The Engine

Jonathan Swift (sort of) predicts Large Language Models in 1726

the most ignorant person, at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labour, might write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study.

Happy New Year to all Chip Letter readers!

Every year or so I like to look at an early event in the history of computing. We’ve previously discussed the roles of Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in the 1940s in the development of modern computing and AI. Going back a century we’ve also covered the friendship between Michael Faraday and Charles Babbage in the 1830s.

Today, we’ll go even further back in time to the 1720s and …

… possibly the earliest known reference to a device in any way resembling a modern computer.1

Remarkably this device anticipates ChatGPT and the other ‘Large Language Models’ that are dominating technology headlines three hundred years later.

The source of this reference? A book that was first published as:

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships.

Which is well known as Gulliver’s Travels, by the Anglo-Irish clergyman Jonathan Swift, first published in 1726.

Gulliver’s Travels is most famous for the first of its four parts, in which Gulliver Travels to Lilliput, an island populated by a race of people less than 6 inches (15cm) tall.

Some adaptations, especially those intended for children, end Gulliver’s travels with his return from Lilliput, which is understandable as the remaining travels lead to stories and encounters that are by turn threatening, bawdy, and downright disturbing.

In part 2 of the book, he travels to Brobdingnag (many of the locations and characters in the book have unpronounceable names) where he encounters a race of men around 72 (22 meters) feet tall. In part 4 he comes across a collection of deformed men (the Yahoos) and talking horses (the Houyhnhnms).

The reference to a ‘machine resembling a modern computer’ comes in part 3 of the book.

After being attacked by pirates, Gulliver finds himself on a barren island close to India. He is rescued by a flying island called ‘Laputa’ which hovers over him and allows him to ascend using a ladder.

Laputa hovers over the island of Balnibarbi with its capital city Lagado. Visiting the city Gulliver is shown around an organization called ‘The Grand Academy’.

At the Grand Academy of Lagado in Balnibarbi, great resources and manpower are employed on researching preposterous schemes such as extracting sunbeams from cucumbers, softening marble for use in pillows, learning how to mix paint by smell, and uncovering political conspiracies by examining the excrement of suspicious persons.

As a result of the investment in these ludicrous research projects, Lagado and the remainder of Balnibarbi have been reduced to abject poverty.

The Engine

Whilst at the Academy Gulliver encounters a machine called the ‘Engine’.

What is the Engine?

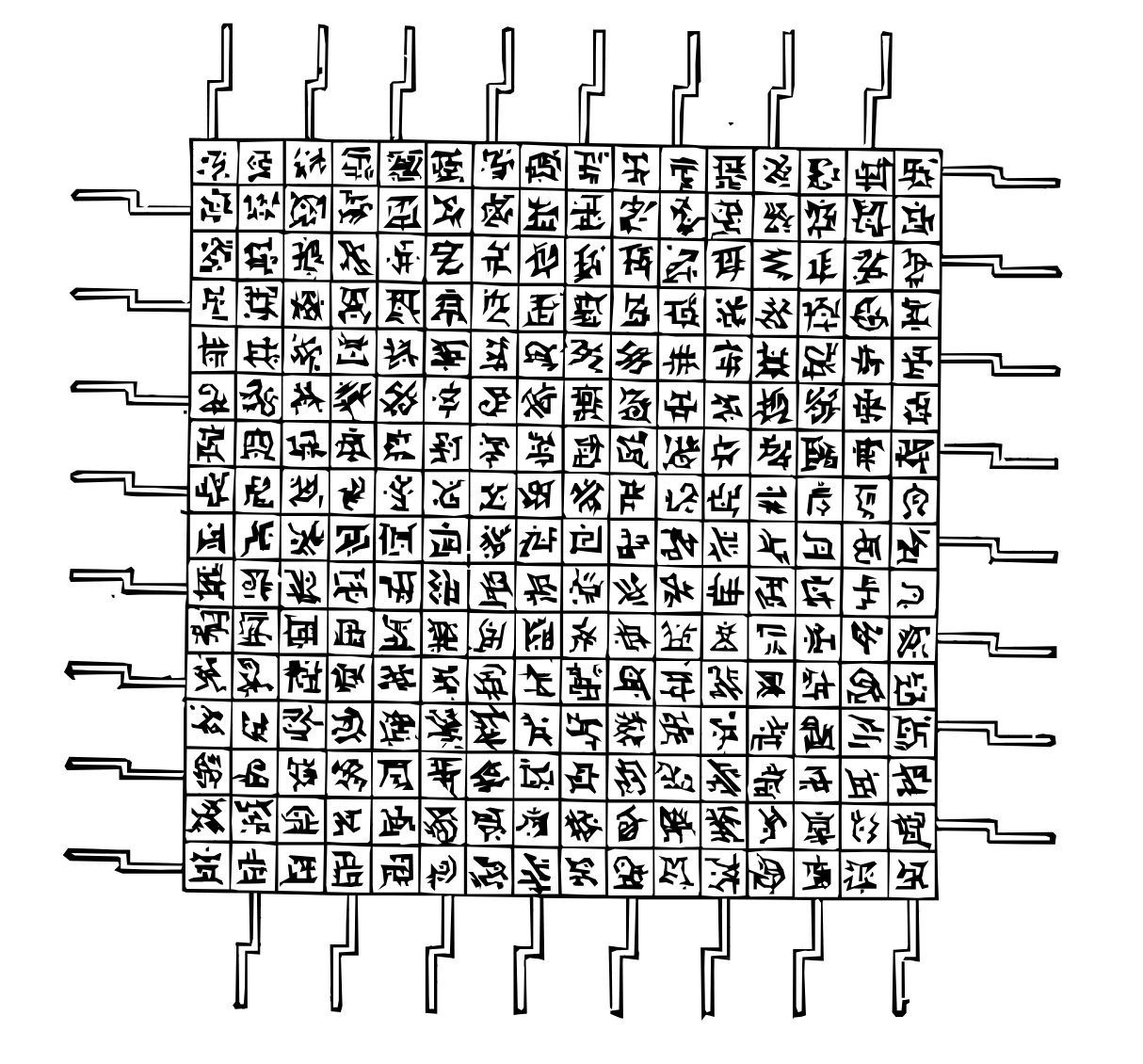

It was twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superfices was composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, but some larger than others.

They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered, on every square, with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language, in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order.

How does the Engine work?

The professor then desired me “to observe; for he was going to set his engine at work.” The pupils, at his command, took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame; and giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed.

And then the ‘lads’ set to work capturing the output from the machine:

He then commanded six-and-thirty of the lads, to read the several lines softly, as they appeared upon the frame; and where they found three or four words together that might make part of a sentence, they dictated to the four remaining boys, who were scribes.

This work was repeated three or four times, and at every turn, the engine was so contrived, that the words shifted into new places, as the square bits of wood moved upside down.

The professor and the lads have been busy capturing the output from the engine:

Six hours a day the young students were employed in this labour; and the professor showed me several volumes in large folio, already collected, of broken sentences, which he intended to piece together, and out of those rich materials, to give the world a complete body of all arts and sciences;

So we can see that the Engine is what we now call a Language Model.

The Professor even describes what we would today call his work to ‘train’ the Engine:

He assured me “that this invention had employed all his thoughts from his youth; that he had emptied the whole vocabulary into his frame, and made the strictest computation of the general proportion there is in books between the numbers of particles, nouns, and verbs, and other parts of speech.

So the Engine uses probabilistic techniques to generate its output, just as today’s Large Language Models do.

The 1727 edition of Gulliver’s Travels contains a picture of ‘The Engine’. And what does it resemble? An integrated circuit!

What is the purpose of the engine? The professor sees it as a way of making, for a modest charge, the ability to create books available to everyone:

Everyone knew how laborious the usual method is of attaining to arts and sciences; whereas, by his contrivance, the most ignorant person, at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labour, might write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study.

The Engine is to be made available as a mass-market product! Sounds familiar?

What’s more, like modern LLM builders ‘the professor’ is preoccupied with fund-raising:

Six hours a day the young students were employed in this labour; and the professor showed me several volumes in large folio, already collected, of broken sentences, which he intended to piece together, and out of those rich materials, to give the world a complete body of all arts and sciences; which, however, might be still improved, and much expedited, if the public would raise a fund for making and employing five hundred such frames in Lagado, and oblige the managers to contribute in common their several collections.

Understanding The Engine

What should we make of the Engine?

Chris Garcia at The Computer History Museum considered The Engine in an article more than a decade ago (well before ChatGPT) and concluded:

The Engine might be seen as a computer, but perhaps it’s better thought of as a sort of random-number generator.

Before going on to compare the Engine with Racter an early PC text generation program:

The program that could be seen as most similar to The Engine is Racter, a microprocessor-based program that could be used to randomly generate English poetry and prose. The original version of Racter was used to write a book of short prose and poetry called The Policeman’s Beard is Half Constructed. The creators claimed that it was the first book ever written by a computer. Some of the poetry was brief, such as “Slice a visage to create a visage. A puzzle to its owner,” while some of the prose stories ran for several pages. Like the Engine, Racter’s works were heavily edited down from a large amount of material, leading many to compare it to the theoretical “Monkeys with typewriters” concept.

So the Engine is a ‘monkeys with typewriters’ device that only eventually creates sensible sentences by pure chance.

However, I don’t think this does justice to Swift’s idea and his prescience.

If Swift had wanted to describe a ‘fully random’ device to generate text he could have done so. He could have explicitly stated that the Engine created a series of words from the letters of the alphabet using some randomizing mechanism.

But the Engine isn’t such a machine. It is much more complex than would be necessary to fulfill this. What’s more, the Professor has spent considerable time incorporating some of the workings of the English language into the operation of the machine. The engine is doing more than just choosing random letters.

The workings of the English language that are incorporated, as described by Swift, are very simplistic:

… of the general proportion there is in books between the numbers of particles, nouns, and verbs, and other parts of speech …

But that doesn’t detract from the principle. The Engine is being trained using the generality of the English books available to the professor.

It might be argued that, perhaps, the professor is completely deluded and that the Engine isn’t doing what he describes. Even after all the effort he has put into its design and his ‘training’, it is still producing random output. After all the other efforts of the Academy are completely ludicrous and the professors are quite foolish in believing they might succeed.

Once again though it is within Swift’s gift to describe this, but he chooses not to.

I think that it’s more likely that Swift intends to describe a machine that has been built to create English phrases in a manner that is more effective and efficient than a purely random device.

Of course, Swift can’t describe how it does this. But, hey, it’s 1726!

Modern LLMs and other generative AI isn’t perfect. LLMs are much better than the Engine but users still need to pick and choose the output and sometimes discard it.

The Engine in Context

The machine isn’t efficient, of course, and Swift regards it as a poor substitute for human efforts to expand human knowledge.

The Academy in Lagado itself is a satire on the Royal Society, the pre-eminent scientific research institution in London at the time, which was, at the time of the writing of Gulliver’s Travels, experiencing a difficult period. The futility of The Academy’s research efforts reflected Swift’s view of much of the activity at The Royal Society at the time. As part of that satire, the Engine probably reflects Swift’s view that some of the mechanical creations of members of The Royal Society were less than useful.

There is another perspective on Swift’s creation of the Engine. At the start of the 18th century engines of another type - steam engines - were starting to become widespread following Thomas Newcomen’s invention of his ‘atmospheric engine’.

Perhaps Swift saw the potential for these engines to replace manual labor.

If some jobs could be mechanized, why not Swift’s own as a writer?

It would be a prospect both ridiculous and terrifying, so it’s ideal material for inclusion in Gulliver’s Travels, a book full of the preposterous and scary.

So we have one final way in which Swift is remarkably prescient of 2025 and modern concerns about technology.

ChatGPT on The Engine

After considering Swift’s Engine, it was natural to ask ‘Altman’s Engine’ AKA ChatGPT what it knows about The Engine.

And then does ‘The Engine’ remind ChatGPT of itself?

The idea of the Lagado engine humorously critiques the notion of reducing creativity to mechanics, yet modern Al, like ChatGPT, demonstrates that meaningful, contextually appropriate text can indeed emerge from algorithmic processes. Swift likely never imagined that his satire might one day resemble actual technology!

For more on Gulliver’s Travels David Runciman on the Past Present Future podcast is terrific (and this episode had only 2 views on YouTube at the time of writing - it deserves many more).

Gulliver’s Travels can be read for free (or downloaded to your e-reader) here at Standard E-Books.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Engine

I’m actually quite staggered by how prescient this is!

Swift's engine was probably a parody of earlier ideas about mechanical aids to human thinking, i.e., "artificial intelligence." See here https://www.forbes.com/sites/gilpress/2022/10/30/history-of-ai-in-33-breakthroughs-the-first-thinking-machine/