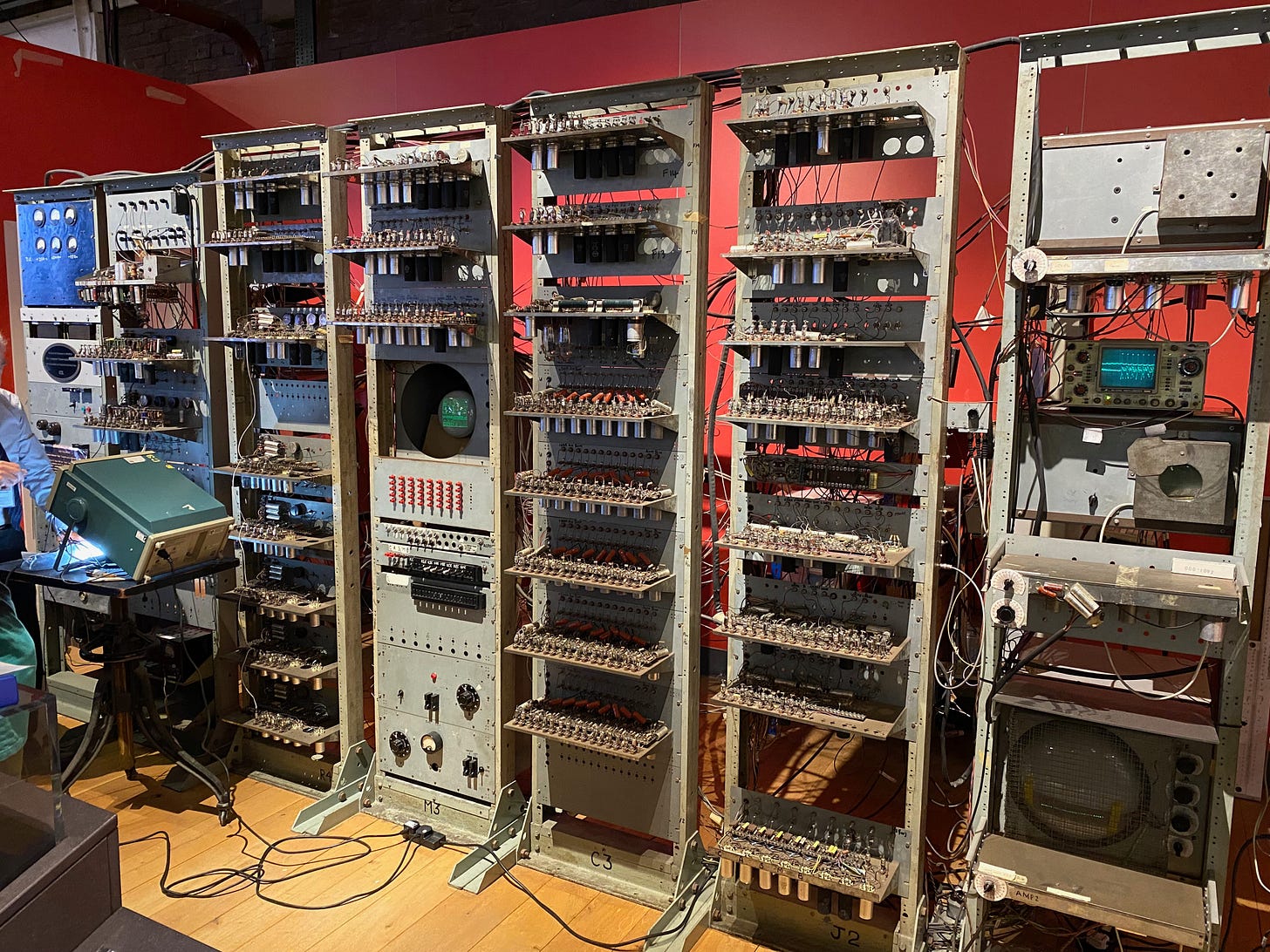

Replica Baby

In 1994 a project was initiated to create a replica, under the supervision of some of the original team including Tom Kilburn and Geoff Tootill. It’s this machine, a fully working replica that sits in the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester today.

The location of the Manchester Baby replica may be a little off the beaten path for most readers, but if you can make it then it’s worth the trouble. When I visited recently the staff I spoke with were really helpful and highly knowledgeable.

In the meantime this short video, featuring several members of the original team who built the Baby, is terrific. I’ve added a transcript below.

Simon Lavington2: In about 1966 I asked Professor Kilburn, why is it whenever I open a computer science textbook I get the American origins of computers but the Brits are nowhere?

So Tom took his pipe out of his mouth and said those who need to know do know.

What was special about the Baby was that such a computer can be used for a wide variety, perhaps almost an infinite variety of problems. It was an engineering testbed to test out the reliability of a memory invention.

(voice of) F.C Williams: The central problem of the computer was recognised to be the problem of storage and so the problem was quite simply brought to my notice

Chris Burton3: Cathode ray tubes were used widely during the second world war for radar purposes.It's a way of displaying electronic signals on a screen that you can see.

Simon Lavington: In a Williams and Kilburn storage tube each little element of the screen was excited by the electrons and became charged and each area of stored charge was made to represent a binary digit, a 1 or a 0.

David ‘Dai’ Edwards4: F.C. was a member of the telecommunication research establishment which was called TRE.

Geoff Tootill: At the end of the war he was offered a post at Manchester university and he accepted with enthusiasm and he took one of his chaps, Tom Kilburn and also asked for other bright young men, so I was the next one.

(voice of) Tom Kilburn: It was a very exciting time, there were a very small number of people who worked together very closely indeed.

David Edwards: Tom Kilburn worked on the CRT memory and in about a year he'd actually moved from one bit of storage to one thousand to two thousand bits of storage.

In December '47 what had arrived was a memory which could show static pictures.

Now what we needed to check was that those pictures could actually change, be recorded properly, and do that at electronic speeds. That's really why the Baby was built.

Geoff Tootill: It consisted of 6 ft 6" high post office racks, 23 inches wide all round the laboratory.

David Edwards: It was just a simple room. It had no air conditioning so we always had windows open and things in those days, you know, to keep the temperature sensible.

Geoff Tootill: This was the centre of Manchester and in with the fresh air came the dirt. Tom and I wore lab coats a long coat down to your mid-thighs or knees.

We avoided electric shocks by the classic artifice of keeping one hand in your pocket all the time and never to touch anything with both hands at once

David Edwards: We had a couple of technical staff who did did the actual building.

Geoff Tootill: One of the best wiremen we had was Ida Fitzgerald I think was her surname.

She delivered the chassis wired to our diagram and we would look at it and say oh dear, I didn't mean to do that and we would proceed to alter Ida's neat wiring.

Simon Lavington: Tom Kilburn and Geoff Tootill had been struggling for some days.

The machine kept failing, perhaps it was a wiring error or some soldered joint had failed and then one day it all held together and worked not just once but twice but three times and they realised we've made it.

(voice of) Tom Kilburn: Finally when we pressed the start button it set off on this usual dance of death and then suddenly it stopped and there in the expected line was the expected answer so we'd built a computing machine

Geoff Tootill: We went out to lunch in the canteen as usual, and we were actually having lunch instead of having brought in sandwiches, that was the way we celebrated.

David Edwards: What was needed now was to develop both the programming side and the arithmetic side to develop this universal machine.

Chris Burton: The Baby was then expanded over the next 18 months to create the Manchester University Mark 1 computer. It was made about three times bigger, it had a lot more store and so on.

By then, as far as the engineers were concerned, the Baby computer was old hat.

David Edwards: There's nothing left at all of the Baby or the expanded Baby.

In fact the racks that the Baby and the expanded Baby were built on were used for the next machine that we built

Chris Lavington: In 1994 I realised that in four years time it would be the 50th anniversary of the Baby computer. I put together a proposal as to how we could build a replica of that original machine.

Geoff Tootill: Tom Kilburn and I both vetted it and approved it and as we said to each other when we saw it, oh this is all wrong of course, it's nice and clean.

Chris Burton: We completed the replica build and re-enacted the running of the world's first program.

They operated the switches, the program ran, they stood back, watched it on the display tube, saw the answer was correct and then turned away and grinned at the audience, as if to say there we can do it again.

Simon Lavington: Normally the people who did the original work tend to fade into obscurity.

In England it's scientists and theoreticians who tend to get the glory

It's good that we remember the contribution of the electronic engineers to the information age, to the second industrial revolution if you like

Geoff Tootill: Manchester University now has a Tom Kilburn building which in fact contains two laboratories known as the Tootill laboratories

Chris Lavington: Computers are everywhere today in places unimaginable to the pioneers

David Edwards: The Baby started off with a thousand bits of storage and now there's so much storage everywhere, you know a million million million amount of storage, that in my terms is science fiction

Interviewer: How do you foresee the development of computers over the next decade?

(voice of) F.C Williams: I'm not really interested in computers, I made one and I thought one out of one was a good score so I didn't make any more.

Programming the Baby

If you want to explore programming the Baby in more depth here is a thorough programming tutorial including the obligatory ‘Hello World’.

Wikipedia Manchester Baby

Manchester University Research Student (1962-5)

Project Leader - Baby Replica

Manchester Baby Research Student (1948-9)

once again, this article is neglecting the role of Konrad Zuse:

Konrad Ernst Otto Zuse (/ˈzuːsə/;[5]German: [ˈkɔnʁaːt ˈtsuːzə]; 22 June 1910 – 18 December 1995) was a German civil engineer, pioneering computer scientist, inventor and businessman. His greatest achievement was the world's first programmable computer; the functional program-controlled Turing-complete Z3 became operational in May 1941. Thanks to this machine and its predecessors, Zuse is regarded by some as the inventor and father of the modern computer.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

more can be read on Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Konrad_Zuse

—Henry

You say, "In the ENIAC the form of the that storage (decimal) was quite different to that of the data that ENIAC operated on (binary)." Actually, ENIAC's 20 10-digit accumulators were decimal. Source: Wikipedia, and various references it cites:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ENIAC