Innovation, Customers and Scale: A Positive Vision for Intel's (Foundry) Future

But more change is needed if this vision is to be realised

I’m not sure whether it’s great or appalling timing but this post was ready to send out when this happens!

It’s a bit too early, I think, to make sense of what this means and in the meantime, I don’t think it changes my views on anything material in what follows. So here is the original post written in the context of the Gelsinger-era Intel.

I’ve written some pessimistic and critical posts on Intel recently. And I’m not alone!

It’s time for something much more positive!

Disclaimer: This post puts forward a possible future for Intel’s Foundry business and not for Intel’s Corporation as a whole or for Intel’s stock price. This is not investment advice. See further comments at the end of the post.

Fairchild and Intel’s Early Years

In the late 1950s and early 1960s military contracts were key in supporting Fairchild Semiconductor's early success:

The speed with which the group had designed the transistors while solving process and manufacturing problems gave Fairchild Semiconductor a monopoly on diffused silicon transistors for nearly a year. In this, Fairchild Semiconductor mounted the greatest challenge to Texas Instruments' silicon transistor business that TI had yet faced. Fairchild Semiconductor's NPN mesa transistor had significantly better electrical characteristics than TI's devices made by grown-junction and diffusion techniques.

In particular, it could handle more power than TI's transistors. This characteristic made it attractive for engineers designing a variety of electronic circuits, ranging from logic circuits to circuits that required power transistors. As a result, Fairchild's device was a "universal transistor" of sorts—a transistor that could be used in many different military applications.

The diffused silicon mesa transistor attracted considerable attention in the electronics industry and generated a large number of inquiries. In the late summer and fall of 1958 and early in 1959, Fairchild Semiconductor's sales department received hundreds of orders. These orders, mostly for small quantities, came from engineering groups at military contractors that were interested in evaluating the device for possible use in systems they were designing. Some orders were for devices that would control the hydraulics of airplanes and missiles. A large number of orders came from firms that developed avionics systems, including digital computers, for military aircraft and mis-siles. This was a fast-growing market, as the United States' ballistic missile programs continued to expand through 1958 and 1959.

From Makers of the Microchip: A Documentary History of Fairchild Semiconductor

The importance of military contracts to the early development of Silicon Valley is well known. What may be a surprise is the scale at which Fairchild Semiconductor was operating in its early years; it was tiny. Quoting from the Fairchild Camera & Instrument Annual Report 1958 (my emphasis):

Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation

This corporation, Fairchild's stake in the extraordinarily fast-growing market for transistors, advanced from the research and development stage to successful production and substantial sales during 1958. Employees increased from 20 at the beginning of the year to 165 at the end, and are expected to triple or more during 1959 …

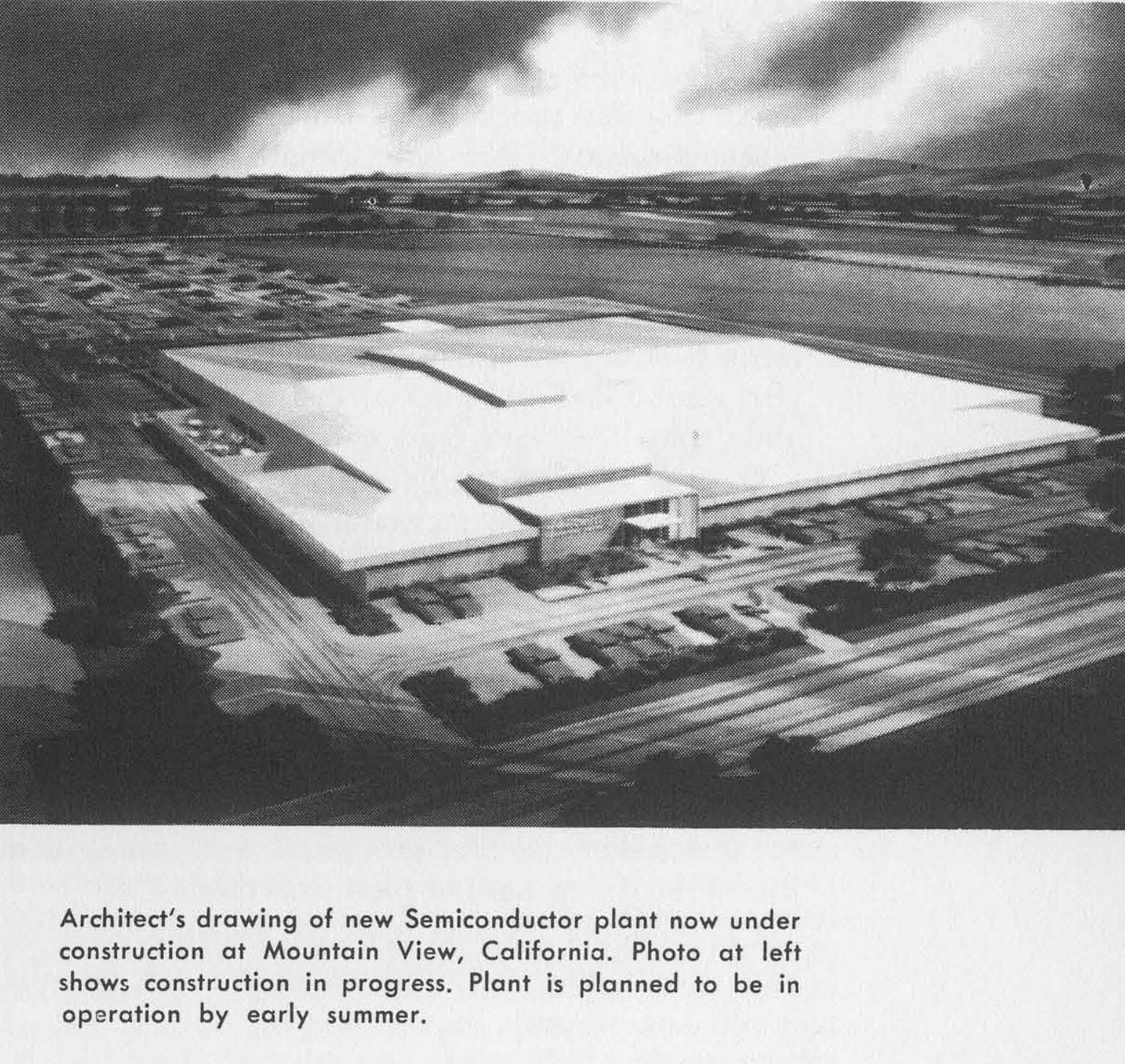

Ground was broken during the year on a new 64,000 square foot manufacturing plant which is scheduled for occupancy by mid-1959. At that time, the present 20,000 square foot plant at Palo Alto California, will be devoted to an expanded research and development program.

Fairchild Semiconductor was, at that time, much closer to the modern definition of a Foundry. The circuits it made were simple and most value added by Fairchild was in the fabrication of those circuits rather than in any design expertise.

It may have started small but Fairchild Semiconductor would have a huge impact, neatly summarized by TechCrunch in The First Trillion Dollar Startup:

The story of Fairchild illustrates how entrepreneurs can reshape their local communities. When successful founders generate new spin-off companies, mentor others and act as early-stage investors it increases the opportunities available to new generations of entrepreneurs. The intellectual, social, and financial capital that successful founders reinvest into new companies strengthens the local entrepreneurship community and enables successful hubs, like the original Silicon Valley, to develop.

… the full value of the company can only be measured by tracing the way the firm’s success has been reinvested into new founders and companies. By this measure, Fairchild is the Valley’s first trillion-dollar startup. It might even be the most important entrepreneurial company of the last hundred years.

Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore were among the 20 employees of Fairchild Semiconductor in 1958.

A decade later, in July 1968, they founded Intel. Many of Fairchild’s most talented engineers, including Andy Grove and Federico Faggin, joined them at the new company. Intel was a startup though and was sufficiently small that the whole company could fit in a single combined office and fab in Mountain View.

They even posed for a photo outside.

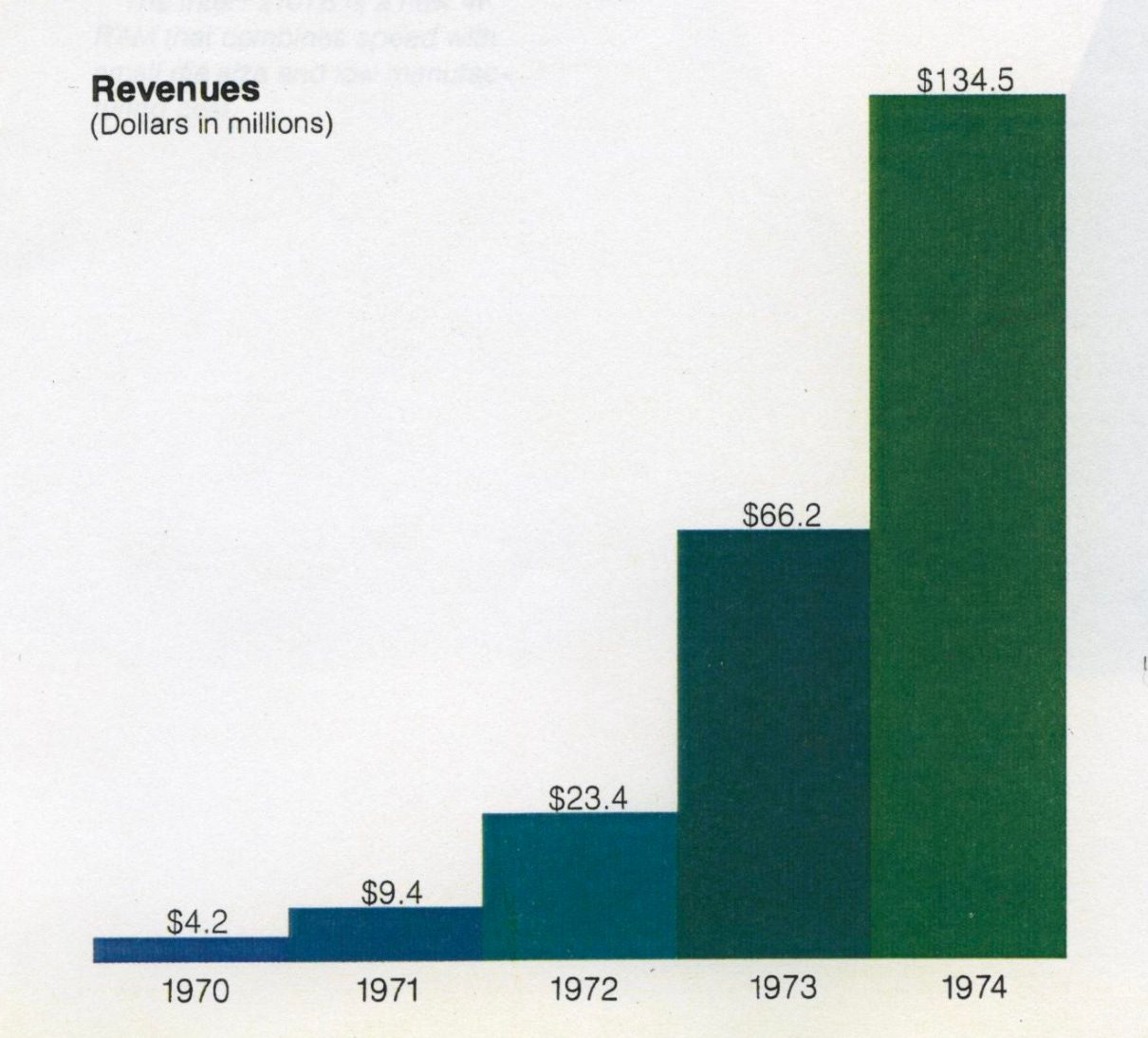

From this modest start, Intel grew rapidly, again whilst competing against much bigger, firmly established competition.

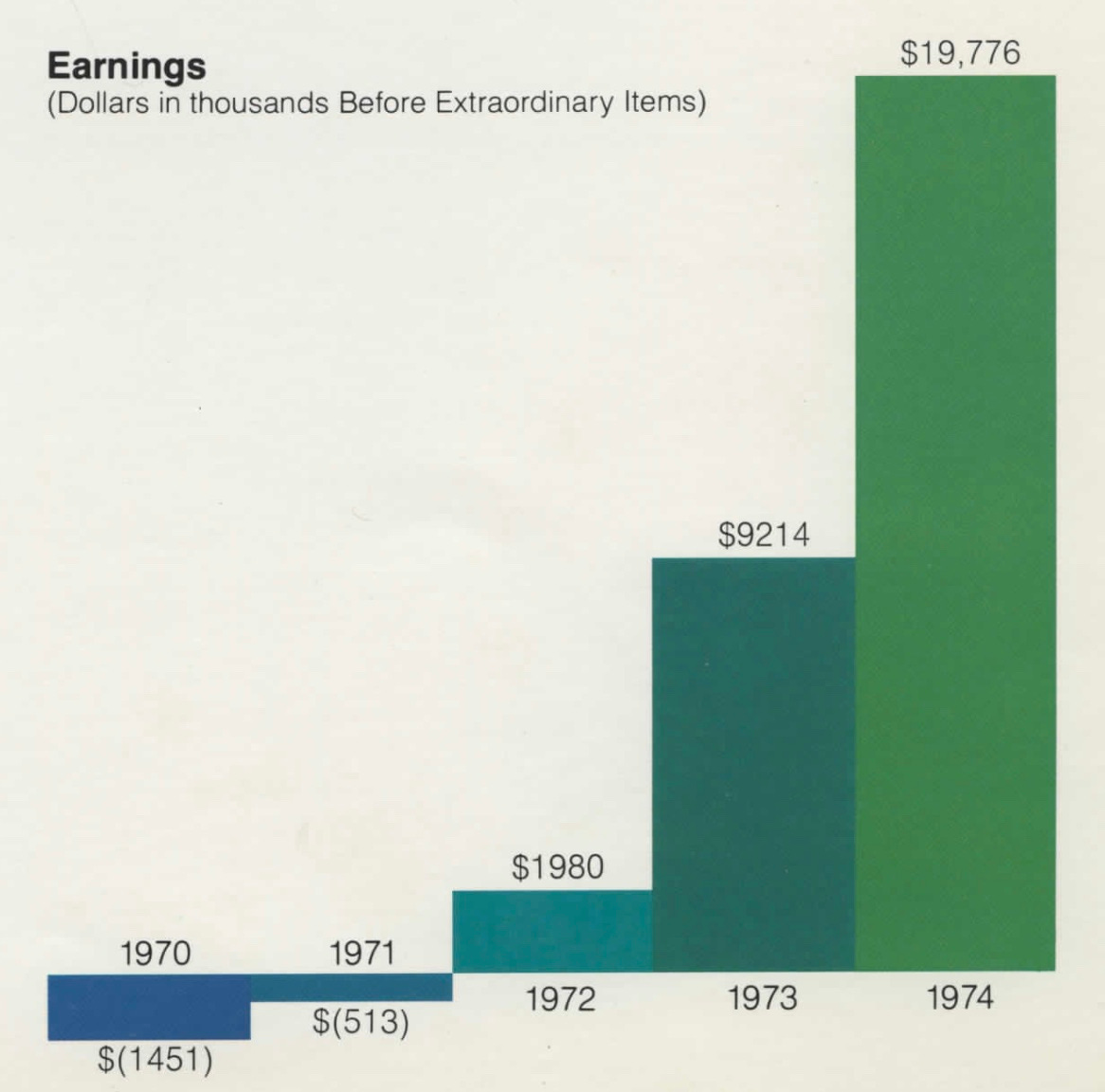

and it was soon profitable:

Why was early Intel so successful in those early years? Staffed by talented engineers, many of whom had moved from Fairchild, the company was highly innovative.

Early innovations included:

the first commercial MOS field-effect transistor (MOSFET) silicon gate SRAM chip;

the first commercially available dynamic random-access memory (DRAM));

the first commercial microprocessor;

the first Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory.

Crucially, these innovations were turned into successful commercial products.

the first commercial MOS field-effect transistor (MOSFET) silicon gate SRAM chip, the 256-bit 1101 (1969);

the first commercially available dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), the 1103 (1970);

the first commercial microprocessor, the 4004 (1971);

the first Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory, the 1702 (1971).

The original plan was to focus on DRAMs but the product portfolio was soon much broader and came to embrace microprocessors, microcontrollers, and a lot more besides.

Indeed in DRAMs, at the start of the 1980s, famously Intel would stumble and be forced to leave the market it founded - unable to compete on price and quality with Japanese firms - only to be saved by its microprocessor business.

For a summary of Intel’s story over this period, the recent video from

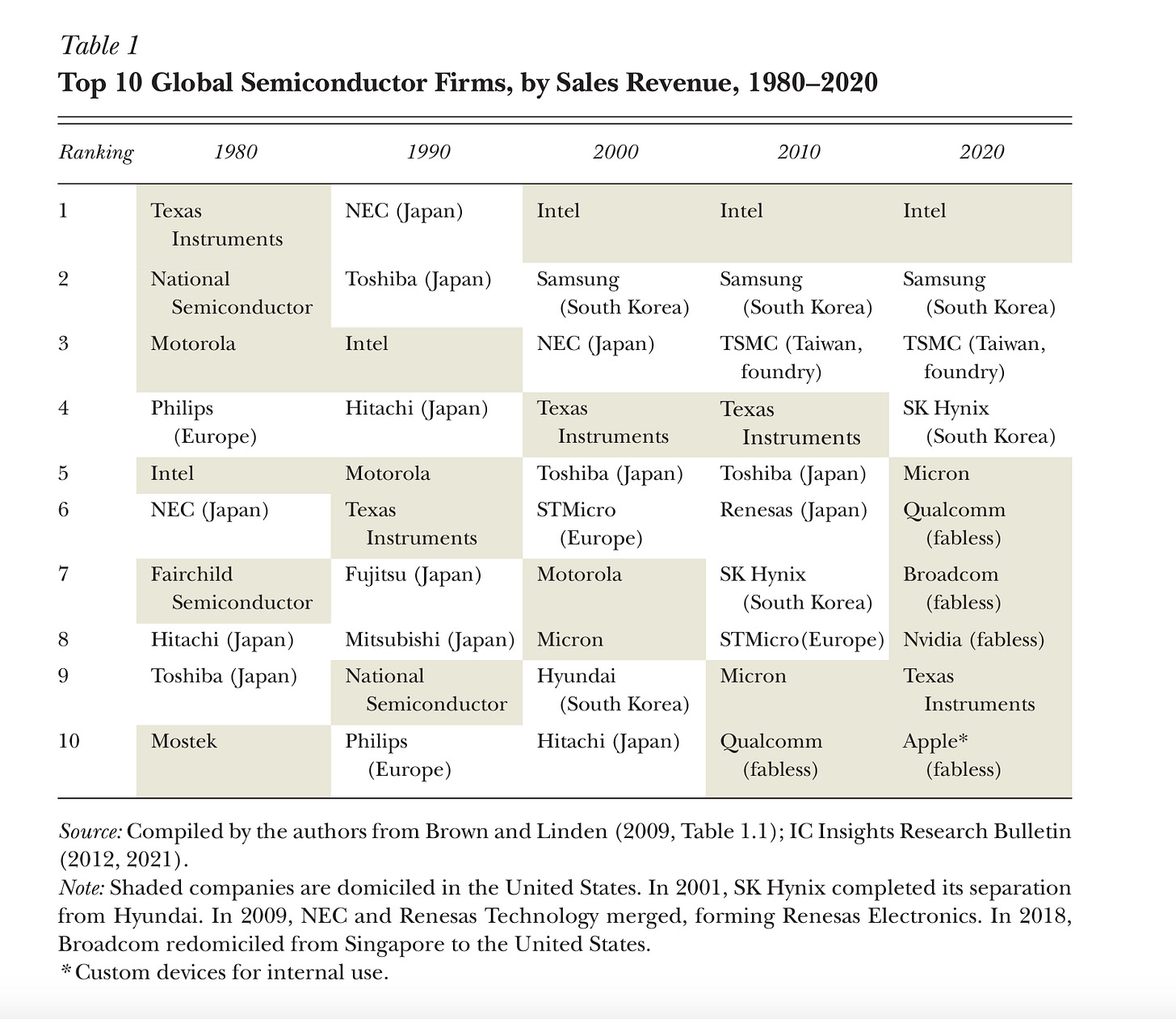

is terrific.As we know, Intel would ‘retreat’ behind its x86 microprocessor moat. The x86 series was so successful that it enabled Intel to climb the ladder of the world’s largest semiconductor firms from a humble Number 5 in 1980 to Number 1 by the end of the 1990s, a spot it held until the start of the 2020s.

Moore and Scale

As Intel and the semiconductor industry developed Gordon Moore predicted how both its products would progress - in the shape of ‘Moore’s Law’ - and also how the industry would grow. We looked at this in more detail in Moore on Moore:

Moore on Moore

The definition of "Moore's Law" has come to refer to almost anything related to the semiconductor industry that when plotted on semi-log paper approximates a straight line.

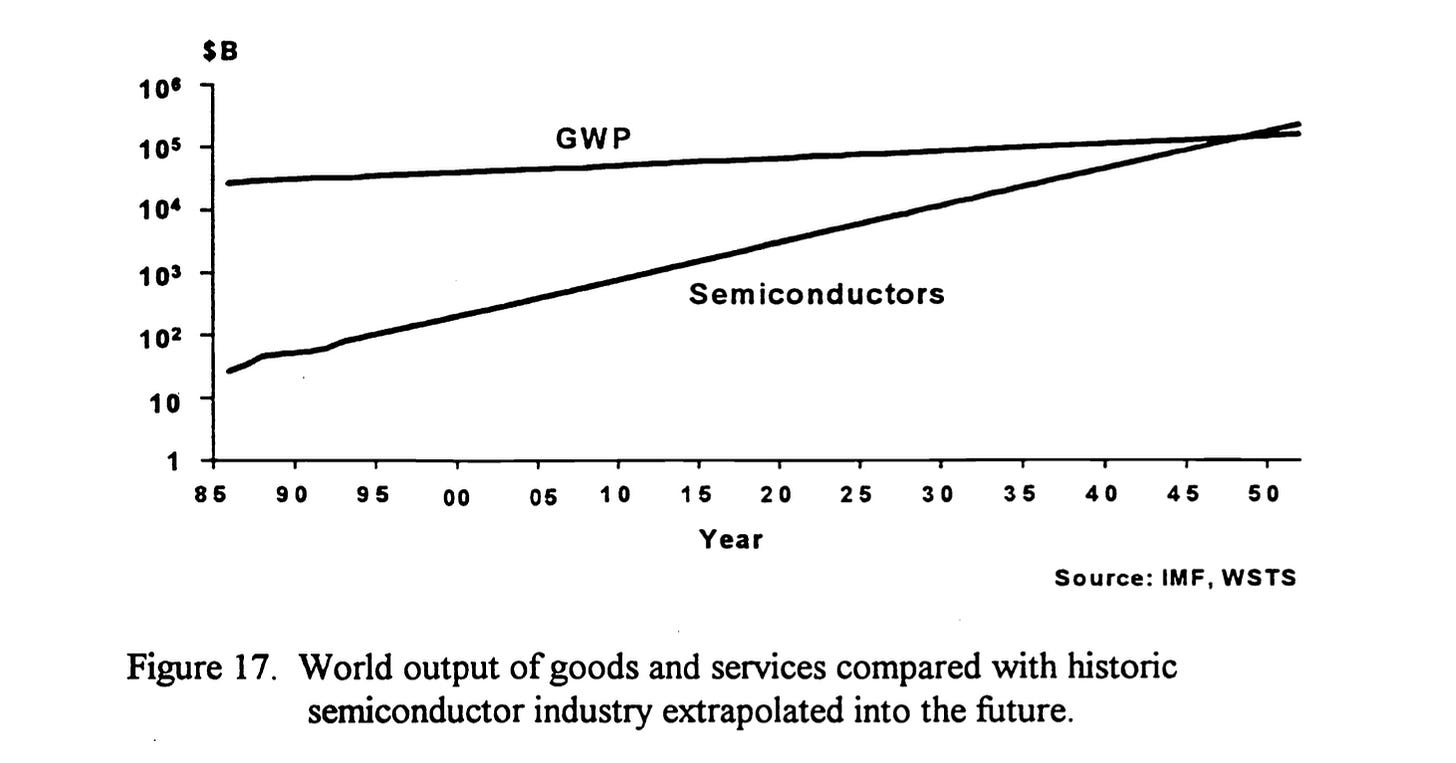

Moore predicted huge growth in the scale of semiconductor manufacturing:

Quoting from that earlier post:

Moore commented on this chart:

As you can see, in 1986 the semiconductor industry represented about 0.1 percent of the GWP. Only ten years from now, by about 2005, if we stay on the same growth trend, we will be 1%; and by about 2025, 10%. We will be everything by the middle of the century. Clearly industry growth has to roll off.

I do not know how much of the GWP we can be, but much over one percent would certainly surprise me. I think that the information industry is clearly going to be the biggest industry in the world over this time period, but the large industries of the past, such as automobiles, did not approach anything like a percent of the GWP. Our industry growth has to moderate relatively soon. We have an inherent conflict here. Costs are rising exponentially and revenues cannot grow at a commensurate rate for long. I think that this is at least as big a problem as the technological challenge of getting to tenth micron.

By my estimate the total revenue of chipmakers in 2023 around a quarter of one percent of global GDP, so Moore was off, in this case, by more than an order of magnitude. His fundamental point still stands though. This relationship must ultimately impose a constraint on how big the industry can grow.

Moore overshot somewhat in his prediction but still: a quarter of one percent of global GDP!

This growth has been accompanied by, as alluded to by Moore, costs that also rose exponentially.

With this exponential growth in costs, has come another key feature: a pervasive ‘winner takes all’ dynamic.

Quoting McKinsey:

The semiconductor industry’s record of steady technological improvement has created a winner-take-all dynamic that makes leading-edge capabilities vital within several segments. If a company’s product or service is even slightly better than a competitor’s, it typically captures an outsize portion—or even the vast majority—of industry revenue. This phenomenon is apparent along the entire value chain, from equipment production to chip manufacture.

Of course, we have seen this in semiconductor manufacturing where the ‘winner’ who has ‘taken all’ (in logic at least) is TSMC, and among the most recent ‘losers’ is Intel.

Intel Needs to Split

This brings us to Intel’s future. Or more specifically the future of Intel Foundry.

Most commentators now believe that Intel needs to split into separate product and foundry businesses. The rationale can be neatly summarised in two bullet points which cover why the current status quo isn’t satisfactory and why separating the Intel Foundry from Intel’s products is better:

Cashflow from the products business (essentially Intel CPUs) is no longer adequate to fund the development of the leading edge;

Common ownership gets in the way of Intel’s Foundry’s success, particularly in attracting the major customers that it needs.

For example, Ben Thompson’s position is clear:

To summarize, there is no market-based reason for Intel Foundry to exist; that’s not a market failure in a purely economic sense, but to the extent the U.S. national security apparatus sees it as a failure is the extent to which the U.S. is going to have to pay to make it happen. And, if the U.S. is going to pay up, that means giving that foundry the best possible chance to stand on its own two feet in the long run. That means actually earning business from Apple, Nvidia, AMD, and yes, even the fabless Intel company that will remain. The tech world has moved on from Intel; the only chance for U.S. leading edge manufacturing is to do the same.

“Intel” here means Intel in its current form.

We’ll have more to say about the disadvantages of Intel’s current IDM 2.0 strategy later. But what about the future of Intel Foundry as a separate business?

A recent post from Austin Lyons and Mark Rosenblatt sets out the case for further massive investment in Intel Foundry, starting with a national security imperative:

An American-owned, leading-edge semiconductor foundry is a strategic imperative for national security, particularly given emerging AI-driven warfare capabilities…

Replace AI-driven warface with missiles and we could be talking about Fairchild!

The only viable option for a US-owned leading-edge semiconductor foundry is Intel Foundry. In other words, Intel Foundry is too important to fail.

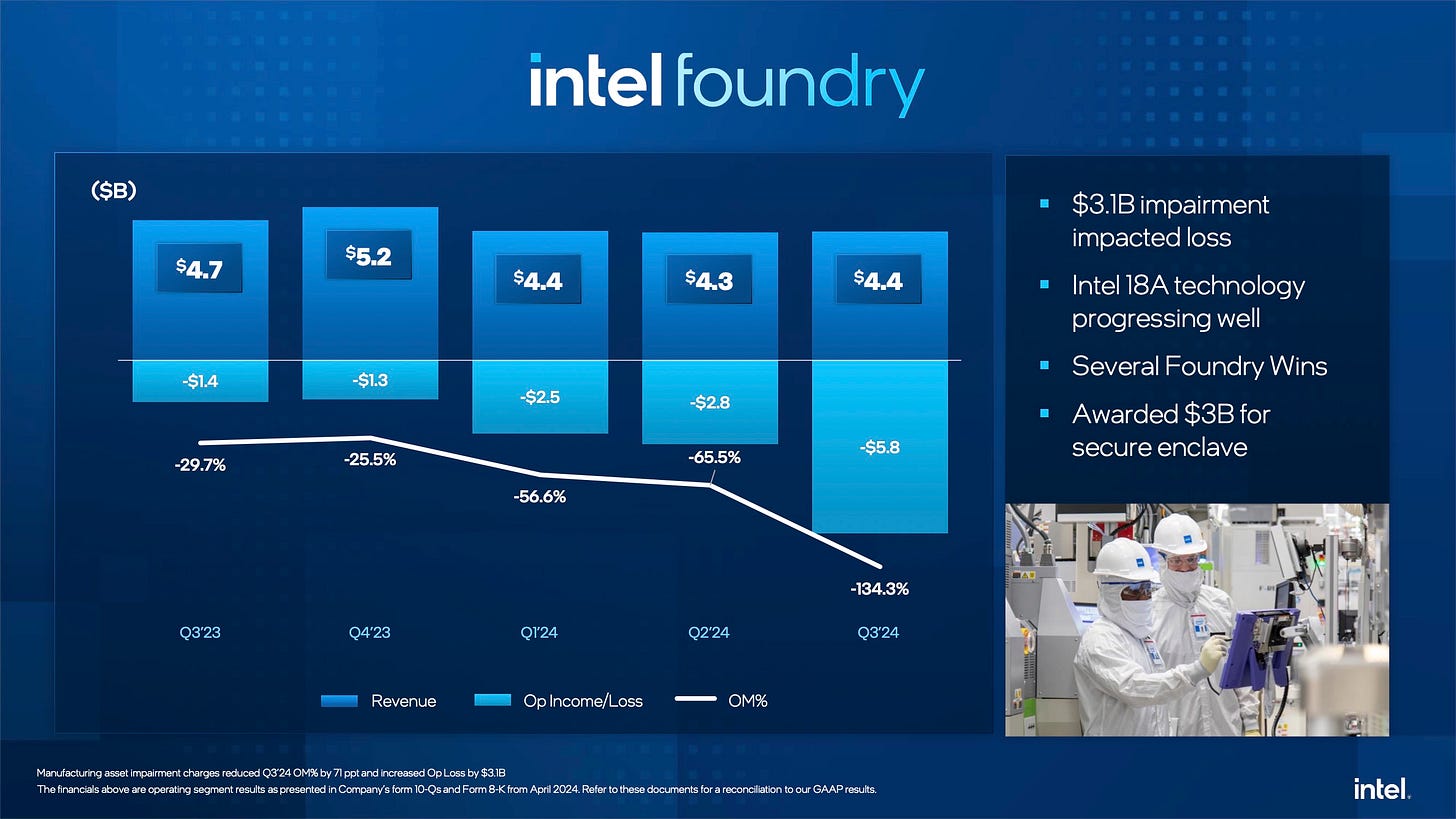

Austin and Mark then - convincingly in my view - make the case for Intel Foundry to be owned privately. Intel Foundry will make huge losses for the foreseeable future - it reported a loss of $5.8bn in the second quarter of 2024.

It also needs huge (greater than $100bn) further capital.

Public markets are unsuitable places for a business like this. And as Austin and Mark say, any private investment must be accompanied by massive additional government subsidies.

Back To The Future for Intel Foundry

Assuming these subsidies and investments are available, where does this take us?

More specifically does Intel Foundry have a viable future?

Let’s look back at Fairchild and Intel’s early days.

Fairchild was initially successful because of innovations like the NPN mesa transistor which were quickly turned into products that met the needs of major customers.

Fairchild’s early success was, in large part, built on government support through military contracts. But those military contracts were given to Fairchild not because it was the cheapest option - it didn’t have the scale to compete on price with rivals like Texas Instruments - but because it had technology that worked better for its customers and that technology had wide application.

Intel’s rapid growth in its early years was built on its innovation in SRAM, DRAM, microprocessors, EPROMs, and more. Crucially, early Intel didn’t just innovate; it worked hard to ensure this innovation made it to market into products that met the needs of its most deep-pocketed customers. Most importantly for Intel’s future, these included IBM with the 8088 microprocessor which made its way into the IBM PC.

So Fairchild and Intel’s success was built on innovation and customer focus. Today, scale is also essential for any firm that wants to compete as a leading-edge Foundry.

So what about the Intel of 2024?

Innovation

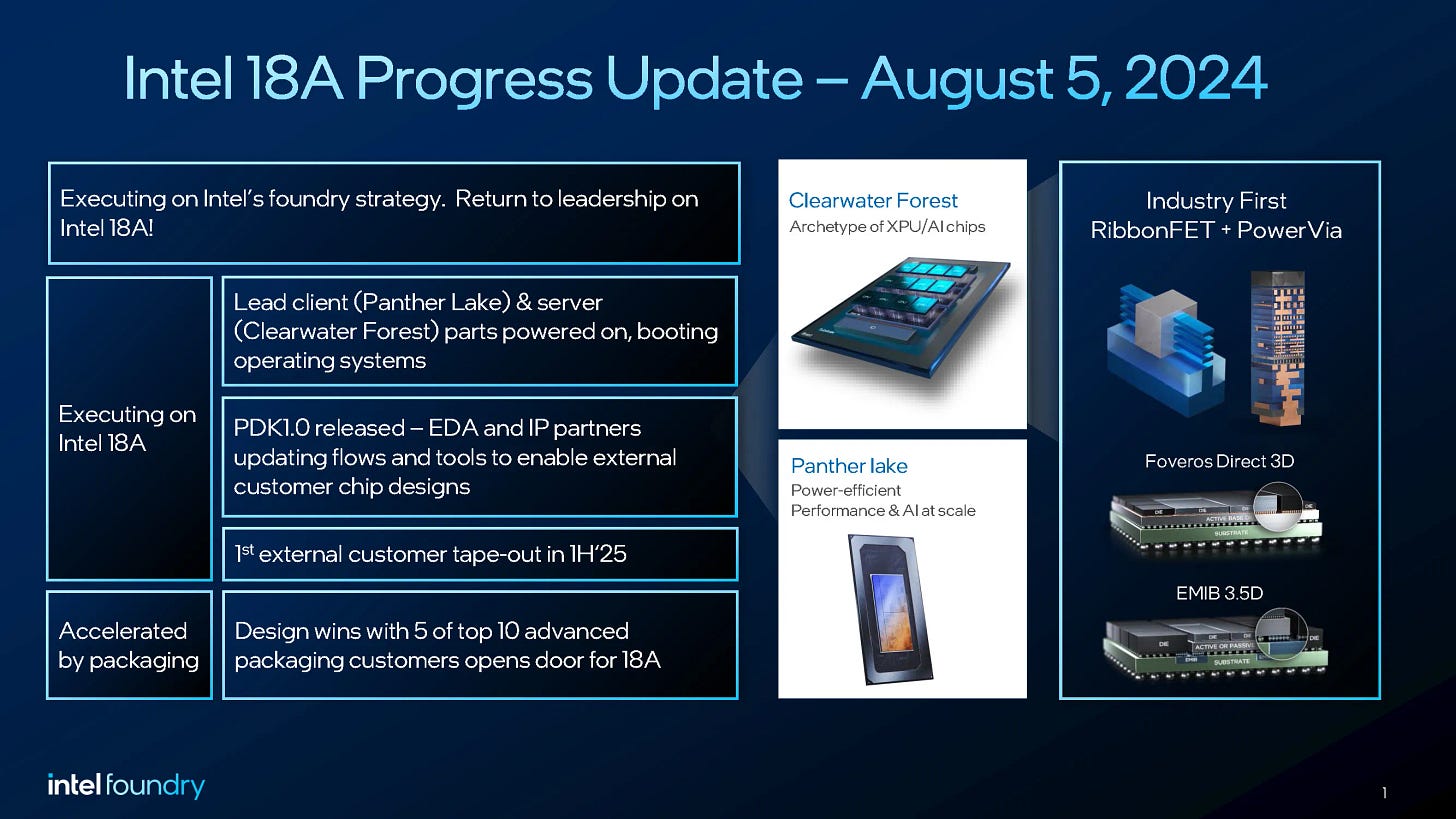

While there is plenty to criticize Pat Gelsinger for, Intel’s progress in developing ‘5 nodes in 4 years’, particularly on the Intel 18A process, has been impressive.

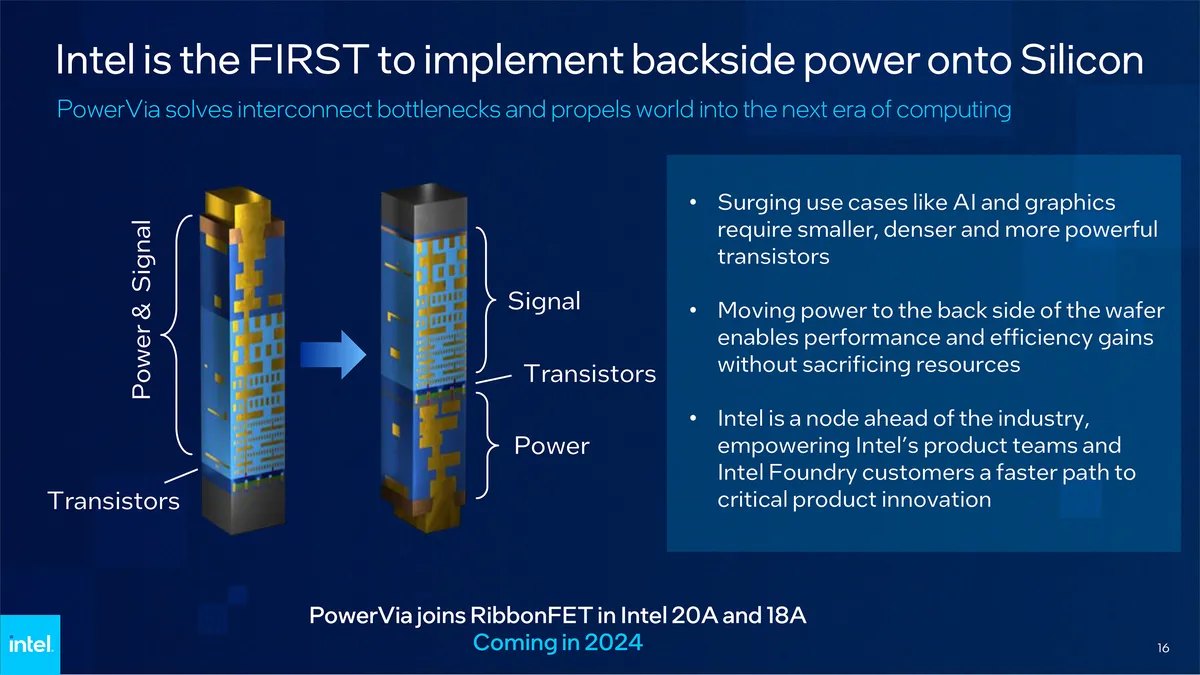

Alongside the node shrinks have been innovations such as backside power delivery.

From Tom’s Hardware:

Whether or not PowerVia BS PDN will be a tangible benefit is something only time will tell, but it is noteworthy that Intel is the first company that is ready to make chips with backside power delivery …

Volume production of A16 [TSMC’s first node with backside power delivery] will commence in the second half of 2026, giving Intel a clear lead.

Only time will tell if this is enough, particularly if 18A can enter volume production on schedule.

One thing is clear though: Intel Foundry can still innovate at the leading edge of semiconductor manufacturing.

Customer Focus

Is the Intel of 2024 focused on creating products to meet the needs of its customers?

Here, the answer has to be no. Intel has multiple products that - I don’t think it’s controversial to say - are products looking for customers, in markets where customers are already well served. These products include ARC Graphics and Gaudi AI accelerator products. Alongside draining financial resources from Intel Corporation, these products must inevitably be distractions, taking up management time and focus. They also compete with more successful products from potential Foundry customers.

Would anything significant change with a split into ‘Intel Foundry’ and ‘Intel Products’?

I think it would. Intel Foundry’s management would have a much clearer set of objectives: increasing the volumes of business passing through Intel Foundry’s Fabs. That means catering to the needs of a range of customers outside the current Intel, with much higher potential volumes than any of these products will ever deliver.

Crucially, Intel Foundry’s management would be rewarded solely based on the success of their business and not have those rewards tied to the results of the current Intel business.

Scale

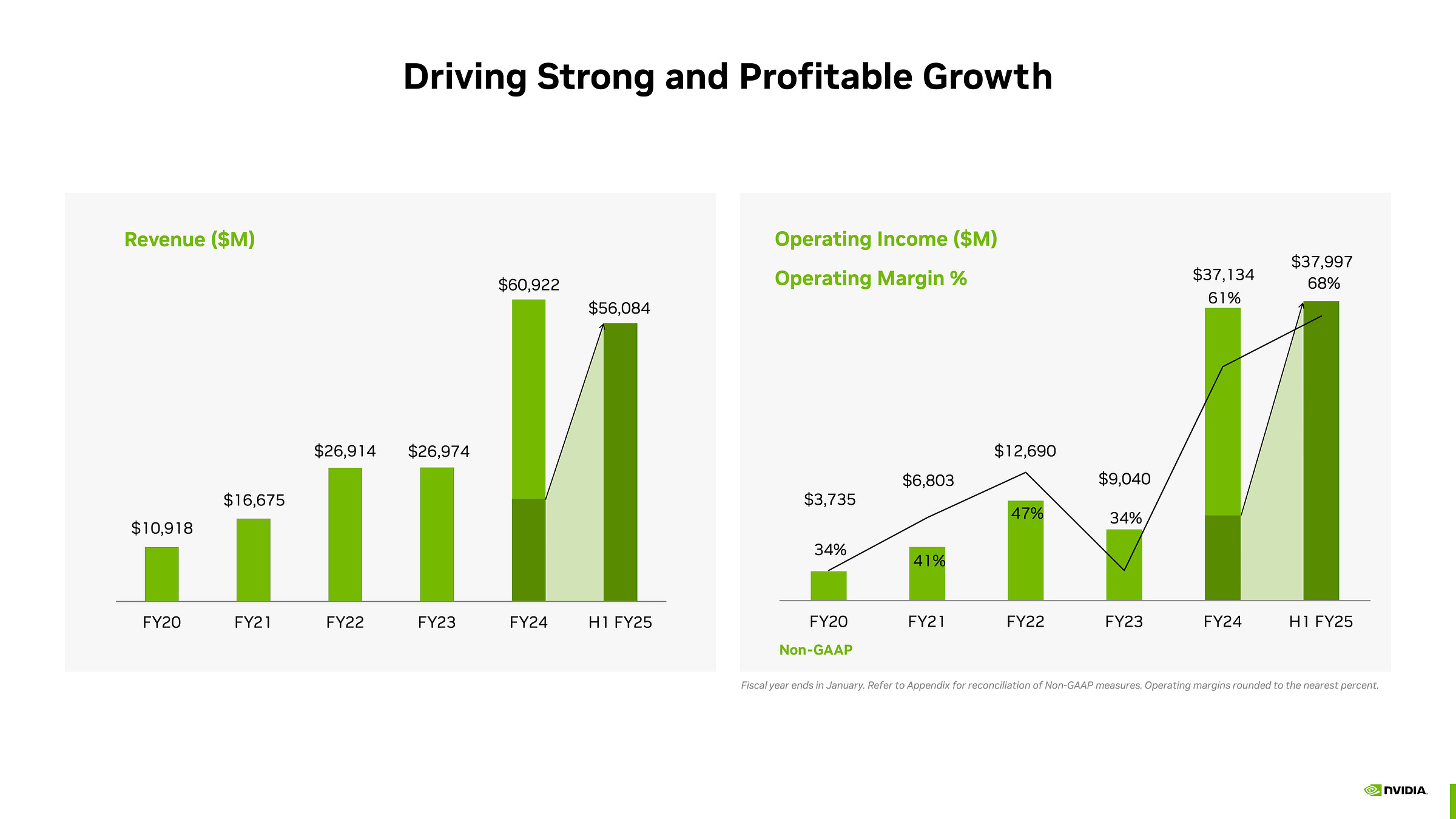

This takes us back to scale. The pace at which demand for leading-edge semiconductors is growing is remarkable. Nvidia alone has added over $70bn of annualized turnover over the last two years.

Of course, revenue is not the same as orders for its suppliers but the growth and the availability of cash to invest is undeniable.

I find it hard to believe that Nvidia, and many others with deep pockets, wouldn’t prefer to have competition and a choice of suppliers for their leading-edge logic chips.

Unshackled from Intel’s product division, Intel Foundry can truly focus on serving those customers. A few major customers using Intel Foundry, alongside orders from the now separate Intel Products business, create the scale that might give Intel Foundry a path to profitability and success.

Intel Foundry: A Positive Scenario

The pessimistic, and perhaps most prevalent, current view could be summarised as:

Intel Foundry lacks scale and a track record with external customers. It will continue to struggle to compete with TSMC. It fails to build significant market share and without scale fails to match TSMC on price.

If Intel was not innovating or there were no deep-pocketed customers who would like to see another leading-edge Foundry in competition with TSMC, then this might seem inevitable.

I’ll paint a more optimistic scenario though:

Intel delivers 18A on time. Potential customers see that 18A is, at a minimum, technically competitive and that there are clear business benefits in supporting an alternative to TSMC. Intel Foundry quickly attracts a number of major customers giving it a path to profitability.

This future depends on the successful delivery of 18A and more by Intel Foundry and political will, perhaps, above all else. But it does seem possible.

If Fairchild’s electronics were vital for Minuteman missiles in the 1960s then leading-edge semis are essential components in a huge range of military equipment and vital civilian infrastructure. The modern world runs on semiconductors.

Fairchild and Intel succeeded in the past by innovating and meeting the needs of their most important customers. Pat Gelsinger has talked about recapturing the ‘spirit of Andy Grove’. Just as important is the spirit of Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and the numerous others who drove innovation and customer focus at both firms in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

Disclaimer: This post puts forward a possible future for Intel’s Foundry business and not for Intel’s Corporation as a whole or for Intel’s stock price. The future of Intel and Intel Foundry depends on a wide range of factors that remain highly uncertain. This is not investment advice.